DE BELLO JUDAICO

LIBER SEPTIMUS |

THE JEWISH WAR

BOOK SEVEN |

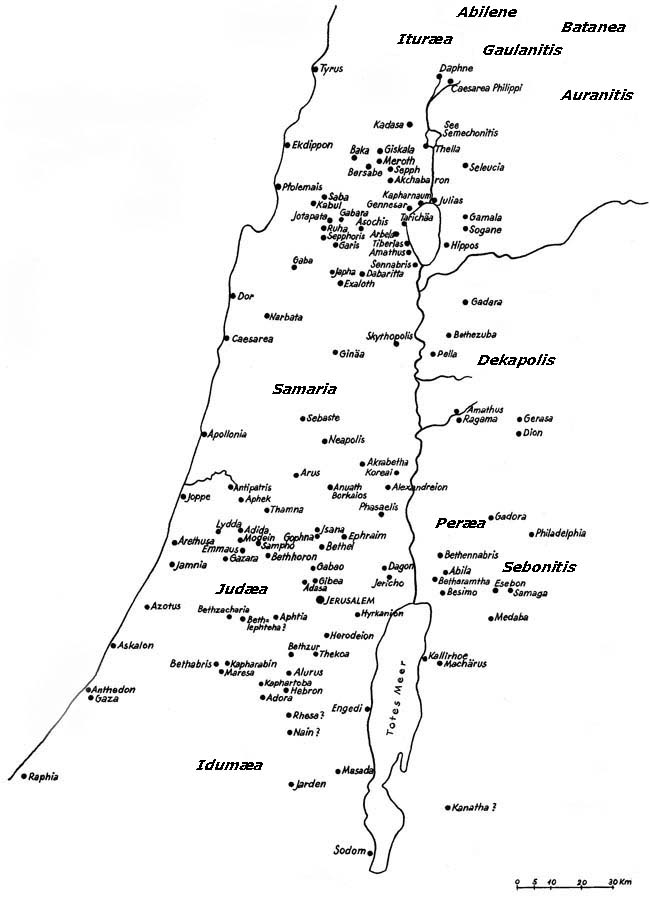

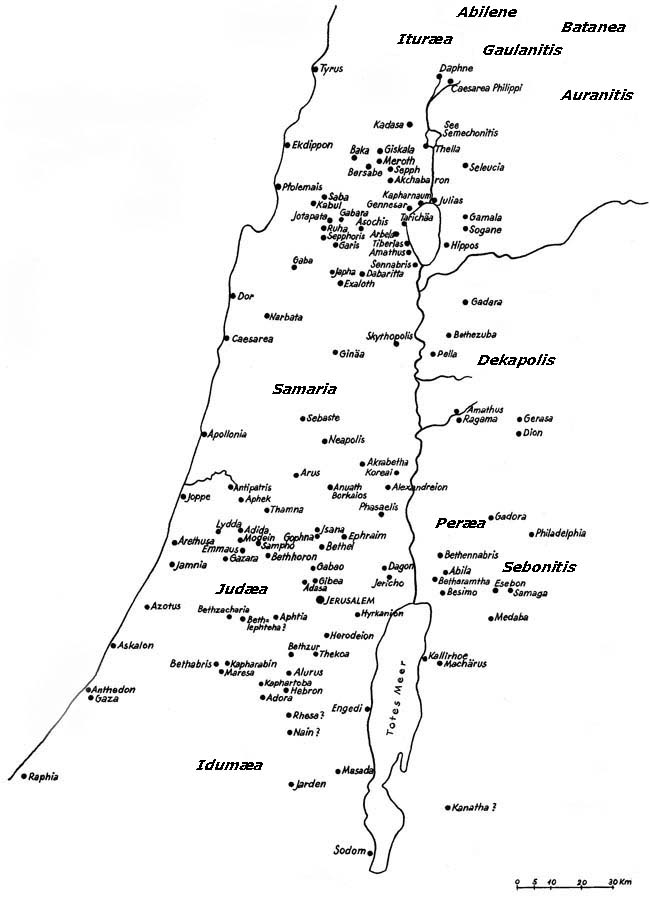

Palæstina

with locations mentioned by Josephus

|

|

| Book 7 |

| From the Taking of Jerusalem by Titus to the Sedition of the Jews at Cyrene. |

|

| ⇑ § I |

| Quomodo tota Hierosolymorum urbs plane diruta est præter tres turres : utque Titus in contione extollit milites, et præmia illis distribuit, multosque dimittit. | How the Entire City of Jerusalem Was Demolished, Excepting Three Towers ; and How Titus Commended His Soldiers in a Speech Made to Them, and Distributed Rewards to Them and Then Dismissed Many of Them. |

| 1 |

| POSTQUAM vero quos occideret quidve raperet, non habebat exercitus, quod iratis animis omnia deerant (nec enim parcendo si esset quod agerent, abstinuissent), jubet eos Cæsar totam funditus jam eruere civitatem ac templum : relictis quidem turribus, quæ præter alias eminebant, Phasaëlo, et Hippico, et Mariamne, murique tanto, quantum civitatem ab Occidente cingebat — id quidem, ut esset castrum illic custodiæ causa relinquendis : turres autem, ut posteris indicarent qualem civitatem, quamve munitissimam, Romanorum virtus obtinuisset. |

After the army did not have anyone to kill or anything to plunder, because everything was lacking for their enraged emotions (since indeed they would not have abstained by sparing anything if it there were something to go after), Cæsar ordered them to destroy completely the City and the Temple, leaving just the towers which stood higher than the others, Phasaël, and Hippicus, et Mariamne, and as much of the wall that surrounded the City on the west — which he ordered so that for the sake of the garrison there would be a camp for those to be left there; and the towers so that they would show posterity what kind of or how greatly fortified a City the valor of the Romans had conquered. |

| Alium vero totum ambitum civitatis ita complanavere diruentes, ut qui ad eam accessissent, habitatam aliquando esse vix crederent. Hic quidem finis eorum dementia, qui novas res movere temptaverunt, Hierosolymis fuit, clarissimæ civitati, et apud omnes homines prædicatissimæ. |

Demolishing it, they leveled the other whole perimeter of the City to the point that whoever came there would hardly believe it ever to have been inhabited. This, as a result of the madness of those who attempted to bring about a revolution, was indeed the end for Jerusalem, a most famous city and one greatly praised among all men. |

| 2 |

— Caput G-19 —

De præmio militum. |

| Cæsar autem præsidio quidem illic statuit relinquere Decimam Legionem, nonnullasque alas equitum, ac peditum cohortes. Omnibus autem belli partibus administratis, et laudare universum cupiebat exercitum pro rebus fortiter gestis, et debita viris fortibus præmia persolvere. |

But Cæsar decided to leave there the Tenth Legion and a few squadrons of cavalry and cohorts of infantry. Then having administered all the issues of war, he wished to praise the entire army for its valiantly accomplished deeds and give out rewards to his brave men. |

| Composito autem in medio ante castra magno tribunali, stans in eo cum procĕrum eminentissimis, unde ab omni milite posset audiri, magnam illis ait habere se gratiam, quod benevolentia erga se utendo perseverassent. |

After placing in the center in front of the camp a large stage, standing on it with the most distinguished of his officers where he could be heard by all the soldiers, he said he was greatly thankful to them for having persevered in showing their goodwill toward him. |

| Laudabat autem, quod per omnia bella morigeri fuissent, quodque prœliando fortitudinem in multis magnisque periculis monstrassent, patriæ per se amplificantes imperium : omnibusque planum facientes hominibus, quia neque hostium multitudo, neque munitiones regionum, neque magnitudines civitatum, vel audacia inconsulta, et immanitates efferæ adversantium, possint unquam Romaorum vires vel manus effugere, quamvis in multis rebus aliqui fortunam opitulantem habuerint. |

He next praised the fact that they had been compliant throughout the entire war, and that they had shown strength in fighting in many and great dangers — by themselves increasing the power of the fatherland, and making it clear to all men that neither the numbers of the enemy nor the fortifications of the locations nor the size of the cities or thoughtless audacity and the wild savagery of the adversaries could ever escape the power and grip of the Romans, even though in many cases some might have luck in their favor. |

| Pulchrum quidem esse, ait, illos etiam bello finem imponere, quod multo tempore gestum sit. Nec enim optasse his quicquam melius, quum id ingrederentur. Hōc autem pulchrius atque præclarius, quod duces Romani et administratores imperii, ab his declaratos ac præmissos in imperium, cuncti libenter suscipiunt : et his quæ ipsi decrevere, standum putant, agentes his gratias, qui legissent. |

It was indeed beautiful, he said, that they had put an end to a war that had been waged for a long time. For he had not wished anything greater for them when they entered upon it. More beautiful and excellent than that was the fact that all gladly accepted the leaders and administrators of the Roman Empire who had been declared and sent ahead to the throne by them, and that, thanking those who had made that choice, they all thought that there should be acquiescence to the things which they had decreed. |

| Mirari autem se eos ac diligere omnes, quia nemo viribus alacritatem habuit tardiorem. Et illis tamen, qui pro majore vi clarius decertassent, vitamque suam condecorassent fortibus factis, et re bene gesta militiam suam nobiliorem fecissent, dixit se et honores et præmia redditurum : nec ullum eorum, qui plus alio laborare voluisset, justa vicissitudine cariturum magnamque sibi hujus rei fore diligentiam, quod magis vellet honorare virtutes eorum qui militiæ socii fuissent, quam punire peccata. |

