DE BELLO JUDAICO

LIBER TERTIUS |

THE JEWISH WAR

BOOK THREE |

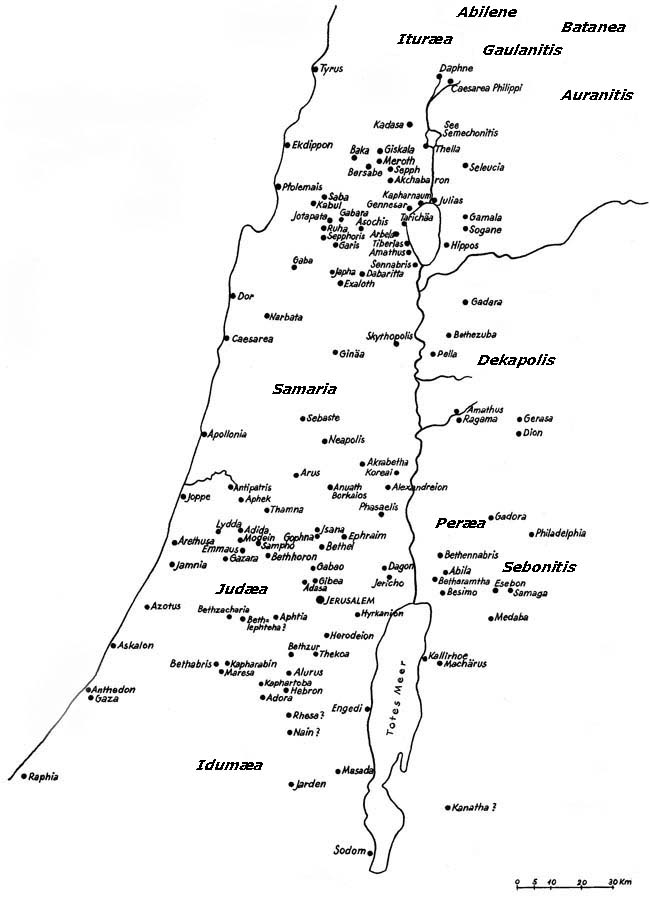

Palæstina

with locations mentioned by Josephus

|

| Book 3 |

| From Vespasian’s coming to Subdue the Jews to the Taking of Gamala |

|

| ⇑ § I |

Vespasianus a Nerone

mittitur in Syriam,

ut Judæos bello aggrediatur. | Vespasian is sent into Syria by Nero in order to make war with the Jews. |

| 1 |

— Caput C-1 —

De successoribus Herodis, et ultione direptæ aureæ aquilæ. |

| Neronem autem, ubi res apud Judæam non prospere gestas accepit, latens quidem, quod necesse fuit, cum timore stupor invadit ; aperte autem superbiam simulans ultro etiam indignabatur ; magisque ducis neglegentia quam virtute hostium quæ contigerant facta esse dicebat, decere se putans propter pondus imperii tristiora contemnere viderique malis omnibus superiorem animum gerere ; verumtamen curis arguebatur mentis ejus perturbatio, quum deliberaret cuinam commotum crederet Orientem, qui una et Judæos rebellantes ulcisceretur proximasque his nationes simili morbo correptas antecaperet. |

When Nero was informed of the reverses in Judæa, he was struck with bewilderment and fear — of course hidden, which was necessary; but outwardly simulating arrogance, on his part he displayed anger: it was because of the commander’s negligence, he said, not the enemy’s prowess, that what had happened had come about. He felt that the burden of empire obliged him to treat bad news with disdain and to appear to maintain a mind superior to all misfortunes. Nevertheless the turmoil of his spirit was betrayed by his worry as he was debated to whom he could entrust the East in its disturbed state, who would both punish the rebelling Jews and prevent the spread of a similar infection to surrounding nations. |

| 2 |

| Invenit igitur solum Vespasianum his necessitatibus parem et qui tanti belli magnitudinem suscipere posset, virum ab adolescentia usque ad senectutem bellis exercitatum, et qui populo Romano jam pridem pacasset Occidentem, Germanorum tumultu concussum, armisque ante illud tempus incognitam Britanniam vindicasset. Unde patri quoque ipsius Claudio præstiterat, ut sine proprio sudore triumpharet. |

He found no one but Vespasian equal to the task and capable of understaking a war on such a tremendous scale. Vespasian had served in wars from his youth to his mature years; years before he had subjugated to the Roman people a West shaken by a rebellion of the Germans; by force of arms he had acquired Britain, till then unknown, so enabling Nero’s father Claudius to celebrate a triumph without a drop of his own sweat. |

| 3 |

| Itaque his omnibus fretus, ætatemque illius cum peritia stabilem cernens, obsidesque fidei liberos, eorumque florem manus esse paternæ prudentiæ, jam tum fortasse de tota Republica Deo aliquid ordinante, mittit eum ad regendos exercitus in Syria constitutos, multis pro tempore blandimentis atque obsequiis animatum, qualia necessitas imperare consuevit. Ille autem protinus ex Achaja, ubi cum Nerone fuerat, Titum quidem filium suum mittit Alexandriam, ut inde Quintam itemque Decimam Legiones moveret. Ipse vero, transmissus ad Hellespontum, terreno itinere in Syriam pervenit, ibique Romanas vires multaque a vicinis regibus auxilia congregavit. |

Considering all these things, he recognized that the man was experienced and of stable age, and that his sons were, moreover, hostages for his good faith and, being in the prime of life, could provide the hands if their father provided the brains. Perhaps also God was already planning something involving the entire empire. For whatever reason, Nero sent this man to assume command of the armies in Syria, paying him in view of the situation every smooth blandishment and compliment that necessity can suggest. From Greece, where he was on Nero’s staff, Vespasian dispatched his son Titus to Alexandria to fetch the Fifth and Tenth Legions {(actually only one legion, the Fifteenth)} from there; he himself crossed the Hellespont and travelled overland to Syria. There he concentrated the Roman forces and large allied contingents provided by neighboring kings. |

|

| ⇑ § II |

Magna Judæorum cædes

circa Ascalonem.