But he marveled at them and loved them all, because no one had an eagerness slacker than his strength. And nonetheless, he said, to those who, in line with their greater strength had fought more brilliantly and had distinguished their lives with brave deeds, and through well performed exploits had made his forces more famous, he was going to give both honors and rewards, and that none of those who had wanted to struggle more than others would be without his just recompense; and that that would be a primary concern of his in this matter, because he preferred honoring the valor of those who had been his comrades in arms to punishing any failings. |

| 3 |

| Confestim ergo jussit eos quorum partes sunt, indicare, quosnam scirent fortiter aliquid in bello fecisse : et nominatim singulos appellans, præsentes collaudabat, quasi qui domesticis recte gestis nimium lætaretur : et coronas eis aureas imponebat, et torques longasque hastas, et signa ex argento facta donabat, et uniuscujusque ordinem mutabat in melius. Quin et ex manubiis aurum et argentum, itemque vestes, aliamque prædam largiter distribuebat. |

He therefore immediately ordered those under whom the sections were to point out those they knew had accomplished something valiantly in the war; and addressing the individual men by name, he praised them highly in their presence, like a man who was extravagantly rejoicing over his family’s properly performed deeds; and he placed gold crowns on them and awarded necklaces and long spears and standards made of silver, and changed the rank of each one to a higher one. Moreover from the spoils he lavishly distributed both gold and silver, and likewise garments and other booty. |

| Omnibus autem ita donatis, ut quisque se meritum præbuerat, votisque cum universo exercitu factis, magno favore descendit vertitque se ad sacra pro victoria celebranda : magnaque astante boum multitudine circum aras, immolatos omnes exercitui dedit ad epulas, ipse vero cum honoratis per triduum lætatus, milites quidem alios quo quenque conveniret, dimittit. |

After everyone had been thus rewarded in accordance with how each one had showed himself deserving, and having offered prayers with the entire army, amidst great applause he descended and turned to celebrating the rites for the victory. With a great number of cattle standing around the altars, after sacrificing them all he gave them to the army for a banquet. He himself, after celebrating with his officers for three days, discharged the other soldiers to where it suited each unit. |

| Hierosolymorum autem custodiam Decimæ Legioni credidit : neque ad Euphratem, ubi pridem fuerat, eam remisit. Duodecimam vero Legionem, memor quod Cestio duce Judæis cesserat, totam Syria pepulit : erat enim olim apud Raphanæas : ad Meliten autem, quæ sic vocatur, misit : hæc ad Euphratem in confinio Armeniæ et Cappadociæ sita est. |

He next entrusted the guarding of Jerusalem to the Tenth Legion and did not send it back to the Euphrates where it had formerly been. But the Twelfth Legion, remembering that under the leadership of Cestius it had given way to the Jews, he drove out of all of Syria (for it was once at Raphaneai); instead, he sent it to the so-called Melitene; this is located on the Euphrates on the borders of Armenia and Cappadocia. |

| Duas vero sibi obsequi satis esse duxit, donec ad Ægyptum perveniret, Quintam et Quintamdecimam Legiones. Deinde quum ad maritimam Cæsaream cum exercitu descendisset, in eam manubiarum multitudinem reposuit, captivosque ibi asservari præcepit, quod ad Italiam navigare tempus hiemis prohibebat. |

But he considered it sufficient for two legions — the Fifth and the Fifteenth — to follow him until he arrived in Egypt. Finally, when he had gotten down with the army to Maritime Cæsarea, he stored in it the mass of spoils and ordered the captives to be guarded there because the wintertime prevented sailing to Italy. |

|

| ⇑ § II |

Quomodo Titus Cæsareæ Philippi varia edit spectacula.

De Simone tyranno, quo modo captus erat et triumpho servatus. | How Titus Exhibited All Sorts of Shows at Cæsarea Philippi. Concerning Simon the Tyrant, How he Was Taken and Reserved for the Triumph. |

| 1 |

— Caput G-20 —

De navigatione Vespasiani, deque comprehenso Simone et spectaculo die natalicio exhibito. |

| PER idem vero tempus, quo Titus Cæsar obsidionis causa apud Hierosolymam commorabatur, ascensa navi oneraria Vespasianus Rhodum transmittit. Hinc autem vectus triremibus, postquam omnes quas præternavigavit civitates invisit, ab his cum votis exceptus, in Græciam ex Ïonia transit. Egressus deinde Corcyra in Ïapygiam delatus est, unde jam terra iter agebat. |

But during the same time when Cæsar Titus was staying at Jerusalem because of the siege, Vespasian, boarding af freight ship, crossed over to Rhodes. Then traveling from here via a trireme, after he visited all the cities he sailed past, having been received by them with congratulations, he crossed from Ionia to Greece. Finally, leaving from Corcyra, he was taken to Iapygia, whence he made the journey by land. |

| Titus autem ex maritima Cæsarea reversus in Cæsaream, quæ Philippi vocatur, advenit, diuque ibi commorabatur, celebrans omnia genera spectaculorum : multique in ea captivi consumpti sunt, alii bestiis objecti, alii autem catervatim more hostium inter se depugnare coacti. Hic Simonem etiam Gioræ filium comperit, hoc modo comprehensum. |

On the other hand, Titus, returning from Maritime Cæsarea, arrived in the Cæsarea called Philippi, and stayed there for quite a while, celebrating all kinds of shows; in it, many captives perished — some thrown to the beasts, but others in groups, forced like enemies to fight against one another. Here he learned that Simon, the son of Gioras, had been captured in the following way. |

| 2 |

| Iste Simon, quum Hierosolyma obsideretur in superiore civitate constitutus, postquam muros ingressus exercitus totam vastare civitatem cœperat, tunc fidelissimis amicorum ascitis, et lapidariis cum ferramentis eorum necessitati congruis, et alimentis quæ multis diebus sufficere possent, una cum illis omnibus in quandam occultiorem cloacam sese demittit. |

This Simon, located in the upper City when Jerusalem was being besieged, after the army, entering, had begun to lay waste to the entire City, then gathering his most loyal friends and stone masons with the tools appropriate for their needs and food which could suffice for many days, climbed down together with all of them into a certain more hidden sewer. |

| Et quoad fossa patebat, illi progrediebantur : ubi vero soliditas obstitisset, eam suffodiebant, sperantes posse ulterius progressos tuto emergere, atque ita servari. Sed hanc exspectationem veram non esse, rei periculum refellebat. Vix enim paululum fossores processerant, jamque alimenta, quamvis parce his uterentur, eos deficiebant. |

And they continued as far as the excavation was open. But where solid earth blocked them, they dug under it, hoping to be able, having advanced, to emerge safely and thus be saved. But the effort of the matter disproved this hope as not being correct. For the diggers had hardly progressed a little when the food, even though they were using it sparingly, ran out on them. |

| Tunc igitur velut stupore posset Romanos fallere, albis tunicis, innexaque fibula, ac chlamyde purpurea indutus, illo in loco ex terra editus ubi templum antea fuerat, apparuit. Ac primo quidem obstupuere, qui eum viderunt, locisque suis manebant, deinde propius quum accessissent, quis esset, percontati sunt. Et id quidem Simon non dicebat. |

So then, as though to deceive the Romans with shock, having donned white tunics and pinned with a broach, plus a crimson cloak, he appeared emerging from the earth on the spot where the Temple had formerely been. And those who first saw him were dumbfounded and stayed in their places; then when they had approached him more closely, they inquired as to who he was. Simon, as it happened, did not tell them that. |

| Jubebat autem ad se ducem vocari ; statimque accersitus ab his, qui ad eum cucurrerant, venit Terentius Rufus : namque is rector militiæ relictus erat. Omni autem ab eo veritate comperta, ipsum quidem vinctum custodiebat : Cæsari vero quemadmodum esset comprehensus, indicavit. |

Rather, he ordered them to have their leader called to him; and Terentius Rufus, having been immediately summoned by those who had run to him, came. For Rufus had been left as the leader of the troops. After the whole truth had been learned by him, he put him under guard in chains, then reported to Cæsar how he had been taken into custody. |

| Simonem quidem in ultionem crudelitatis, qua in cives suos amarē ac tyrannice fuerat usus, in potestate hostium quibus maxime invisus erat, ita Deus posuit, non vi subditum eorum manibus, sed sua sponte ad supplicium adductum : propterea quod plurimos ipse crudeliter interemerat falsis criminationibus insimulatos, defectionis scilicet ad Romanos. |

Thus indeed God placed Simon, as punishment for the cruelty that he bitterly and tyrannically practiced on his own citizens, into the power of enemies to whom he was intensely detestable — not subjected by the force of their hands, but delivered of his own accord to execution, because he had cruelly killed a great many accused on false charges — specifically, of defection to the Romans. |

| Nec enim potest iram Dei effugere nequitia, nec invalida res est justitia ; sed quandoque sui temeratores ulciscitur, et graviorem pœnam ingerit criminosis, quum jam se liberatos esse crediderint, eo quod non statim luere commissa. Id etiam Simon didicit, postquam in iras Romanorum incidit. |

And evil cannot escape the wrath of God, nor is justice something weak; rather, it eventually takes vengeance on its transgessors and inflicts a punishment all the graver when they think themselves to have been freed because they have not immediately paid for their crimes. Simon too learned that after he fell into the wrath of the Romans. |

| Illius autem ascensus e terra, magnam etiam aliorum seditiosorum multitudinem eisdem diebus fecit in cloacis deprehendi. Cæsari autem maritimam Cæsaream reverso, vinctus Simon oblatus est. Et illum quidem triumpho, quem Romæ acturus erat, servari jussit. |

But the emergence of that man from the earth also caused a large number of other insurgents to be caught in the same sewers. Moreover after Cæsar had returned to Maritime Cæsarea, Simon, in chains, was presented to him. And he ordered him kept for the triumphal procession which he was going to celebrate in Rome. |

| 3 |

|

| ⇑ § III |

Quomodo Titus,

quum diem natalem fratris patrisque celebraret,

multos Judæorum consumpsit.

De Judæis in periculum apud Antiochiam adductis

ex Antiochi Judæi iniqua legum violatione. | How Titus upon the Celebration of his Brother’s and Father’s Birthdays Had Many of the Jews Slain. Concerning the Danger the Jews Were in at Antioch, by Means of the Transgression and Impiety of one Antiochus, a Jew. |

| 1 |

| IBI autem moratus, fratris sui natalem diem clarissime celebrabat, multam partem damnatorum ejus honori attribuens. Numerus enim eorum, qui cum bestiis depugnarunt, quique ignibus cremati sunt, et inter se digladiatores periere, duo milia quingentos excessit. Omnia tamen Romanis videbantur hæc — licet mille modis illi consumerentur — minus esse supplicii. |

But while staying there, he celebrated his brother’s birthday splendidly, devoting a large part of the condemned to his honor. For the number of those who fought with beasts and who were consumed with fire and perished as gladiators against one another exceeded two thousand five hundred. Nonetheless — even though they were destroyed in a thousand ways — all these things seemed to the Romans to be too little a punishment. |

| Postea Cæsar Berytum venit (hæc autem est civitas Phœnices provinciæ, colonia Romanorum) et in hac quoque diutius demoratus est, majore usus claritudine circa natalem patris diem, tam magnificentia spectaculorum, quam sumptibus aliis excogitatis, quum etiam captivorum multitudo eodem quo antea modo periret. |

After this Cæsar came to Beirut (this is a Roman colony, a city of the province of Phœnicia) and stayed for a longer time in it too, employing yet greater pomp around his father’s birthday, both in the magnificence of the shows and in other ingenious luxuries, while a mass of captives likewise perished in the same way as formerly. |

| 2 |

— Caput G-21 —

De calamitate Judæorum apud Antiochenses. |

| Evenit autem per idem tempus, Judæos qui apud Antiochiam reliqui erant, acerba et exitiosa pericula perpeti, concitata in eos Antiochensium civitate, tam propter criminationes illatas eis in præsentia, quam propter ea quæ fuerant non multo ante commissa. De quibus necessarium mihi videtur pauca prædicere, ut etiam quæ postea gesta sunt, consequenti narratione referamus. |

Moreover at the same time it happened that the Jews who were left at Antioch experienced bitter and deadly dangers due to the city of Antioch being roused against them both on account of accusations currently brought against them as well as because of things which had been committed not much earlier. It seems necessary for me to say a few things about them so that in the subsequent narrative we can also relate what happened afterward. |

| 3 |

| Judæorum namque gens multum quidem totius orbis indigenis asseminata est. Plurimum autem Syris vicinitate permixta, præcipue apud Antiochiam versabatur, propter magnitudinem civitatis, maxime vero his liberam domicilii facultatem reges, qui post Antiochum fuerant, præbuerunt. Namque Antiochus quidem, qui Epiphanes dictus est, vastatis Hierosolymis templum spoliavit. |

For the people of the Jews is greatly seeded among the inhabitants of the entire world. Above all being mixed in with the Syrians due to proximity, it is found especially at Antioch on account of the size of the city, but particularly because the kings who came after Antiochus granted them free permission of residence. For indeed Antiochus, who was called Epiphanes, after laying waste to Jerusalem, plundered the Temple. |

| Qui vero post eum regnum assecuti sunt, quicquid aēneum in donariis fuit, hoc Judæis apud Antiochiam degentibus reddidere, in eorum synagoga dedicatum : concesseruntque, ut pari cum Græcis jure civitatis uterentur. A secutis quoque postea regibus eodem modo tractati, et multitudine profecere, et exstructione, itemque magnificentia munerum templum clarius reddidere : semperque religione sibi sociantes magnum paganorum multitudinem, etiam illos quodammodo sui partem fecere. |

But those who acquired the kingship after him gave whatever in bronze was among the donations back to the Jews living in Antioch, it being dedicated to their synagogue; and they allowed them to enjoy equal citizenship rights with the Greeks. Also treated afterwards by the following kings in the same way, they advanced both in numbers and in construction, and likewise with the magnificence of the gifts rendered their temple more splendid; and in their religion constantly gaining a large multitude of pagans, they even made them a kind of part of themselves. |

| Quo tempore autem bellum fuerat conclamatum, et recens in Syriam Vespasianus delatus est navigio, Judæorum vero odium apud omnes pullulabat, tunc unus eorum Antiochus quidam plurimum patris causa honorabilis (erat enim princeps apud Antiochiam Judæorum), quum Antiochensium populus contionaretur in theatro, progressus in medium, patrem suum et ceteros deferebat, insimulans eos, quod una nocte totam civitatem incendere statuissent : et velut hujus consilii participes quosdam hospites Judæos tradidit. |

Now at the time when the war had been declared and Vespasian had recently arrived in Syria by ship, and moreover a hatred for Jews was brewing among everyone, one of them, a certain Antiochus, especially distinguished because of his father (for he was a chief of the Jews in Antioch), when the Antiochene populace was assembled in the amphitheater, he, proceeding into the center, accused his own father and others, charging that they had decided to burn down the entire city in a single night; and he handed over some visiting Jews as participants in this plot. |

| His autem auditis, populus iram cohibere non poterat : sed in eos quidem, qui traditi fuerant, ignem jussit afferri : statimque omnes in theatro concremati sunt. In multitudinem vero Judæorum properabat irruere, si eos celeriter ulti essent, patriam suam servatum iri existimantes. |

Having heard this, the populace could not restrain its rage, but ordered that those who had been handed over be consigned to flames, and immediately they were all burnt to death in the amphitheater. Next they rushed to charge against the mass of the Jews, thinking that if they swiftly avenged themselves against them, their fatherland would be saved. |

| Antiochus autem iracundiam magis accendere, mutatæ voluntatis argumentum, quodque Judæorum mores odisset, exhibere se credens, si paganorum ritu sacrificaret, idemque jussit et ceteros compelli facere : renuendo enim manifestos insidiatores fore. Hujus autem rei periculo ab Antiochensibus facto, pauci quidem consenserunt : alii vero qui noluerunt, perempti sunt. |

Moreover Antiochus enflamed their anger yet more, thinking he would show the proof of his changed attitude, and that he hated the customs of the Jews, if he sacrificed in the manner of the pagans; and he ordered the others to be compelled to do the same as well, for, by refusing, the insurgents would be revealed. When the experiment of this matter was then made by the Antiochenes, few indeed complied; but those others who would not do so were slain. |

| Antiochus autem acceptis a Romanorum duce militibus, sævius instabat suis civibus, nequaquam eos die septimo ab opere cessare permittens, sed omnia cogens facere, quæ diebus aliis agerent. Tamque validam necessitatem imposuit, ut non modo apud Antiochiam septimi diei feriæ solverentur, sed ab hoc exordio in ceteris quoque civitatibus ad breve similiter tempus fieret. |

Moreover, receiving soldiers from the leader of the Romans, Antiochus went after his own fellow citizens savagely, not allowing them to desist at all from work on the seventh day, but forcing them to do everything that they did on other days. And he imposed such a harsh compulsion, that the sabbatical of the seventh day was abolished not only at Antioch but, from this beginning, it also took place for a short time similarly in the other cities. |

| 4 |

| Judæis autem apud Antiochiam tunc ejusmodi mala perpessis, altera denuo calamitas accidit : de qua narrare conati, hæc quoque persecuti fuimus. |

Now after the Jews had suffered problems of this kind, once again another calamity struck — in trying to give an account of which we have described these things as well. |

| Namque quod quadratum forum exuri contigit, et archiva monumentorumque receptacula publicorum, itemque basilicas; vixque ignis inhibitus est super omnem civitatem magna nimis vi ruens; hujus facti Antiochus Judæos accusat : et Antiochenses, quod scilicet si his infesti antea non fuissent, recenti tamen ex incendii tumultu facile calumnia perpulisset, multo magis ex anteactis fidem habere dictis suis persuasit, ut pæne se vidisse ignem a Judæis injici arbitrarentur : et tanquam furore correpti, magno cum ardore cuncti adversus eos, qui accusabantur, impetus facerent. |

For it happened that the Square Marketplace was burnt down and the archives and the depository of public deeds, and likewise the malls. And the fire, roaring over the entire city with enormous force, was barely contained. Antiochus accused the Jews of this deed. And because indeed even if they had not previously been hostile to the Jews, nonetheless with the current commotion over the fire, through a lie he could easily have compelled the Antiochenes, given the previous actions he all the more convinced them to give credence to his words, so that they almost thought that they themselves had seen the firebrands being thrown in by the Jews. And as though seized by madness, with great furor they all made attacks on those who were being accused. |

| Vix autem motus eorum potuit reprimere Collega adhuc juvenis legatus, postulans sibi permitti referre ad Cæsarem gesta. Rectorem namque Syriæ Cæsennium Pætum jam quidem Vespasianus ad eam miserat, nondum autem ille pervenerat. Habita vero diligenti quæstione, Collega repperit veritatem. Et eorum quidem Judæorum quos Antiochus accusaverat, nemo conscius fuit. |

The still young legate, Collega, could barely stop their upheavals, demanding that it be permitted him to refer the happenings to Cæsar. For Vespasian had already send Cæsennius Pætus to Syria as governor, though he had not yet arrived. But by holding a careful investigation, Collega discovered the truth. And indeed of those Jews whom Antiochus had accused, none was guilty. |

| Omne autem facinus admisere homines quidam nocentissimi necessitate debitorum, rati quod si forum et scripta publica concremassent, exactione liberarentur. Judæi quidem pro suspensis criminationibus futura exspectantes, magno timore fluctuabant. |