Vespasianus Ptolemaïdem venit. | A great slaughter about Ascalon. Vespasian comes to Ptolemais. |

| 1 |

| AT Judæi, post malam Cestii pugnam insperata felicitate sublati, animorum impetus cohibere non poterant ; sed tanquam Fortuna eos exagitante perciti, bellum ulterius producebant. Denique omni, quanta fuit, manu pugnacissima congregata, Ascalonem petierunt. Ea est civitas antiqua, DCC• et XX• stadiorum spatio ab Hierosolyma distans, et Judæis semper invisa ; quæ res fecit, ut etiam tunc primis eorum incursibus propior videretur. Tres autem viros aggressionis duces habebant, et corporibus et prudentia præstantissimos, Nigrum Peraitam, et Silam Babylonium, et Johannem Essenum. Ascalon vero validissimo quidem muro cincta erat, sed vacua pæne præsidiis. Una enim cohors eam peditum, et una equitum ala tuebatur, cui præfectus erat Antonius. |

After the defeat of Cestius the Jews were so elated by their unexpected success that they could not control their emotions, and as if whipped up by a driving Fate, they expanded the war further. As a result, gathering the largest possible warlike band, they made for Ascalon. This is an old town eighty-three miles from Jerusalem, and always hostile to the Jews, so that even then it seemed closer than their first attacks. The expedition was led by three men of unequalled prowess and intelligenced, Niger from Peræa, Silas the Babylonian, and John the Essene. Ascalon was girded by an extremely strong wall, but was almost completely devoid of defenders; it was garrisoned by one infantry cohort and one cavalry squadron, commanded by Antonius. |

| 2 |

| Illi igitur ira multa velocius itinere peracto ac si ex propinquo venirent, præsto erant. Antonius vero (nec enim eorum fore impetum nesciebat) equites jam ex civitate duxerat, et neque multitudinem veritus vel audaciam, primas hostium coitiones fortiter sustinuit, murumque properantes aggredi refrenavit. Itaque Judæi, qui cum peritioribus imperiti, et pedites cum equitibus, cum stipatis autem inordinati, leviterque armati cum instructis, plusque indignationi quam consilio tribuentes, cum morigeris et nutu rectoris omnia facientibus dimicabant, facile profligantur. Nam ut semel eorum primæ ab equitibus turbatæ sunt acies, fugam petunt ; et murum versus se a tergo urgentibus incidentes, suimetipsi hostes erant, donec omnes incursibus equitum victi, per totum campum dispersi sunt, qui fuit plurimus, totusque habilis equitantibus ; quod quidem Romanos juvit, ut magna cæde Judæos prosternerent. |

Hence, impelled by great anger, they showed up after covering the distance faster than if they had come from nearby. Antonius, however (who had not been unaware of their coming attack), then led his cavalry out of the city and, fearing neither the numbers nor the aggressiveness of the enemy, firmly held his ground against their first onslaught and brought the rapid assault on the wall to a halt. When raw levies were confronted by veteran troops; infantry by cavalry; undisciplined individuals by military cohesion; lightly armed men by fully armed legionaries; men attending more to rage than to forethought, by obedient men doing everything by the command of a leader — the Jews were easily defeated. When once the front ranks of the attackers were broken by the cavalry, they turned tail; and running into those in back who were pushing them towards the wall, they became their own enemies, until the entire mass gave way before the cavalry charges and scattered all over the plain. This was very large and ideal for cavalry tactics, a fact which weighted the scales in favor of the Romans and led to frightful carnage on the Jewish side. |

| Nam et fugientes prævertendo, cursum in eos flectebant ; et quos occupassent, curriculo transfigendo infinitos peremere. Alii vero alios, quocunque se vertissent circumdatos, exagitantes facile jaculis opprimebant. Et Judæis quidem propria multitudo, per desperationem salutis, solitudo videbatur ; Romani vero, licet ad pugnam pauci essent, rebus tamen secundis animati, etiam superfluere se putabant. Et illi quidem res adversas superare certantes, dum pudet cito fugere, mutari fortunam sperant ; Romani autem, in his quæ prospere agerent minime delassati, ad majorem usque diei partem pugnam protrahunt ; donec Judæorum quidem perempta sunt X• milia, duoque duces Joannes et Silas ; ceteri vero plerique saucii, cum Nigro qui unus restabat ex ducibus, in oppidum Idumææ, quod Salis dicitur, confugere. Nonnulli tamen etiam Romanorum in illo prœlio vulnerati sunt. |

For, overtaking the fleeing men, they charged them and, by running them through at a gallop, killed vast numbers of those they had cut off. Whichever way they turned, other Romans encircled others of them, chasing them about, and easily struck them down with javelins. Indeed, because of their hopeless state, to the Jews their own very numbers seemed isolation, whereas the Romans, even though they were few in the fight, were so energized by their success that they even thought their numbers excessive. The Jews battled against their reverses, ashamed of their swift defeat and hoping for a change of fortune; the Romans, on the other hand, not at all tiring in what they were doing with such success, continued the fight until the end of the day, by which time 10,000 Jewish soldiers had fallen with two of their commanders, John and Silas. The survivors, wounded for the most part, with one general left, Niger, fled to a little town in Idumæa called Salis. Roman casualties in this encounter amounted to a few men wounded. |

| 3 |

| Sed non Judæorum spiritus clade tanta sedatus est, multoque magis eorum dolor incitavit audaciam, et contemnentes quantum ante pedes mortuorum jaceret, pristinis rebus feliciter gestis ad cladem alteram illiciebantur. Denique parvo tempore intermisso, quod ne curandis quidem vulneribus satis esset, cunctisque aggregatis viribus, majore cum indignatione multoque plures Ascalonem recurrebant, eadem se, præter imperitiam aliaque belli vitia, comitante Fortuna. |

Far from the spirits of the Jews being broken by such a disaster, their suffering incited their determination even more, and, disregarding how many of the dead lay at their feet, they were lured by their earlier successes to a second disaster. After a short pause not even long enough for their wounds to heal, they mustered all their forces and with greater fury than before, and much greater numbers, ran back to Ascalon. But together with their inexperience and other military deficiencies, the same ill Fate went with them. |

| Etenim quum Antonius qua transituri fuerant posuisset insidias, ex improviso in eas delapsi et ab equitibus circumdati, priusquam se ad pugnam componerent, iterum super VIII• milia procubuerunt ; ceteri vero omnes aufugerunt ; cumque his Niger, multis dum fugeret magni animi facinoribus demonstratis ; et quoniam hostes instarent, in turrim quandam tutissimam compelluntur cujusdam vici, cui nomen est Bezedel. |

For Antonius laid ambushes in the passes, so that they fell unexpectedly into these traps, were encircled by the cavalry before they could get ready for battle and again lost over 8,000. All the rest fled, including Niger, who during the flight gave many proofs of his heroism. With the enemy on their heels, they were driven into a strong tower in a village called Bezedel. |

| Antonius vero cum suis, ne vel moras circum turrim, quæ inexpugnabilis esset, diu tererent, vel ducem hostium fortissimum vivum relinquerent, ignem muro supponunt, turrique inflammata, Romani quidem exsultantes recedunt, quasi etiam Nigro consumpto ; ille autem in castelli specus intimum ex turri saltu demissus evasit ; triduoque post sociis cum fletu eum ad sepulturam investigantibus sese ostendit, gaudioque insperato replevit omnes Judæos, tanquam Dei providentia dux eis in posterum servatus. |

Antonius and his men, to avoid wasting time around an almost impregnable tower, or else leaving the enemy’s heroic commander alive, lit a fire at the foot of the wall. With the fort ablaze, the Romans withdrew triumphantly, assuming that Niger had perished with it. But he had escaped by leaping down from the tower and into a cave in the very center of the fort. Three days later while his comrades, seeking his body in order to bury it, were lamenting aloud, he appeared, and joy undreamed-of filled all the Jews, as though the providence of God had preserved him to lead them in the future. |

| 4 |

| At Vespasianus Antiochiam, exercitu adducto (quæ Syriæ metropolis est, magnitudine simul aliaque felicitate sine dubio tertium inter omnes quæ in Romanorum orbe sunt locum obtinens) ubi etiam adventum suum regem Agrippam omni manu propria offenderat præstolari, ad Ptolemaidem properabat. In hac autem civitate occurrerunt ei Sepphoritæ cives oppidum Galilææ colentes, soli mente pacata. Qui tam suæ salutis providentia soliciti, quam Romanorum virium gnari, etiam priusquam Vespasianus veniret, Cestio Gallo fidem dederant, dextrasque junxerant, præsidiumque militare susceperant, tunc quoque benignissime duce suscepto, alacri animo etiam contra gentiles suos auxilia promiserunt. Quibus interim Vespasianus præsidii causa poscentibus, equitum peditumque tantum numerum tradidit, quantum obstare posse arbitrabatur incursibus, si quid Judæi commovere temptassent. Non enim minimum esse videbatur futuri belli periculum, auferri civitatem Sepphorim Galilææ maximam et in loco tutissimo conditam, totiusque gentis futuram præsidio. |

But Vespasian, after having taken his army to Antioch — the capital of Syria and by virtue of its size and prosperity undoubtedly the third city of the Roman Empire — where he had found King Agrippa awaiting his arrival with the whole of his own army, advanced swiftly to Ptolemais. There he was met by the inhabitants of Sepphoris, a town of Galilee, the only ones who desired peace. With their own safety and Roman supremacy in mind, even before Vespasian arrived they had pledged their loyalty to Cestius Gallus, sealed it by handshake, and admitted a garrison. Now they gave an enthusiastic reception to the commander and eagerly promised their help against their own countrymen. In response to their request for a garrison, he allotted them only as large a number of horse and foot as he though adequate to defeat any incursions if the Jews should try to perpetrate anything; for he thought it would be no small danger in the coming war to lose Sepphoris, the largest city in Galilee, sited in a very safe location, and which would serve as a bulwark of the whole nation. |

|

| ⇑ § III |

Descriptio Galilææ, Samariæ,

et Judææ. | A description of Galilee, Samaria and Judæa. |

|

| 1 |

— Caput C-2 —

Descriptio Galilææ, Samariæ et Judææ. |

| Duæ sunt autem Galilææ, quæ Superior et Inferior appellantur, easque Phœnice et Syria cingunt. Discernit vero ab Occidente Ptolemais territorii sui finibus, et quondam Galilæorum, nunc autem Tyriorum mons Carmelus ; cui conjuncta est Gaba, « Civitas Equitum », quæ sic appellatur eo quod equites ab Herode rege dimissi, coloni eo deducebantur. A meridie autem Samaritis et Scythopolis, usque ad flumen Jordanem. Ab Oriente vero Hippene et Gadaris, sed et Gaulanitidis definit, qui etiam regni Agrippæ fines sunt. Septentrionalis autem ejus tractus Tyro, itemque Tyriorum finibus terminatur. Inferioris quidem Galilææ longitudo a Tiberiade usque ad Zabulon, cui vicina est in locis maritimis Ptolemais, protenditur. Latitudine autem patet a vico Xaloth, qui in Magno Campo situs est, usque ad Bersaben ; unde etiam Superioris Galilææ latitudo incipit usque ad Baca vicum, qui terram dirimit Tyriorum. Longitudo vero ejus a Thella vico Jordani proximo usque ad Meroth extenditur. |

There are two Galilees, known as Upper and Lower, shut in by Phœnicia and Syria. They are bounded on the west by Ptolemais with its border region and Carmel, a mountain that once belonged to Galilee but now belongs to Tyre; adjoining Carmel is Gaba, known as “Cavalry Town” because King Herod’s cavalry settled there on their discharge. The southern limit is formed by Samaritis and Scythopolis as far as the streams of Jordan, the eastern by the districts of Hippus, Gadara and Gaulanitis, where Agrippa’s kingdom begins. Beyond the northern frontier lie Tyre and the Tyrian lands. Lower Galilee stretches in length {(E ⇛ W)} from Tiberias to Zebulon, the neighbor of Ptolemais on the coast, in breadth {(S ⇛ N)} from the village of Xaloth in the Great Plain to Bersabe. Here begins Upper Galilee, which stretches in width as far as Baca, a village on the Tyrian frontier; in length it extends from Thella, a village near the Jordan, to Meroth. |

| 2 |

| Sed quum tanta sint utræque magnitudine, tantisque gentibus alienigenis cinctæ, semper tamen omnibus belli periculis restiterunt. Nam et pugnaces sunt ab infantia Galilæi, et omni tempore plurimi, neque aut formido unquam viros, aut eorum penuria regiones illas occupavit ; quoniam totæ optimæ ac fertiles sunt, omniumque generum arboribus consitæ, ut etiam minime agriculturæ studiosos ubertate sua provocent ; denique excultæ sunt ab incolis totæ, nec pars ulla est earum otiosa ; quin et civitates ibi crebræ sunt, et ubique multitudo vicorum propter opulentiam populosa, ut qui sit minimus, supra quindecim milia colonorum habeat. |

But while both are of such size and encircled by such great foreign peoples, the two Galilees have invariably held out against enemy attack; for the Galileans are fighters from the cradle and at all times numerous, and cowardice has never afflicted the men or lack of them, the country. For the whole area is rich and fertile, planted with all types of trees, so that by its richness it appeals even to those least interested in farming. Consequently every inch has been cultivated by the inhabitants and no part of it lies idle. There are many, many towns there, and thanks to its bounty the innumerable villages are so populous that the smallest has over 15,000 inhabitants. |

| 3 |

| Prorsus, ut etiamsi quis magnitudine minorem Galilæam dixerit quam trans fluvium regionem, viribus tamen eam prætulerit. Hæc enim universa colitur, tota fructuum ferax ; at illa quæ trans flumen est, licet multo major sit, pleraque tamen aspera atque deserta est, et nutriendis fructibus mansuetis inhabilis. Perææ sane mollities et ingenium fructuosum, campos habet cum variis arboribus consitos, tum maxime olivetis ac vineis et palmetis excultos. Irrigatur autem abunde montanis torrentibus, et fontibus aquæ perennis, quoties illi Sirio æstuante defecerint. Et longitudo quidem ejus est a Machrærunte in Pellam ; latitudo vero a Philadelphia usque ad Jordanem. Et Pella quidem, quam supra diximus, septentrionalis ejus est tractus ; occiduus vero Jordanis ; meridianum autem Moabitis regio terminat ; ab oriente autem Arabia et Silbonitide, necnon et Philadelphia, itemque Gerasis clauditur. |