Rather, some very wicked men admitted the entire crime due to the pressure of their debts, thinking that if they burned down the marketplace and the public records they would be freed of the claims on them. The Jews, concerned about the future due to the suspended accusations, hovered in great fear. |

|

| ⇑ § IV |

| Quomodo Vespasianum urbs Roma suscipiebat. Et quo pacto Germani post defectionem a Romanis iterum subjugati erant, et Sarmatæ, post incursionem in Mœsiam, sedes suas repetere compulsi erant. | How Vespasian Was Received at Rome ; As Also How the Germans Revolted from the Romans but Were Subdued. That the Sarmatians Overran Mœsia, But Were Compelled to Retire to their Own Country Again. |

| 1 |

— Caput G-22 —

Quomodo Vespasianus rediens a Romanis exceptus est. |

| TITUS autem Cæsar, a patre sibi allato nuntio quod universis quidem Italiæ civitatibus desiderabilis pervenisset, maxime vero, quod urbs eum Roma summa cum alacritate et claritudine suscepisset, in maximam lætitiam voluptatemque translatus est, curis de eo ita ut sibi erat suavissimum liberatus. |

Now Cæsar Titus, with the news having been brought to him from his father that he had indeed arrived as longed-for by all the cities of Italy, but especially that the city of Rome had accepted him with the greatest eagerness and splendor, was transported into the greatest of happiness and pleasure, freed from concern about him so much that it was his greatest delight. |

| Vespasianum enim etiam longe absentem, omnes homines Italiæ voluntatibus, ut præsentem colebant : exspectationem suam, quod nimis eum venire cupiebant, pro ejus adventu ducentes, et omni habentes necessitate liberam erga illum benevolentiam. |

In their yearning all the people of Italy paid homage to Vespasian even while far off, as though he were present — considering their anticipation the same as his arrival, and showing good will toward him free of all compulsion, because they greatly desired him to come. |

| Nam et senatus memor calamitatum, quæ mutatione principum contigissent, optabat imperatorem suscipere senectutis honore bellicorumque gestorum maturitate decoratum, cujus præsentiam sciebat soli saluti subjectorum commodaturam : et populus malis intestinis sollicitus, magis eum venire cupiebat : tunc se calamitatibus quidem pro certo absolvendum esse confidens, antiquam vero libertatem cum opulentia recepturum. |

For the Senate too, mindful of the calamities which had happened due to the change of emperors, chose to accept a general decorated with the distinction of age and the maturity of military accomplishments, one whose presence it knew would conduce only to the safety of the subjects; and the people, worried about civil upheavals, even more wanted him to come, now confident indeed they would definitely be freed from disasters and would regain their old liberty with prosperity. |

| Præcipue milites ad eum respiciebant. Hi enim maxime bellorum per illum patratorum noverant magnitudinem. Imperitiam vero aliorum ducum experti atque ignaviam, magna quidem se optabant turpitudine liberari. Eum vero qui se et servare et honestare solus posset, recipere precabantur. |

The soldiers above all were looking toward him. For they most of all knew the greatness of the wars waged by him. Having experienced the inexperience and cowardice of the other leaders, they sought to be freed of their great disgrace. They prayed to get one who alone could preserve them and give them dignity. |

| Quum vero hac benevolentia diligeretur ab omnibus, honore quidem præcipuis viris ulterius exspectare intolerabile videbatur, sed eum longissime ab urbe Roma convenire ante properabant. Nec tamen quisquam moras ejus conveniendi ferebat, sed ita simul omnes effundebantur, et universis facilius et promptius ire quam manere videbatur, ut etiam civitas ipsa tunc primum inter se jucundam sentiret hominum caritatem. |

Moreover, since he was loved with this goodwill by everyone, it seemed indeed unbearable to the leading men to wait any longer; instead, they hastened to meet him far from the City of Rome. And even so, no one would tolerate the delay in meeting him, but they poured out all together; and to them all it seemed easier and more effortless to go than to remain, so that then for the first time the City itself enjoyed a pleasant dearness of people within itself. |

| Erant autem pauciores abeuntibus remanentes. Ubi vero eum appropinquare indicaretur, quamque mansuete singulos suscepisset, qui præcesserant, nuntiatum est, omnis jam reliqua multitudo per vias cum conjugibus et liberis præstolabantur : et quo transiens advenisset, videndi ejus voluntatem, vultusque lenitatem omnium generum vocibus prosequebantur, benemeritum et salutis datorem, solumque dignum Romanorum principem appellantes. |

Those remaining, rather, were fewer than those leaving. But when it was reported that he was approaching, and it was announced how graciously he had greeted individuals who had gone ahead, the entire remaining multitude waited in anticipation with their wives and children; and where he arrived in passing by, they accompanied their pleasure at seeing him and the gentleness of his countenance with all sorts of cries, calling him benefactor, and giver of safety, and the only ruler worthy of the Romans. |

| Tota vero civitas veluti templum erat, sertis atque odoribus plena. Quum vero vix per circumstantem multitudinem in palatium venire potuisset, ipse quidem penatibus diis adventus sui gratulatoria sacra celebravit. |

Indeed the entire City was like a temple, filled with wreaths and fragrances. But after he had barely gotten through the surrounding multitude to the Palace, he celebrated the rites of thanksgiving for his arrival to his household gods. |

| Vertunt autem se ad epulas turbæ, perque tribus et cognationes et vicinias convivia exercentes, Deo libabant, et ab eo precabantur ipsum Vespasianum quamplurimum temporis in Romano imperio perseverare, et filium ejus, et qui ex his nascerentur servari inexpugnabilem principatum. Urbs quidem Romana Vespasiano ita suscepto, statim maxima felicitate crescebat. |

The masses then turned to banquets and, enjoying parties by tribes and family groups and neighborhoods, sacrificed to God, and prayed of Him that Vespasian himself and his son would continue as long a time as possible on the Roman throne, and that an invincible reign would be preserved to those who were born of them. Indeed, immediately after Vespasian had been received in this way, the City of Rome grew with tremendous prosperity. |

| 2 |

— Caput G-23 —

Domitiani gesta contra Germanos et Gallos. |

| Ante hæc vero tempora, quibus Vespasianus quidem apud Alexandriam erat, Titus vero Hierosolymam obsidebat ; magna pars Germanorum ad defectionem mota est : quibus etiam Gallorum proximi conspirantes, magnam spem contulerant, quod etiam Romanorum dominio liberarentur. |

But before the time when Vespasian was at Alexandria while Titus was besieging Jerusalem, a large part of the Germans was stirred up to rebellion; the neighboring Gauls, conspiring with them, developed the great hope that they might be freed from the domination of the Romans. |

| Germanos autem deficere velle, bellumque inferre, sustulit primo natura bonis consiliis vacua, parva spe appetens periculorum, deinde odium principum, quoniam solis sciunt gentem suam vi coactam servire Romanis : nec non equidem maximam tempus eis fiduciam dedit. |

On the other hand, the Germans were prompted to want to defect and start a war, firstly by a nature devoid of good forethought, seeking danger with little hope, then their hatred of their overlords, because they knew their people was forced to be slaves by the Romans alone; plus, the times indeed instilled the greatest of confidence in them. |

| Nam quum viderent Romanum imperium crebris imperatorum mutationibus intestina seditione turbari, omnemque his subditam orbis terræ partem pendēre ac nutare cognoscerent, hoc sibi optimum tempus ex illorum rebus adversis atque discordiis oblatum esse putaverunt. |

For when they saw the Roman empire being destabilized with internal rebellion through the frequent change of emperors, and they realized that every part of the world subject to them was hanging in suspense and tottering, they concluded that, out of the Romans’ misfortunes and discords, a prime opportunity had been offered to them. |

| Id autem consilium dabant, et hac eos spe decipiebant, Classicus quidam et Civilis, ex eorum potentissimis : qui olim quidem res novas cupiebant : occasione autem inducti, suam sententiam prodidere. |

A certain Classicus and Civilis of their strongest men advanced the plan and deceived them with this hope; certainly these men had been looking for a rebellion for a long time, but motivated by the occasion, they put their ideas forward. |

| Jamque alacriter affectæ multitudinis periculum facturi erant : verum maxima parte Germanorum defectionem pollicita, et ceteris fortasse non dissentientibus, veluti quadam divina providentia, Vespasianus ad Petilium Cerealem, qui pridem Germaniam rexerat, litteras mittit, quibus eum consulem declaravit, jussitque ad Britannias administrandas proficisci. |

And they were going to make a test of the already eagerly disposed multitude; indeed, with a large part of the Germans having already promised their defection and with the rest perhaps not disagreeing, as though through a kind of divine providence, Vespasian sent a letter to Petilius Cerealis, who had earlier governed Germany, through which he appointed him consul and ordered him to proceed to administer the Britains. |

| Igitur ille quo jussus erat abiens, audita rebellione Germanorum, eos jam congregatos aggressus magna clade affecit, depositaque amentia ad sobrietatem coëgit. Sed etiam si ille ad ea loca non pervenisset, tamen haud multo post erant supplicia luituri. |

So he, going off to where he had been ordered, on hearing of the revolt of the Germans, by attacking them when they had already gathered together, inflicted a great defeat on them and forced them, after they set their madness aside, back to sobriety. But even if he had not arrived at that place, they would nevertheless have paid the penalty not much later. |

| Nam ut primum defectionis eorum nuntius allatus est Romam, Domitianus Cæsar hoc audito, non sicut alter in illa ætate fecisset (nam admodum adulescens erat) tantam rei magnitudinem suscipere non detrectavit : sed a patre habens ingenitam fortitudinem et supra ætatem exercitatus, ilico tendebat in Barbaros. |