In short, as even if someone may say that Galilee is smaller in size than the region across the river, he will still give it preeminence in productivity; for the whole country is cultivated and fruitful everywhere, but what is across the river, even though much larger, is nonetheless mostly rough and desert, and unsuited to producing domesticated crops. On the other hand, Peræa’s workable soil and fruitful quality offer plains planted with various trees, growing especially olive trees and vineyards and palms. The country is abundantly watered by mountain torrents — and by perennial springs whenever the former sources dry up in the dog days {(July 23-Aug 23)}. In length {(S ⇛ N)} it stretches from Machærus to Pella, in breadth {(E ⇛ W)} from Philadelphia to the Jordan. Pella, just mentioned, forms the northern boundary, Jordan the western; the southern limit is Moab, and on the east it is bounded by Arabia and Silbonitis as well as by Philadelphia and likewise Gerasa. |

| 4 |

| Samariensis autem regio inter Judæam quidem et Galilæam sita est ; incipiens enim a vico in Planitie posito, cui nomen est Ginæa, in Acrabatenam desinit toparchiam ; sed natura nihil a Judæa discrepat. Nam utræque montosæ sunt et campestres, agrosque colendo molles atque optimæ, necnon et arboribus plenæ ; pomisque tam silvestribus quam mansuetis abundant, eo quod natura sunt aridæ, imbriumque satis habent. Dulces autem per eas supra modum aquæ sunt, bonique graminis copia præter alias earum pecora lactis abundant ; quodque maximum virtutis atque opulentiæ specimen est, utraque viris referta est. |

The Samaritan territory lies between Galilee and Judæa; beginning at a village in the Great Plain called Ginæa, it ends at the prefecture of Acrabata. In character it does not differ at all from Judæa: both are made up of hills and plains, fine and easy for field cultivation. In addition they are well wooded and prolific in fruit both wild and domesticated because they are naturally dry and yet have enough rain. Their streams are extraordinarily sweet, and due to the abundance of lush grass the milk-yield of their cows is greater than elsewhere. The final proof of their outstanding productivity is that both are teeming with people. |

| 5 |

| Harum confinium est Anuath vicus, qui etiam « Borceos » appellatur, Judææ limes a septentrione. Meridiana vero pars ejus, si in longitudinem metiare, adjacenti vico Arabum finibus terminatur, cui nomen est Jarda. Latitudo sane a Jordane flumine usque ad Joppem explicatur. Media vero ejus est Hierosolyma ; unde quidam, non sine ratione, umbilicum ejus terræ eam urbem vocaverunt. Sed nec marinis quidem Judæa deliciis caret, ad Ptolemaidem usque locis extenta maritimis. In undecim autem sortes divisa est ; quarum prima est tanquam regia Hierosolyma, præ ceteris inter omnes accolas eminens, velut caput in corpore. Aliis vero post hanc toparchiæ sunt distributæ. Gophna est secunda, et post eam Acrabata. Ad hoc Tamna, et Lydda, itemque Ammaus, et Pella, et Idumæa, et Engadda, et Herodium, et Hiericus ; deinde Jamnia et Joppe finitimis præsunt, et præter has Gamalitica, et Gaulanitis, et Batanæa, et Trachonitis ; quæ etiam regni Agrippæ partes sunt. Eadem vero terra incipiens a monte Libano et fontibus Jordanis, usque ad Tiberiadi proximum lacum latitudine panditur. A vico autem qui appellatur Arphas ad Juliada oppidum longitudine tendit ; et habitatur ab incolis Judæis Syrisque permixtis. |

On their common boundary lies the village of Anwath, also called “Borceos,” the limit of Judæa on the north. The southern region, if you were to measure lengthwise {(N ⇛ S)}, is terminated by a village named Jarda adjacent to the Arab borders,. In breadth {(E ⇛ W)} it stretches from the River Jordan to Joppa. Its middle is the City of Jerusalem, so that some have, not unreasonably, called her the navel of that country. Moreover, Judæa does not want for seaside amenities, given that it extends coastally all the way to Ptolemais. It is divided into eleven allotments, of which the first — as though the royal one —, Jerusalem, rises above all others among the neighbors as the head above the body. The prefectures are distributed to other allotments, secondary to this one. Gophna ranks second, followed by Acrabata, Thamna, Lydda, Emmaus, Pella, Idumæa, Engedi, Herodium and Jericho. Then Jamnia and Joppa come before the last ones, and besides these the Gamala district and Gaulanitis, Batanæa and Trachonitis which are parts of Agrippa’s kingdom. That same territory begins at Mount Lebanon and the sources of the Jordan, and in width {(N ⇛ S)} stretches to the lake next to Tiberias, in length {(E ⇛ W)} from a village called Arpha to the town of Julias. The population is a mixture of Jews and Syrians. |

— Caput C-3 —

De auxilio Sepphoris misso, et Romanorum disciplina militari. |

| De Judæa quidem, et quibus esset cincta regionibus, quam maxime potui breviter exposui. |

I have now given a description, as brief as possible, of Judæa and the regions surrounding it. |

|

| ⇑ § IV |

Josephus, facta impressione

in Sepphorin, repulsus est.

Titus cum ingenti exercitu

Ptolemaïdem venit. | Josephus makes an attempt upon Sepphoris but is repelled. Titus comes with a great army to Ptolemais. |

| 1 |

| QUOD autem Vespasianus miserat auxilium Sepphoritis — hoc est, equites mille sexque milia peditum, Placido eos regente tribuno —, castris in Magno Campo positis bifariam dividuntur. Et pedites quidem in civitate, ipsius tuendæ causa, equitatus vero in castris, degebat. Utrimque autem assidue prodeundo, et circa eam regionem loca omnia incursando, magnis incommodis Josephum ejusque socios, quamvis quietos, afficiebant. Et præterea civitates extrinsecus deprædabantur, civiumque conatus, si quando excurrendi habuissent fiduciam, repellebant. Josephus tamen adversus civitatem impetum fecit, sperans eam posse capere — quam ipse, antequam a Galilæis deficeret, ita muris cinxerat, ut Romanis quoque esset invicta. Unde etiam spe frustratus est, quum nec vi nec suasu Sepphoritas in suas partes pertrahere potuisset ; magisque in Judæa bellum accendit, Romanis indigne ferentibus insidias, et propterea nec die nec nocte ab agrorum depopulatione cessantibus, sed passim diripientibus quicquid rerum in his repperissent ; qui tamen, quum mortem pugnacibus semper inferrent, imbelles ad servitium capiebant ; ignis vero et sanguis Galilæam totam repleverat, nec quisquam expers ejus acerbitatis aut cladis erat. Unam salutis spem fugientes habebant in civitatibus, quas murorum ambitu Josephus communierat. |

The support that Vespasian sent to Sepphoris consisted of 1,000 horse and 6,000 foot, commanded by the tribune Placidus. After camping in the Great Plain, the force divided, the foot moving into the city as a garrison and the horse remaining encamped outside. Constantly sallying forth from both places, and overrunning the whole district, they did great damage to Josephus and his men, no matter how unprovocative they were. And besides that they pillaged the cities outside the area and beat back the attempts of the city people, if they sometimes had the courage to sally forth. Josephus, in the hope of capturing it, actually made a attack on the city which he himself, before it seceded from the Galilæans, had girded with a wall so strongly that it would have been impregnable even to the Romans. And so he was frustrated in his hope since he had been unable to draw the Sepphorites over to his side either by force or by persuasion. Moreover, he inflamed the war in Judea all the more, with the Romans enraged at his ambushes and so night and day ceaselessly ravaging the plains and plundering whatever they found in them; they killed everyone who fought back and enslaved those unable to fight. Indeed, fire and blood filled all of Galilee; there was no one who did not experience its bitterness or disaster. The only hope of safety for the fugitive inhabitants was in the towns which Josephus had fortified with a surrounding wall. |

| 2 |

| Titus autem, Alexandriam transmissus ex Achaja citius quam per hiemem sperabatur, manum militum cujus causa missus fuerat suscepit ; contentoque usus itinere, mature ad Ptolemaidem pervenit. Quumque ibi patrem suum repperisset, duabus quas secum habebat legionibus (erant autem nobilissimæ Quinta et Decima) junxit etiam quam ille adduxit Quintamdecimam. Eas autem sequebantur decem et octo cohortes ; quibus accessere ex Cæsarea quinque cum una ala equitum, et alæ quinque Syrorum equitum. Decem autem cohortium singulæ mille pedites habebant ; in ceteris vero tredecim, sescenti pedites, et centeni viceni equites erant. Satis autem auxiliorum etiam a regibus congregatum est. Antiochus enim et Agrippa et Sohemus bina milia peditum, et sagittarios equites mille præbuerunt. Quum Arabiæ quoque est Malchus : præter quinque milia peditum, equites mille misisset, quorum pars major erant sagittarii ; ut tota manus computata cum regiis, sexaginta milia circiter peditum equitumque colligeret, præter calones qui plurimi sequebantur et meditationi bellicæ assueti nihil a pugnacissimis aberant ; quod tempore quidem pacis dominorum exercitationibus interessent, belli autem pericula cum ipsis experirentur, et neque peritia, neque viribus a quoquam nisi a dominis vincerentur. |

Titus, meanwhile, had sailed from Greece faster than expected in wintertime to Alexandria where he took over the force for which he had been sent and, by forced march, quickly reached Ptolemais. There he found his father, and to the two legions that accompanied him — the world-famous Fifth and Tenth — he united his father’s Fifteenth. Eighteen cohorts followed them; they were also joined by five cohorts with one cavalry squadron from Cæsarea plus five squadrons of Syrian cavalry. Of the cohorts, ten had 1,000 infantry each; the other thirteen were composed of 600 infantry and 120 cavalry apiece. A considerable force of auxiliaries was gotten together by the kings: Antiochus, Agrippa and Sohemus each provided 2,000 infantrymen and 1,000 mounted archers. While there is also Malchus of Arabia: besides 5,000 infantrymen, he sent 1,000 cavalry, of which the greater part was archers. So that the whole force, reckoned together with the kings’ militaries, amounted to about 60,000 infantry and cavalry, apart from the servants who followed in great numbers and who, habituated to military drill, do not differ in the least from the most combative fighters — since in peacetime they participate in their masters’ exercises, in war they share their dangers, and in skill and prowess are surpassed by none but their masters. |

|

| ⇑ § V |

Descriptio Romanorum

exercituum, et castrorum,

aliorumque, propter quæ

laudantur Romani. | A description of the Roman armies and Roman camps and of other particulars for which the Romans are commended. |

| 1 |

| Qua quidem in re nimis admirandam quis existimaverit Romanorum providentiam, ita servos instituentium, ut non solum vitæ ministerio, sed belli etiam necessitatibus utiles sint. Quod si quis eorum aliam quoque respexerit militiæ disciplinam, profecto cognoscet tantum eos imperium non fortunæ munere, sed propria virtute quæsisse. Armis enim uti non in bello incipiunt, neque solum, si necesse sit, manus movent, quum in pacis otio cessaverint, sed armis veluti natura cohærentes, nullas capiunt exercitationis indutias, nec tempora præstolantur. Meditationes autem eorum nihil a vera contentione discrepant, sed in dies singulos militum quisque omnibus armis, tanquam in procinctu positus, exercetur, quo etiam facillime prœlia tolerant. Neque enim ordo neglectus eos a consueta dispositione dispergit, neque metus stupefacit, neque lassitudo exhaurit. Unde sequitur, ut semper superent quos non itidem confirmatos invenerint. Nec erraverit si quis eorum meditationes conflictus esse dixerit sine sanguine, contraque prœlia meditationes cum sanguine. |

Anyone who considers it will find the foresight of the Romans in this matter truly amazing — the way they instruct their slaves to be useful not only in the management of life, but even in the emergencies of war. But if one studies the organization of their army, he will certainly recognize that they have acquired their vast empire through their own dynamism, not as the gift of fortune. They do not wait for war before first using arms, or start moving only in a crisis, while stagnating during the calm of peacetime; but as if endowed with arms by nature they never take time out from training or wait for the proper time. In no way do their battle-drills differ from real combat; every man works as hard at his daily training as if he were on the battlefield, which is also why they so easily endure battles: no indiscipline dislodges them from their regular formation, no panic paralyzes them, no weariness exhausts them; so victory over men not so trained follows as a matter of course. It would not be far from the truth to call their drills bloodless battles, the battles bloody drills. |

| Nam ne repentino quidem hostium incursu opprimi possunt, sed quocunque in hostilem terram irruperint, non nisi permunitis castris prœlio decernunt. Quæ quidem non levi opere, nec iniquo loco erigunt, nec inordinate describunt, sed si quidem inæquale solum fuerit, complanatur ; quattuor vero angulis horum dimensio designatur. Nam fabrorum multitudo, et ferramentorum copia quæ usus exstructionis postulat, sequitur exercitum. |