For as soon as the news of their defection was brought to Rome, Cæsar Domitian, hearing it — not as another would have done at that age (for he was still a young man) —, did not draw back from so immense a task but, having an innate fortitude from his father and being experienced beyond his years, immediately proceeded to the Barbarians. |

| Illi autem expeditionis fame perculsi, ei se permiserunt, lucrum hoc ex ea re maximum nacti, ut sine clade pristino jugo subjicerentur. Omnibus ergo circa Galliam, ut oportuit ordinatis, ne facile rursus unquam turbarentur, Domitianus clarus atque insignis, ætatem superantibus factis, et patrium decus afferentibus, Romam regreditur. |

The latter, however, terrified at the news of his campaign, surrendered to him, taking it as their best gain therefrom to submit to their original yoke without disaster. Having therefore ordered everying around Gaul as it should be so that nothing would ever again be easily disturbed, the illustrious and remarkable Domitian, having accomplished things beyond his age — things contributing to his paternal distinctions —, returned to Rome. |

| 3 |

| Cum supradicta vero Germanorum defectione, eisdem diebus etiam Scytharum convenit audacia. Nam qui appellantur Sarmatæ, maxima multitudine clam transgressi flumen Istrum, violenti atque sævissimi, propter inopinatum impetum multos Romanorum quos in præsidiis offendere, interficiunt : et consularem legatum Fontejum Agrippam, qui fortiter his obvius pugnaverat, occidunt : proximasque regiones totas ferendo atque agendo, omniaque incendendo pervagabantur. |

In those same days, the audacity of the Scythians coincided with the above-mentioned defection of the Germans. For the violent and extremely savage men who are called Sarmatians, having crossed the Danube river in huge numbers, due to their unexpected attack, slaughtered many of the Romans whom they encountered in the guard posts; they also killed the consular legate, Fontejus Agrippa, who had bravely fought against them; and they ranged throughout the whole neighboring region, raiding and plundering and torching everything. |

| Vespasianus autem hoc facto, et vastitate Mœsiæ cognita, Rubrium Gallum mittit pœnas de eis sumpturum. A quo multi quidem in prœliis trucidati sunt. Qui vero salvi esse potuere, cum timore domum refugere. |

However, learning of this event and of the devastation of Mœsia, Vespasian sent Rubrius Gallus to take vengeance on them. Many indeed were slain in battle by him, while those who could save themselves fled home in fear. |

| Hoc autem bello magister militum finito, etiam futuri temporis cautioni consuluit. Pluribus enim et majoribus præsidiis loca circundedit, ut omnino Barbaris esset impossibilis transitus. In Mœsia quidem ea celeritate debellatum est. |

Having finished this war however, the field commander also saw to precautions for the future. For he surrounded the region with many and larger garrisons so that crossings would be utterly impossible for the barbarians. Thus it was that with that speed the war in Mœsia was completed. |

|

| ⇑ § V |

De fluvio Sabbatico, quem in

itinere per Syriam conspicit Titus.

Et quomodo Antiocheni, Tito

supplicantes contra Judæos,

repulsam passi sunt. Deque

triumpho Titi et Vespasiani. | Concerning the Sabbatic River Which Titus Saw as He Was Journeying through Syria ; And how the People of Antioch Came with a Petition to Titus against the Jews but Were Rejected by Him ; as Also Concerning Titus’s and Vespasian’s Triumph. |

| 1 |

— Caput G-24 —

De amne Sabbatico et triumpho Vespasiani ac Titi celeberrimo. |

| PRINCEPS vero Titus aliquandiu quidem Beryti commorabatur, ita ut diximus ; inde autem reversus, et per omnes quas obiret Syriæ civitates magnificentissima celebrans spectacula, Judæorum captivis ad ostentationem cladis eorum abutebatur. Conspicit autem in itinere fluvium cognitione dignissimum. Is fluit medius inter Arcas et Raphanæas Agrippæ regni civitates. |

Now Prince Titus was indeed staying for a while at Beirut, as we have said. But returning from there and celebrating extremely magnificent shows in all the cities of Syria which he passed through, he employed captives of the Jews as a display of their destruction. But on the way he saw a river quite worthy of mention. It flows between the cities of Arca and Agrippa’s Raphanæa. |

| Habet autem quoddam peculiare miraculum. Nam quum sit quando fluit plurimus, neque meatu segnis, tamen interpositis sex diebus a fontibus deficiens, siccum exhibet locum videre. Deinde quasi nulla mutatione facta, septimo die similis exoritur : atque hunc ordinem semper eum observare pro certo compertum est. Unde etiam Sabbaticus appellatus est, a sacro Judæorum septimo die sic denominatus. |

But it has a unique marvel. For although when it flows it is quite abundant and not slow in running, nonetheless, drying up from its sources for six intervening days, it displays a dry bed for the seeing. Then as though making no change, on the seventh day it rises up like it was; and it has been ascertained for certain that it always observes this pattern. Hence it is also called the “Sabbatic,” being thus named after the holy seventh day of the Jews. |

| 2 |

| Civitatis autem Antiochensium populus, postquam Titum adventare cognovit, manere quidem intra mœnia præ gaudio non sustinebat. Omnes autem obviam ei pergere properabant, et usque ad tricesimum vel eo amplius stadium progressi, non modo viri, sed etiam feminæ cum pueris exspectabant. |

Now after the people of the city of Antioch learned that Titus was coming, out of joy they could really not bear to stay within their walls. Instead, they all rushed to go meet him and, having gone as far as the thirtieth or more stade, not just men but even women with their children awaited him. |

| Et quum appropinquantem vidissent ; ex utroque viæ latere stantes dextras cum salutatione tendebant : multisque favoribus exsultantes, cum ipso revertebantur. Crebro autem inter omnes alias laudes precabantur, ut Judæos expelleret civitate. Titus quidem nihil precibus istis indulsit, sed otiose quæ dicebantur audiebat. |

And when they saw him approaching, standing on both sides of the road, they stretched out their right arms in greeting and, rejoicing with many felicitations to him, returned with him. But among all of their other praises, they pled insistently for him to expel the Jews from their city. Despite that, Titus did not give in to these pleas in the least, but did listen in a leisurely way to the things that were being said. |

| Incerti autem quid sentiret, quidve facturus esset, Judæi magno et atroci metu tenebantur. Nec enim commoratus est Antiochiæ Titus, sed continuo ad Zeugma Euphratem versus iter contendit. Quo missi etiam ab rege Parthorum Vologeso venere, auream ei ferentes coronam, quod Judæos vicisset. Eaque suscepta etiam convivium exhibuit regiis, atque ita Antiochiam remeavit. |

Uncertain now about what he was thinking and was about to do, the Jews were struck with great and terrible fear. Yet Titus did not stay at Antioch, but immediately continued on the road toward the Euphrates, to Zeugma. Emissaries from Vologeses, king of the Parthians, had come there bearing a golden crown for his having conquered the Jews. After he had accepted it he also gave a banquet to the royal messengers and therewith returned to Antioch. |

| Senatu vero et populo Antiochensi multum petentibus, ut in theatrum veniret, ubi omnis eum multitudo præstolabatur, humanissime paruit. Rursus autem fortiter eisdem instantibus, et crebro postulantibus expelli civitate Judæos, ingeniose respondit, patriam eorum dicens quo expellendi fuerant interiisse, nullumque jam esse locum, qui eos reciperet. |

At the insistent request of the Antiochene senate and people to come to the theater where the entire multitude awaited him, he politely complied. But while the same ones again strongly pressed him and repeatedly demanded that the Jews be expelled from the city, he replied appositely, saying that their fatherland — where they would have been expelled to — had been destroyed, and that there was now no place that would accept them. |

| Unde ad aliam petitionem sese convertunt Antiochenses, quod priorem impetrare non potuerunt. Æneas enim tabulas eum precabantur eximere, quibus incisa essent privilegia Judæorum. Sed ne id quidem Titus annuit. Verum in eodem statu relictis omnibus, quæ habebant apud Antiochiam Judæi, ad Ægyptum inde discessit. |

Hence the Antiochenes turned to another request, since they could not obtain their first one. They pled for him to remove the bronze tables on which the privileges of the Jews were inscribed. But Titus did not assent even to this. Instead, leaving in the same state everything which the Jews had at Antioch, he left from there for Egypt. |

| Iter autem agendo quum ad Hierosolymam venisset, tristemque solitudinem quam videbat, antiquæ civitatis claritudini compararet, disjectorum operum magnitudinem et veterem pulchritudinem recordatus, miserabatur excidium civitatis, non sicut alius fecisset exsultans, quod talem ac tantam funditus excidisset, verum multa imprecans seditionis auctoribus, et qui hanc pœnam ei inferre coëgere : ita certus erat, quod nunquam virtutem suam voluisset punitorum calamitate clarescere. |

When, making his way, he had come to Jerusalem and compared the depressing desolation which he saw to the former splendor of the City, remembering the magnitude of the shattered works and their old beauty, he felt sorry for the destruction of the City, not, as someone else would have done, rejoicing over the fact that he had utterly annihilated such and so great a place, but oftentimes cursing the authors of the insurgency and those who had forced him to inflict that punishment on it; thus it was clear that he would never have wanted his valor to shine through the destruction of those punished. |

| Ex magnis enim divitiis non minima pars in ruinis adhuc inveniebatur. Quædam enim eruebant Romani, plura vero captivis indicantibus auferebant, aurum atque argentum, aliaque instrumenta pretiosissima, quæ domini propter incertam belli fortunam terræ condidere. |

For out of the great riches, no small part was still being found in the ruins. The Romans dug out some, while they carried away more after the captives pointed it out: gold and silver and other extremely costly objects which their lords had buried on account of the uncertain fortunes of war. |

| 3 |

| Titus autem, propositum iter ad Ægyptum tendens, emensa velociter solitudine, pervenit Alexandriam : decretoque ad Italiam navigare, quum se duæ legiones comitarentur, utramque unde venerant remisit : Quintam quidem in Mœsiam, Quintam vero Decimam in Pannoniam. |

However Titus, proceeding on his intended way, after speedily crossing the desert, arrived at Alexandria; and, having decided to sail to Italy, since two legions had been accompanying him, he sent them both back to where they had come from: the Fifth to Mœsia and the Fifteenth to Pannonia. |

| Captivorum autem duces Simonem et Joannem, et alios numero septingentos viros electos, tam magnitudine corporum quam pulchritudine præstantes, ilico ad Italiam portari præcepit, cupiens eos in triumpho traducere. Peracta vero navigatione pro voto, similiter quidem Roma in eo suscipiendo erat affecta, et occursus exhibuit eos quos patri. Claritudinem vero Tito pater attulit, qui venit obviam, eumque suscepit. Multitudini autem civium divinam quandam lætitiam suggerebat, quod videbat in unum tres convenisse. |

On the spot he ordered the leaders of the captives, Simon and John, and other chosen men, seven hundred in number, outstanding in bodily size as well as handsomeness, to be transported to Italy, desiring to lead them in his triumphal procession. After he had then made the voyage as desired, Rome in greeting him was in a mood, and showed a reception, similar to what it had displayed to his father. But his father, who came to meet and greet him, added to Tito’s renown. For it brought a kind of numinous joy to the mass of citizens to see the three come together as one. |

| Non multis autem diebus post, unum communem triumphum ob res gestas agere statuere, quamvis utrique senatus proprium decrevisset. Prædicto autem die, quo futura erat pompa victoriæ, nemo ex tam infinita civitatis multitudine domi remansit. Omnes autem quum exissent, loca ubi tantum stare possent occupaverant, quantus spectandis imperatoribus modus sufficeret, concesso necessario transitu. |

Not many days later, they decided to celebrate a single common triumph for the deeds, even though the Senate had decreed one to each of the two. On the pre-announced day, when the coming victory procession was to take place, no one out of such an innumerable multitude of the citizenry remained home. Indeed, when they all came out, they took up positions wherever they could even only stand; for the generals who were to be viewed there was only as much space as was necessarily allowed for the passage. |

| 4 |

| Cuncta vero turba militari ante lucem per turmas atque ordines progressa cum rectoribus suis, et circa ostia constituta non palatii superioris, sed prope Isidis templum (ibi enim principes nocte illa quiescebant), prima jam aurora incipiente procedunt Vespasianus et Titus lauro quidem coronati, amicti vero patria veste purpurea : et ad Octavianas ambulationes transeunt. |

But with the entire military body having marched out by units and ranks with their leaders, and having been stationed around the doors, not of the upper palace, but near the temple of Isis (for the princes had rested there for that night), now at the first rays of dawn Vespasian and Titus came out, crowned, of course, with laurel, but dressed in their crimson national garments, and crossed over to the Walkways of Octavia. |

| Ibi enim senatus, et ducum prŏcĕres, et honorati equites, eorum præstolabantur adventum. Tribunal autem ante porticus factum erat, sellæque eburneæ in eo præparatæ. Quo quum ascendissent, consederunt. Statimque eos militaris favor excepit, multis virtutem testimoniis prædicans. Illi autem inermes erant, in veste serica laureis coronati. |

For there the Senate and the foremost of the magistrates and the honored knights were awaiting their arrival. Moreover a platform had been erected before the Colonnades, and ivory seats set up on it. After climbing up on it, they sat down. And immediately military acclamation greeted them, greatly commending their valor with many attestations. Those men, as well, were unarmed, in silk garments, crowned with laurel. |

| Perceptis autem laudibus eorum Vespasianus, quum dicere adhuc vellent, silentii signum dedit. Magnaque omnium quiete facta surrexit, et amictu magnam partem capitis adopertus, sollemnia vota celebravit : idemque Titus fecit. Perfectis autem votis, Vespasianus in commune omnes breviter allocutus, milites quidem ad prandium, quod his ex more ab imperatore parari solet, dimittit. |

Then, receiving their praise, Vespasian, although they still wanted to speak, gave a sign for silence. And after a great quiet of everyone came about, he rose and, covering a large part of his head with his garment, pronounced the traditional vows; and Titus did the same. With the vows finished, Vespasian spoke briefly to them all in common, then sent the soldiers off to the breakfast which is by custom normally prepared for them by the general. |

| Ipse vero ad portam recedit, quæ ab eo quod per illam semper triumphorum pompa ducitur, nomen accepit. Ibi et cibum prius capiebant, et triumphalibus vestibus amicti, diis ad portam collocatis cæsa hostia, inter spectacula transeuntes triumphum ducebant, ut multitudini facilior præberetur aspectus. |

But he himself went back to the gate which takes its name from the fact that a triumphal parade is always led through it. There they first took their meal and, clothed in the triumphal garments, having sacrificed a victim to the gods located at the gate, led the procession while passing through the shows so that a better view would be granted to the multitudes. |

| 5 |

| Pro merito autem narrari multitudo eorum spectaculorum et magnificentia non potest, in omnibus quæ quisque cogitaverit, vel artium factis, vel divitiarum opibus, vel naturæ novitate. Nam pæne quæcunque hominibus, qui usquam sunt, fortunatis paulatim quæsita sint — aliis alia mirabilia atque magnifica —, hæc universa illa die Romani imperii magnitudinem probavere. |

What cannot be described is the number of their shows and their magnificence in every way that anyone could imagine — whether made by skill, or through the power of riches, or by the creativeness of nature. For almost whatever things had been slowly acquired by fortunate men who ever were — different things marvelous and magnificent among the different individuals —, on that day all these things demonstrated the immensity of the Roman empire. |

| Etenim argenti aurique nec non eboris in omni specie operum multitudinem, non ut in pompa ferri cerneres, sed ut ita dixerim omnia fluere. Et alias quidem vestes ex rarissimis generibus purpuræ portari, alias diligentissima pictura variatas arte Babylonia : gemmæ autem clarissimæ tam multæ, aliæ coronis aureis, aliæ aliis operibus inclusæ traductæ sunt, ut appārēret frustra nos earum usquam rarum esse aliquid suspicari. |

For indeed, you could see a vast amount of silver and gold as well as ivory in every sort of elaboration, not being carried along as in a parade but, as I might say, all of it flowing, and some garments of the rarest types of crimson being carried, others variegated with the most careful paintings after the Babylonian manner; whereas so many brilliant gems, some set into gold crowns, others into other works, were transported that it seemed mistaken for us to suspect them of ever being something rare. |

| Ferebantur etiam simulacra, quæ illi deos habent, et magnitudine mirabili, et arte non defunctorie facta. Horumque nihil non ex pretiosa materia. Quin et animalium diversa genera producebantur, propriis ornamentis induta. Erat autem etiam quæ singula portaret magna hominum multitudo, purpureis vestibus atque inauratis ornata. |

Borne along too were images which the Romans consider gods, both marvelous in size and made with a skill not careless. Of them, nothing was not of precious material. On top of that, different types of animals were drawn along, dressed in their own finery. Moreover there was a large number of men, ornamented with scarlet and gold-interwoven garments, that carried the individual items. |

| Ipsi etiam qui ad pompam fuerant ab alia turba discreti, præcipua et mirabili ornamentorum magnificentia culti erant. Insuper his, ne captivorum quidem vulgus inornatum videres, sed varietas et pulchritudo quidem vestium natam ex fatigatione corporum deformitatem, oculis subtrahebat. Maxime autem stupori erat, pegmatum quæ portabantur, fabricatio, pro cujus magnitudine timendum viribus portantium occurrentes putabant. |

Even the very ones who had been separated from the rest of the crowd for the parade were dressed with a spectacular and wonderful magnificence of ornamentation. On top of that, you did not see even the mob of captives unadorned, but the variety and indeed the beauty of their garments hid the overfatigue-caused ugliness of their bodies from the eyes. But most amazing of all was the construction of the floats that were carried along, on account of whose size those encountering them thought there should be worry about the strength of the carriers. |

| Multa enim in tertium nidum quartumque surgebant : et magnificentia fabricæ cum admiratione delectabat : multis aurata veste circundatis, quum aurum præterea factum atque ebur omnibus esset affixum. Multis autem imitationibus bellum aliter in alia divisum, certam sui faciem demonstrabat. |

For many rose up into a third and fourth tier, and the magnificence of construction provided delight with admiration, with many wrapped in gilded drapery, while wrought gold and ivory was besides attached to everything. With many depictions the war, variously sectioned into various elements, showed a realistic portrait of itself. |

| Erat enim cernere vastari quidem fortunatissimam terram, totas vero interfici acies hostium : et alios fugere, alios captivos duci : murosque excellentes magnitudine machinis dirui, et castellorum exscindi munimina, et populosarum civitatum mœnia disturbari, exercitumque intra muros infundi : cædisque omnia loca plena, et eorum qui manu resistere non poterant preces : ignemque templis immissum, ædiumque super dominos post multam vastationem eversiones : atque amnis tristitiam, defluentis non in arva culta, neque ad hominum vel pecorum potum, sed per terram ex omni parte flagrantem. |

There was a view of an extremely prosperous land being laid waste, of entire divisions of the enemy being annihilated, and some fleeing, others being led captive, and of walls of towering size being demolished by machines, and the fortifications of strongholds being obliterated, and the walls of populous cities being destroyed, and an army being poured into the walls; and of all areas filled with slaughter, and of the pleadings of those who could not resist with their hands, and of fire being thrown into the temples, and the collapses of buildings atop their owners after great devastation, and the sadness of a stream flowing, not into cultivated fields or for drink for men or cattle, but through a land burning on all sides. |

| Hæc enim Judæi bello passi sunt : ars autem et confectorum operum magnitudo, nescientibus adhuc facta tanquam præsentibus ostendebant. Erat autem per singula pegmata captæ civitatis dux, ita ut captus fuerat ordinatus. Multæ etiam naves sequebantur. |