They can not be overcome even by a sudden enemy attack; for wherever they invade hostile territory they do not commit to battle until after having fortified their camp. This they do not construct sloppily or on uneven ground, nor do they design it in a disorderly manner, but if the ground is uneven, it is thoroughly levelled, then its layout is marked out as a rectangle. To this end the army is followed by a large number of engineers with all the tools needed for building. |

| 2 |

| Et interior quidem pars castrorum tabernaculis distribuitur, ambitus autem eorum extrinsecus muri faciem præfert, ordinatis etiam turribus pari spatio dispositis, quarum intervalla catapultis atque ballistis, et aliis machinis saxa intorquentibus omnibusque instrumentis missilium complent, ut cuncta scilicet jaculorum genera in promptu sint. Portas autem quattuor ædificant, tam jumentis aditu faciles, quam ipsis, si quid urgeat, intro currentibus latas. Intus autem castra vici spatiis interpositis dirimunt, mediaque rectorum tabernacula collocant, et inter hæc prætorium divum templo simillimum, prorsus ut quasi repentina quædam civitas exsistat ; forum quoque et opificum stationes, et sedes militum primatibus, ordinumque principibus, ubi si qua sit inter alios ambiguitas judicent. Ipse vero ambitus, omnia quæ in eo sunt, multitudine simul et scientia fabricantium opinione citius communitur. Qui, si res urgeat, fossa extrinsecus cingitur, depressa cubitis quattuor, parique spatio lata. |

The inside of the camp is divided up for tents. From outside the perimeter looks like a wall and is equipped with evenly spaced towers. They fill the gaps between the towers with catapults, ballistas and other rock-slinging machines and every sort of projectile thrower, so that all kinds of artillery are ready for use. They build four gates, both practicable for the entry of baggage-animals and wide enough for themselves to run in through if need be. Inside, spaced streets intersect the camp; in the middle the officers’ tents are erected, and among these the commander’s headquarters, which resembles a shrine. It all seems like some instant town, with market-place, workmen’s quarters and courtrooms of military officers and heads of the ranks where, among other things, they may sit in judgement on any disputes that may arise. The erection of the outer wall and the buildings inside is accomplished faster than one would expect, thanks to the number and skill of the workers. If necessary, a ditch is dug all around, six feet deep and the same width. |

| 3 |

| Armis autem sæpti, per contubernia cum decore atque otio in tentoriis agunt, omniaque ab his ordinate etiam alia, cauteque, per contubernia expediuntur, veluti si ligno aquave opus sit aut frumento ; nec enim cena vel prandium quum voluerit, in potestate cujusque est ; simul autem omnibus somnus est, excubias et vigilandi tempora buccinæ significant, neque est omnino quicquam quod sine edicto geratur. Mane autem milites quidem ad centuriones, illi vero ad tribunos conveniunt salutatum ; cum quibus ad summum omnium ducem universi ordinum principes. Ille autem his signum aliaque dat ex more præcepta proferenda subjectis. Quibus etiam in acie circumaguntur quo opus est, ac universi pariter incurrunt itemque sese recipiunt. |

After having been shielded with armed fortifications, they lodge in the tents with seemliness and calm by platoons. All other duties too are carried out by the platoons in a disciplined way and with attention to security, as when they need wood or water, or grain. Having supper or lunch when they want is not at their individual discretion. Sleep is at the same time for everyone; trumpets signal guard duties and times for reveille, and nothing whatever is done without orders. At dawn the soldiers convene to salute their centurions, the centurions their tribunes, then the superior officers go with them to salute the commander-in-chief. In accordance with routine, he gives them the password and other orders to communicate to their subordinates. By means of such techniques they are also directed around where needed on the battlefield, and they all advance and retreat as a unit. |

| 4 |

| Quum autem castris egrediendum est, tuba indicium facit ; nemoque otiosus est, sed vel solo nutu moniti, tabernacula tollunt, omniaque ad profectionem instruunt. Deinde iterum tuba ut sint parati significat. Illi autem quum mulos et jumenta sarcinis oneraverint, velut in curuli certamine signum expectant. Castra vero incendunt, eo quod sibi alia munire facile sit, et ne quando hostibus eadem usui sint. Et tamen tertio quoque tubæ signo indicant ut exeatur, urgendo aliqua ex causa morantes, ne quis ordinem deserat. Dexterque duci præco astans, si ad bellum parati sunt, voce patria ter percontatur. Illique toties alacri et magna voce paratos esse se respondent, interrogantemque præveniunt ; et Martio quodam spiritu repleti cum clamore dextras erigunt. |

When it is time to break camp, the trumpet sounds; no one remains idle, but at just the mere hint of a signal the tents are taken up and all preparations made for departure. The trumpet then sounds a second time to get ready. After loading the mules and pack animals with baggage, they wait for the signal as though in a race competition. Indeed, they set fire to the camp, since it is easy to construct another one, and so that it will not some day be useful to the enemy. For the third time the trumpets give the signal for departure, to urge on those who for any reason have been delayed, so that no one will be missing from his place. Then the announcer, standing on the right of the general, asks three times in their native language whether they are ready for war. Just as many times they shout back energetically and with enthusiasm, “Ready!” — also answering even before the question and, filled with a kind of martial fervor, raising their right arms as they shout. |

| 5 |

| Deinde otiose et cum omni decore progredientes ambulant, suum quisque ordinem velut in bello custodiens. |

Then they step off, all marching smoothly and in good order, every man keeping his place in the column as if off to battle. |

- Pedites quidem thoracibus et galeis sæpti, et utroque latere gladiis accincti. Lævus autem gladius multo est longior, quum dexter mensuram palmæ non excedat. Qui vero ducem stipant lecti pedites, scuta et lanceas gestant ; cetera manus hastas et clipeos longos, serramque et corbem et sarculum et securim, necnon et habenam et falcem et catenam, triduique viaticum, ut parum intersit inter onusta jumenta et pedites.

|

- The infantryman is armored with breastplate and helmet, and is girded with a blade on each side; of these, by far the longer is the one on the left, the right one being no more than nine inches long. The elite infantrymen escorting the general carry rectangular shields and spears, the other units javelins and long oval shields, together with saw and basket, a hand hoe and axe, as well as a strap, sickle, chain and three days’ rations, so that there is not much difference between pack animals and foot-soldiers!

|

- Equitibus autem ad dexteram gladius est longior, et contus in manu, transversusque ad equi latus clipeus, ternaque in pharetra vel amplius dependent lata cuspide jacula, nihil ab hastis magnitudine differentia. Cassides vero et thoracas peditibus habent similes ; nulloque armorum genere ab equitum alis discrepant lecti qui circum ducem versantur.

|

- The cavalryman carries a longer sword on his right and a long pike in his hand, an oval shield slanted across his horse’s flank and, in a quiver slung alongside, three or more missiles, broad-pointed and no different than javelins in size. They have helmets and breastplates similar to those of the infantry. In none of their arms do the elites surrounding the general differ from the cavalry squadrons.

|

| Agmina autem, semper cui sorte id obtigerit, antecedit. |

Lots are always drawn for the legion that is to head the column. |

| 6 |

| Talia quidem sunt Romanorum itinera et mansiones, itemque armorum varietas. Nihil vero nec in prœliis inconsultum aut subitum agunt, sed omnia semper sequuntur facta sententiam, opusque adhibetur ante decretis. Unde aut minime peccant, aut si peccaverint, facilis est errati correctio. Fortunæ autem successibus meliores consiliorum — etiamsi aliter successerit — arbitrantur eventus ; quasi bonum quidem fortuitum ad rem inconsulte gerendam illiciat ; quæ vero ante cogitata fuerint, etiamsi adversus casus exceperit, bene jam meditatos exhibeant ad cavendum ne idem rursus eveniat ; et bonorum quidem fortuitorum non is auctor si cui contigerint, tristium vero quæ præter sententiam acciderint, saltem recte consulta videantur esse solatium. |

So much for Roman routine on the march and in quarters, and for the variety of equipment. In battle nothing is done without plan or on the spur of the moment; all actions always follow forethought, and operations implement what is preplanned. As a result they make few errors, and if they do make a mistake, the errors are easily corrected. They regard the outcomes of planning better than successes due to luck — even if the outcome is different, because a fortuitous victory tempts men to improvident actions, but predeliberation, even if a failure results from it, shows those who carefully think it over how to beware of having the same thing happen again. And the man to whom fortuitous victories happen is not their author; on the other hand, the man to whom fortuitous defeat happens despite forethought, at least has the consolation that things seem to have been properly planned. |

| 7 |

| Armorum quidem exercitatione comparant ut non modo corpora, sed animi quoque militum fortiores sint. Major autem illis est ex timore diligentia. Namque leges apud eos non desertionis solum, verumetiam minimæ neglegentiæ sunt capitales ; ducesque magis quam ipsæ leges terribiles ; namque bonos honorando redimunt ne in coërcendis noxiis videantur crudeles. Tanto autem obsequio rectoribus parent, ut et in pace ornamento sint, et in acie corpus unum totius conspiciatur exercitus. Sic eorum copulati sunt ordines, ita circumduci sunt mobiles ; et acutis auribus ad præcepta, oculisque ad signa, et ad opera manibus ; unde facere quidem semper strenui sunt, pati vero tardissimi. |

Military exercises give the Roman soldiers not only tough bodies but determined spirits as well. Greater scrupulousness is instilled in them by fear; for military law demands the death penalty not only for desertion but even for trivial negligence; and the generals are more feared than the laws themselves, for by honoring good soldiers they offset seeming cruel in punishing delinquents. They obey their officers with such submission that they constitute an adornament in peacetime and in war it impresses one as a single body of the whole army; with their ranks so welded together, they are maneuverable when being directed around — and with ready their ears for orders, their eyes for signals, their hands for tasks to be done. Thus it is that they are always prompt in acting, but very slow to suffer. |

| Nec est ubi prœliantes aut multitudinem hostium aut consilia sensere ducum, aut difficultatem regionum ; sed ne fortunæ quidem succubuere. Nam in ea {(i.e., disciplina)} certiorem putant esse victoriam. Quorum igitur actus a consiliis incipiunt, consultaque adeo strenuus exsequitur exercitus, quid mirum si Euphrates ab oriente, et Oceanus ab occidente, itemque a meridiano tractu Africæ fertilissima regio, et a septentrione Rhenus atque Danubius sunt Imperii limites, quum minorem esse possidentibus possessionem, recte quis dixerit ? |

There is also no place where in fighting they have been affected by either the vast numbers of the enemy or the ruses of their leaders or the difficulties of the terrain; nor have they succumbed even to luck. For in that {(i.e., disciplined system)} they think victory is surer than luck. When planning goes before action, and the plans are followed out by such a vigorous army, is it any wonder that in the east the Euphrates, in the west the ocean, in the south the richest plains of Africa, and in the north the Danube and the Rhine are the limits of the Empire? One might say with truth that the conquests are less remarkable than the conquerors. |

| 8 |

| Hæc ergo prosecutus sum, non tam proposito laudandi Romanos, quam solatio devictorum, et ut novarum rerum cupidos deterrerem ; fortasse autem et ad experientiam proderunt bonarum artium studiosis, Romanæ instituta militiæ nescientibus ; redeo tamen unde digressus sum. |

The purpose of the foregoing account has been less to eulogize the Romans than to console their defeated enemies and to deter any who may be thinking of revolt; and it may possibly be of educational benefit to students of culture who are unaware of the Roman military setup. I now return to where I left off. |

|

| ⇑ § VI |

Placidus, tentatis oppugnatione

Jotapatis, repellitur. Vespasianus

impressionem facit in Galilæam. | Placidus attempts to take Jotapata and is beaten off. Vespasian marches into Galilee. |

| 1 |

— Caput C-4 —

Impetus Placidi adversus Jotapatam. |

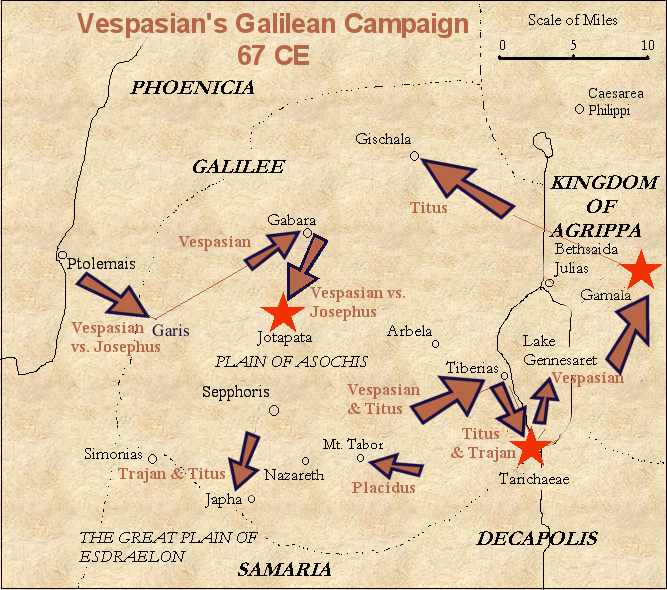

| Vespasianus quidem una cum Tito filio in Ptolemaide interim degens, ordinabat exercitum. At vero Galilæam pervaserat Placidus, ubi maximam eorum quos comprehendisset multitudinem interemit ; hæc autem fuit Galilæorum imbellior turba, animisque deficiens ; pugnacissimos autem ut vidit semper in civitates confugere quas Josephus communierat, in Jotapatam, quæ omnium tutissima erat, impetum vertit, existimans eam repentino aggressu facillime captum iri, magnamque et sibi ex ea re alios apud rectores gloriam comparandam, et illis commodum ad reliqua maturius explicanda, quasi metu cessuris aliis civitatibus, si quæ validissima esset occupatam vidissent. |