For the Jews had suffered these things. But the art and size of the finished works displayed the events to those still unaware as though they had been present at them. Moreover on each of the individual floats was a leader of a captured city, arranged just as he had been captured. Many ships followed as well. |

The Triumphal Procession of Titus

(Digitally Restored and Colored by the Arch of Titus Project) |

| Spolia vero alia quidem passim ferebantur. Eminebant autem ea quæ apud Hierosolymam in templo reperta sunt, mensa aurea ponderis talenti magni, et candelabrum similiter quidem auro factum, sed opere commutato ab usus nostri consuetudine. Nam media quidem columna basi hærebat, tenues autem ab ea cannulæ producebantur, formatæ ad similitudinem fuscinæ, ad summum quæque in lychni speciem fabricatæ. |

Indeed, other booty was being borne everywhere. But the things which were found in the Temple in Jerusalem stood out: a gold table of the weight of a mega-talent, and a candelabrum similarly made of gold, but with a structure altered from the conventions of our usage. For, while the middle column was affixed to the base, thin pipes came out of it, formed in the likeness of a pitchfork, each fashioned at the top in the form of a lamp. |

| Erant autem numero septem, septimi diei, qui apud Judeos est, indicantes honorem. Post hæc autem portabatur lex Judæorum, novissima spoliorum. Deinde transibant plurimi victoriæ simulacra portantes, omnia ex auro et ex ebore facta. Post hæc Vespasianus prior ibat, et Titus deinde sequebatur. Domitianus autem adequitabat, ipse quoque ornatus pulchritudine, dignumque spectari exhibens equum. |

Moreover, in number they were seven, symbolizing honor of what among Jews is the seventh day. Then after that was borne the Law of the Jews, the last of the spoils. Next, many men went past carrying effigies of Victory, all made of gold and ivory. After them, Vespasian came first, and then Titus followed. On the other hand, riding along on horseback was Domitian, himself also resplendently adorned and displaying a horse deserving to be seen. |

| 6 |

| Pompæ autem finis fuit Capitolini Jovis templum, quo postquam ventum est, constitere. Erat autem vetus mos patrius, operiri donec ducis hostium mortem quispiam nuntiaret. Is erat Simon Gioræ, tunc inter captivos in pompa traductus : laqueo vero circundatus per forum trahebatur, quo eum simul cæderent qui ducebant. |

Now the end of the parade was the temple of Capitoline Jupiter where, after it arrived there, they stopped. It was, however, an old national custom to wait until someone announced the death of the enemy leader. That was Simon, son of Gioras, at that time drawn along in the parade among the captives; he was dragged with a noose around him through the forum where those who were pulling him might simultaneously kill him. |

| Lex autem Romanis est, ibi necare criminum reos morte damnatos. Postquam igitur eum finem vitæ habere nuntiatum est, omniumque favor secutus est, tunc hostias incohavere. Hisque secundo per vota sollemnia omine peractis, in palatium recessere. |

It is, moreover, a law among the Romans to execute at that place those condemned to death as guilty of crimes. So after it was announced that he had had the end of his life, and everyone’s applause followed it, they then began with the sacrifices. And having finished these under favorable auspices through the established prayers, they returned to the palace. |

| Et alios quidem epulis ipsi excepere, aliis autem omnibus domi conviviorum instructi erant apparatus. Hunc enim diem urbs Romana celebrabat, victoriæ quidem in hostes gratulatorium, finem vero malorum civilium, et spei bonæ pro felicitate principium. |

And they themselves invited some in to their banquets, while for all others preparations were made for feasts at home. For the Roman city celebrated that day as one, certainly, of thanksgiving for victory over the enemy, but as the end of civil disorders and the beginning of good hope for prosperity. |

| 7 |

| Post triumphos vero, et Romani imperii firmissimum statum, Vespasianus Paci templum ædificari decrevit. Itaque mira celeritate, et qua hominum cogitationem superaret, effectum est. Magna enim divitiarum largitate usus, insuper perfectis id picturæ ac figmentorum operibus exornavit. |

But after the triumphal parades and the extremely firm stabilization of the Roman empire, Vespasian decreed that a temple be built to Peace. And so it was constructed — with amazing speed, and such as would surpass human expectations. For in addition, employing a great lavishness of riches, he adorned it with prefabricated works of painting and statuary. |

| Omnia namque in illud fanum collecta ac deposita sunt, quorum visendorum studio per totum orbem, qui ante nos fuerunt, vagabantur, quomodo aliud apud alios situm esset, videre cupientes. Hic autem reposuit etiam quæ Judæorum fuerant instrumenta, his se magnifice ferens. Legem vero eorum, et penetralium vela purpurea in palatio condita servari præcepit. |

Indeed, in that sanctuary were collected and placed all the things, out of the desire of seeing which those who lived before us crisscrossed the entire world, desiring to see how a thing might be found among others. Moreover he also placed here the instruments which had belonged to the Jews, being immensely proud of them. But their Law and the crimson veil of the inner sanctum he ordered kept secreted in the Palace. |

|

| ⇑ § VI |

De Machærunte ;

et quomodo castellum aliaque

loca capit Lucilius Bassus. | Concerning Machærus, and How Lucilius Bassus Took That Citadel and Other Places. |

| 1 |

— Caput G-25 —

Herodium et Machærus a Basso capta. |

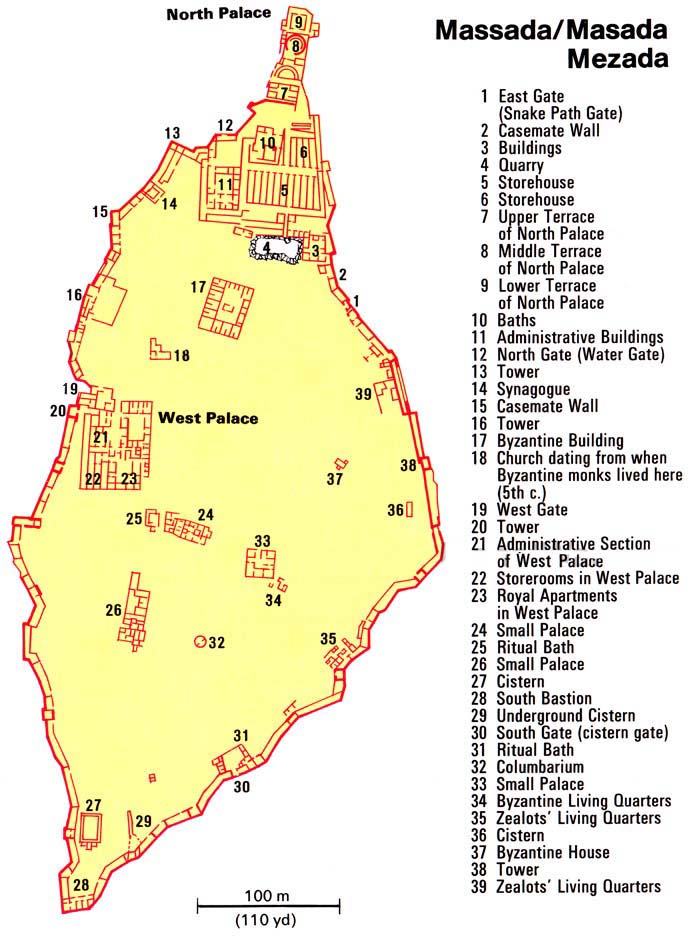

| IN Judæam vero legatus missus Lucilius Bassus, suscepto a Cereali Vetiliano exercitu, castellum quidem Herodion cum præsidio deditione cepit. Post autem omni manu militari collecta (multi autem in partes divisi erant), et Legione Decima bellum inferre Machærunti statuit. Valde enim necessarium videbatur id exscindi castellum, ne multos sui munimine ad defectionem invitaret. |

On the other hand, Lucilius Bassus, sent as legate to Judæa, having taken over the army from Cerealis Vetilianus, captured the fortress Herodium with its garrison by surrender. But after that, having gathered all the army groups together (given that many men had been divided up into sections), with the Tenth Legion he also decided to make war on Machærus. For it seemed quite necessary to eradicate that fortress so that with its fortifications it would not invite a lot of men to defection. |

| Nam et salutis spem habitatoribus certam, et aggredientibus hæsitationem atque formidinem, natura loci præstare maxime poterat. Nam ipsum quidem quod muro cinctum est, saxosus est collis, in proceram altitudinem surgens, et ob hoc etiam capi difficilis videtur : sed ne vel accedi posset eo natura excogitarat, quæ vallibus eum ex omni parte vallaverat, quarum altitudo oculis comprehendi non posset : nec transire erat facile, nec aggestu ulla ratione compleri possibile. |

For the nature of the place was especially able to engender a firm hope of safety in its residents and fear and hesitation in attackers. For indeed, the very thing that was surrounded by a wall is a rocky hill rising to a lofty height and, for that reason, appears difficult to capture; but nature had contrived to make it impossible for it even to be approached at that place; she had walled it on every side with valleys whose depth could not be plumbed with the eyes; neither was it easy to cross them, nor in any way possible to stuff them up with fill. |

Machærus at sunset |

| Nam ea quæ ab Occidente secat vallis LX• stadiis distenditur, unde Asphaltites lacus ei limitem facit. Ex hoc vero tractu ipse Machærus altissimo vertice supereminet. |

For the valley which cuts in from the west extends seven miles {(Latin: 60 stades)} from where the Dead Sea forms its start. In fact, from this region Machærus itself rises up with its extremely high summit. |

| A Septentrione autem et Meridie, valles magnitudine quidem supradicta cingunt, similiter vero sunt inextricabiles ad oppugnationem. Ejus vero vallis quæ ab Oriente est, altitudo non minor centum cubitis invenitur : monte vero ex adverso Machærunti posito terminatur. |

Moreover, valleys of the aforementioned size surround it on the north and south; they are, however, similarly impracticable for an attack. Plus, of the valley that is on the east, the depth is found to be not less than a hundred fifty feet {(100 cubits)}; it in turn is bounded by a mountain located opposite Machærus. |

| 2 |

| Ea loci natura perspecta, rex Alexander primus in eo castellum communivit, quod postea Gabinius bello cum Aristobulo gesto deposuit. Herodi autem regnanti, omnibus locis dignior quum visus est, et constructione tutissima, propter Arabum præcipue vicinitatem. Namque opportune situs est, eorum fines prospectans. |

Having surveyed the nature of the place, King Alexander {(Jannæus, 104-78 B.C.)} was the first to construct on it a fortress, which Gabinius {(Pompey’s legate)} in the war with Aristobulus later destroyed. But while Herod was reigning, it seemed more deserving of the strongest construction — including, than all other places —, especially on account of the proximity of the Arabs. For it is opportunely situated, looking out on their territory. |

| Magno ergo locum muro amplexus ac turribus, civitatem illic fecit incolis, unde in arcem ipsam ferebat ascensus. Quin et circa ipsum verticem rursus murum ædificaverat, turresque in angulis sexagenorum cubitorum erexerat. In medio autem ambitu regiam struxerat, magnitudine simul habitationum et pulchritudine locupletem. |

Hence, having surrounded the place with a large wall and towers, he made a city there for the inhabitants, whence an ascent led up to the citadel itself. Additionally, he had also again built a wall around the summit and on its corners erected towers ninety feet {(60 cubits)} in height. In the center of the roundabout he had constructed a palace, rich in both the size and beauty of its apartments. |

| Multas vero cisternas recipiendis aquis abundeque suppeditandis, locis maxime idoneis fecerat : veluti cum natura certaret, ut quod illa situ loci expugnabile fecerat, ipse manu structis munitionibus superaret. Insuper enim et sagittarum multitudinem machinarumque reposuit : et omnem apparatum excogitavit, qui habitatoribus posset magnæ obsidionis præstare contemptum. |

Further, at quite suitable points he had made cisterns for catching and abundantly supplying rainwater — as though he were competing with nature, so that what she, by the siting of the place, had made conquerable, he himself might overcome through fortifications made by hand. For in addition he stored a large quantity of arrows and artillery, and invented every device which could allow the inhabitants to defy a long siege. |

| 3 |

| Erat autem in ipsa regia ruta mirabilis magnitudinis : a nulla enim ficu vel celsitudine, vel magnitudine vincebatur. Ferebant autem eam ex Herodis temporibus perseverasse : mansissetque ulterius profecto, sed ab Judæis qui locum ceperant excisa est. |

Also, in the palace itself there was a rue plant of amazing size, for it was exceeded by no fig tree height or size. Indeed, they say that it had endured from the times of Herod; and it would certainly have lasted longer, but it was cut down by the Jews who had captured the place. |

| Vallis autem, qua civitas a parte Septentrionali cingitur, quidam locus Baaras appellatur, ubi radix eodem nomine gignitur : quæ flammæ quidem assimilis est colore, circa vesperam vero veluti jubare fulgurans, accedentibus eamque evellere cupientibus facilis non est : sed tam diu refugit nec prius manet, quam si quis urinam muliebrem vel menstruum sanguinem super eam fuderit. |

Moreover the ravine by which the city is compassed on the northern side is a certain place called by the name of “Baäras,” whence a root of the same name is derived, one which, similar in color to a flame, flashing as though with a halo around evening, is not easy for those coming wanting to pull it out; rather, it shrinks back and will not stay until one pours a woman’s urine or menstrual blood on it. |

| Quinetiam tunc si quis eam tetigerit, mors certa est, nisi forte illam ipsam radicem ferat de manu pendentem. Capitur autem alio quoque modo sine periculo, qui talis est : totam enim circumfodiunt, ita ut minimum ex radice terra sit conditum. Deinde ab ea religant canem : illoque sequi eum a quo relegatus est cupiente ; radix quidem facile evellitur : canis vero continuo moritur, tanquam ejus vice a quo herba tollenda erat, traditus. Nullus enim postea accipientibus metus est. |

And even then if one touches it, death is certain, unless perhaps he carries the root itself hanging from his hand. It is, however, also taken without danger in another way, which is as follows: they dig around the whole of it in such a way that a minimum of the root is covered by earth. Then they tie a dog to it, one wanting to follow him by whom he is tied; the root is then easily pulled out, but the dog dies immediately, as though handed over in the place of him by whom the plant was to be taken out. For afterwards there is no fear for those handling it. |

| Tantis autem periculis propter unam vim capi eam operæ pretium est. Nam quae vocantur dæmonia, pessimorum hominum spiritus, vivis immersa, eosque necantia quibus subventum non fuerit, hæc cito, etiam si tantummodo admoveatur ægrotantibus, abigit. Fluunt autem ex eo loco aquarum fontes etiam calidarum, multum inter se sapore diversi. Alii namque amari sunt : aliis nihil dulcedinis deest. |

However it is worthwhile for it to be taken under such dangers on account of one property: for if it is only just touched on the sick, it quickly expels so-called demons, the spirits of extremely evil men infecting the living and killing those who are not given help. But from that area also flow springs of hot water, differing greatly in taste from one another. For while some are bitter, nothing of sweetness is lacking in others. |

| Multi autem frigidæ aquæ ortus, non solum in humilioribus locis fontes alternos habent, sed quod amplius quis miretur, in proximo quædam spelunca cernitur, non quidem alte cava, saxo autem imminente protecta : super hoc veluti duæ mammæ inter se paululum distantes eminent : et altera quidem frigidissimum fontem, altera calidissimum fundit : qui mixti lavacrum suavissimum præbent, multisque morbis ac vitiis salutare, maxime vero nervorum curationi conveniens : habetque idem locus metalla, sulfuris et aluminis. |

However, many sources of cold water have springs sporadically alternating not only in lower places but, what one would find more surprising, a certain cave is found in the vicinity, certainly not deeply hollowed out, but protected by a projecting rock; above this stand out as it were two breasts a little apart from one another; and the one pours out an extremely cold spring, the other an extremely hot one. Mixed together, these provide a most soothing bath, healthful for many sicknesses and deficiencies, but especially suitable for curing the muscles; and the same place has mines of sulfur and alum. |

| 4 |

| Bassus autem contemplatus undique regionem, valle Orientali repleta accessum parare statuit : opusque incohavit, properans aggerem quam plurimum extollere, facilemque per eum oppugnationem facere. |

Now Bassus, having reviewed the region from all sides, decided to construct his approach by filling the eastern ravine, and started on the work, hurrying to raise the bulwark as much as possible and thereby to make the siege easier. |

| Qui vero intus fuerant deprehensi, ab externis segregati Judæi, illos quidem coëgere, inane vulgus esse existimantes, inferiorem observare civitatem, ac pericula priores excipere : superius vero castellum ipsi occupatum tenebant, et propter munitionis firmitatem, et ut saluti suæ consulerent. |

But those Jews who had been caught inside, having been separated from the aliens, forced them — considering them worthless rabble — to keep to the lower city and be the first to meet the dangers; they themselves held the upper fortress in their possession both on account of the solidity of its fortification and to look after their own safety. |

| Impetraturos enim se veniam opinabantur, si locum tradidissent Romanis. Prius autem volebunt spem declinandæ obsidionis experiendo convincere : ideoque alacri animo in dies singulos excursus habebant, et cum his quos sors obtulisset consertis manibus, multi moriebantur, multosque Romanos interficiebant. |

For they thought they would obtain pardon if they were to surrender the place to the Romans. But first they wanted by experimentation to try out their hope of deflecting the siege; and so every day with vigorous spirits they made sallies, and with those whom chance presented them with in hand-to-hand combat, many died, and they slew many Romans. |

| Semper autem utrisque ex tempore plus victoriæ captabatur : Judæis quidem, si incautiores aggrederentur : in aggere autem positis, si improvisum excursum eorum bene sæpti armis exciperent. Sed non is erat finis obsidionis futurus. Res autem quædam fortuito gesta, inopinatam castelli tradendi necessitatem Judæis imposuit. |

But on both sides more victory was always obtained from the moment: for the Jews, if they attacked men off their guard; on the other hand, for those stationed on the bulwark, if well surrounded with arms they took on the sudden onslaught. But that was not to be the end of the siege. Rather, a certain exploit occurring by chance imposed on the Jews the unexpected necessity of surrendering the fortress. |

| Erat inter obsessos juvenis et audacia ferox, et manu strenuus, Eleazarus nomine. Is autem fuerat excursibus nobilis, multos egredi aggestumque prohibere obsecrans, et in prœliis semper graviter Romanos afficiens : audaciaque sua socios prosequens, impetum quidem facilem his, periculo autem vacuum discessum efficiebat novissimus recedendo. |

Among the besieged there was a young man fierce in audacity and strong of arm by the name of Eleazar. He was distinguished in the sallies, urging many men to go out and stop the dirt-filling, and in battles always injuring the Romans severely; accompanying his comrades with audacity, he truly made the attack easy for them while making their retreat danger-free by being the last in withdrawing. |

| Itaque discreta quodam die pugna, et utraque parte digressa, ipse tanquam despiciens omnes, existimans neminem tunc hostium prœlium excepturum, extra portam remansit : et in muro stantes alloquebatur tota mente illos attendens. Hanc autem opportunitatem vidit quidam ex castris Romanorum Ægyptius, nomine Rufus : et quod nemo sperasset, impetu facto cum ipsis eum armis repente correptum, quum hoc viso stantes in muro stupor teneret, in castra Romanorum traduxit. |