Meanwhile Vespasian, together with his son Titus, was at Ptolemais organizing his forces. Placidus, on the other hand, had swept through Galilee where he destroyed great numbers of men who had fallen into his hands, these being the less warlike members of the Galilæans and the faint of heart. Then, seeing that the most combative regularly took shelter in the towns that Josephus had fortified, he turned to attack the strongest of them, Jotapata, thinking it would be easily captured in a surprise assault, and he would thereby achieve great glory for himself among the other commanders. Plus, it would be helpful to them in quickly finishing off everything else, for the other towns would surrender out of fear once they had seen the most powerful one captured. |

| Multum tamen opinione deceptus est ; Jotapateni enim, quum ejus impetum præsensissent, prope civitatem advenientem excipiunt ; congressique cum Romanis ex improviso plurimi et ad pugnam parati, necnon et alacres (quippe ut pro salute patriæ, item conjugum liberorumque dimicantes) in fugam eos vertunt, multosque sauciant, septem solum interfectis ; quia neque inordinate pugna decesserant, sæptisque undique corporibus leviter fuerant vulnerati ; quum Judæi quoque magis eminus jaculari quam manus conserere inermes cum armatis confiderent. Ex ipsis autem Judæis tres ceciderunt, paucis præterea sauciatis. Placidus igitur ab oppido repulsus aufugit. |

But his hopes were completely dashed. As he approached Jotapata, its citizens, foreseeing his attack, laid an ambush near it and then pounced upon the unsuspecting Romans. With large numbers, ready for battle and quite zealous (for they were fighting for the safety of their country and of their wives and their children), they routed them, wounding many but killing only seven; for the Romans had not retreated from the fight in disorder and, being armored all over their bodies, had suffered only light wounds, while the lightly-armed Jews dared to launch their missiles only from a distance, rather than battling hand to hand with heavily armed men. On the Jewish side, three were killed and a few others were wounded. So Placidus, repulsed from the town, fled. |

| 2 |

— Caput C-5 —

Galilæa a Vespasiano invaditur. |

| Vespasianus vero ipse Galilæam cupiens invadere, ex Ptolemaide proficiscitur, ordinato militum itinere sicut Romani consueverunt. Auxiliatores enim qui levius armati essent itemque sagittarios præire jussit ad repentinos incursus hostium cohibendos, et ut suspectas atque opportunas insidiis silvas scrutarentur. Hos sequebatur Romani peditatus equitatusque pars ; post quos e singulis centuriis deni, armaturam suam ferentes mensurasque castrorum. Post hos stratores viarum ibant, qui aggeris maligna corrigerent, ac aspera complanarent, silvasque obstantes præciderent, ne perplexo itinere fatigaretur exercitus. |

Vespasian, eager to invade Galilee himself, set out from Ptolemais with his army arranged in the usual Roman marching order. He ordered the light-armed auxiliaries and archers to lead, to repel sudden enemy incursions and reconnoiter suspect woods ideal for ambushes. Next came part of the Roman infantry and cavalry. These were followed by ten men from every century carrying, besides their own kit, the instruments for marking out the campsite. After them came the roadbuilders to fix bad spots in the highway, level rough surfaces and cut down obstructive woods, so that the army would not be made weary by a difficult route. |

| Deinde suas itemque subjectorum sibi rectorum sarcinas, et tutelæ causa multos cum his equites ordinavit. Post quos ipse veniebat, lectos pedites equitesque, necnon et lancearios secum ducens, equitumque præterea suorum agmine comitatus. De singulis enim turmis proprios centum et viginti equites deputatos habebat. Hos sequebantur, qui expugnandis civitatibus machinas et cetera tormenta portarent, deinde rectores itemque præfecti cohortibus tribuni, stipati lectis militibus. Et post hos circum Aquilam signa alia, quæ omnibus apud Romanos agminibus præest, quod et universarum avium regnum habeat, et sit validissima. Itaque illam et principatus insigne putant, et omen victoriæ, quoscunque bello petierint. |

Following these he had his own personal baggage and that of his subordinate officers and a strong cavalry force to protect it. Behind them Vespasian himself rode, leading the cream of his horse and foot and a body of spearmen and accompanied besides by a cavalcade of his own legion’s cavalry. For he had 120 horsemen, assigned from each of the squadrons to which they belonged. These were followed by the transport of the machines for storming cities and of other artillery. After them came the generals and the tribunes heading the cohorts, escorted by picked troops. And behind them the various standards surrounding the eagle, which is at the head of all columns among the Romans, because it has supremacy over all birds and is the strongest of all: this they regard as the symbol of empire and portent of victory, no matter whom they war against. |

| Sacras vero signorum effigies sequebantur cornicines, et post eos acies, in latitudinem senis digesta militibus. Hisque adhærebat ex more quidam centurio, disciplinæ atque ordinis custos. Servi autem singularum legionum cuncti cum peditibus erant, mulis aliisque jumentis vehentes militum sarcinas. Postremum agmen, in quo erat mercennaria multitudo, cogebant armati pedites, equitumque non pauci. |

The sacred emblems were followed by the buglers, and in their wake came the main body, in width spread six men abreast, accompanied as always by a centurion to maintain discipline and the array. All the servants of the individual legions accompanied the infantry, carrying the soldiers’ baggage on mules and other beasts. The rear guard, in which there was a huge number of mercenaries {(probably part of the foreign auxiliaries, perhaps with non-combat logistics and support elements)}, was made up of armed infantry and quite a few cavalrymen. |

| 3 |

| Ita peracto itinere,Vespasianus cum omni exercitu ad fines Galilææ pervenit ; ibique positis castris, quamvis promptos ad bellum milites continebat, una et ostendendo exercitum, quo hostes metu percelleret, spatiumque indulgendo pænitudinis, si quis ante prœlium voluntatem mutaret ; nihilominus autem murorum instruebat obsidium. Itaque multos quidem rebelliones fugere vel solus fecit ducis aspectus ; metum vero universis incussit. Josephi enim socii, qui non longe a Sepphori castra posuerant ubi bellum appropinquare cognoverunt, et jam jamque Romanos prœlio secum congressuros, non modo ante pugnam, sed antequam hostes omnino conspicerent, fuga disjecti sunt. Cum paucis autem relictus Josephus, ubi animadvertit neque se ad excipiendos hostes sufficientem manum habere, et Judæorum animos concidisse, ac, si fides his haberetur, plerosque libenter ad hostes defectum ire, jam tum quidem bello omni abstinebat, quam longissime autem periculis abesse decrevit, abductisque qui secum remanserant in Tiberiada confugit. |

Marching in this way, Vespasian arrived with his whole army at the frontiers of Galilee. There he pitched his camp and restrained his soldiers, though they were eager for battle, both to strike fear into the enemy and to allow them a period for regret in case anyone wished to change his mind before battle; nonetheless, he set up preparations for besieging their strongholds. And indeed, the mere sight of the field marshal made many rebels flee; he truly struck fear into everyone. The troops of Josephus who had set up camp not far from Sepphoris, seeing the war approaching and the Romans about to close in combat with them, scattered — not just before a battle, but before they had even seen the enemy at all. Left behind with a handful of men, Josephus saw that he did not have enough of a force to stop the enemy, that the morale of the Jews had collapsed, and that, if their pledge were accepted, the majority would defect to the enemy. At that point, for the time being he avoided all conflict, and decided to keep as far away as possible from danger, and with those who had stuck to him sought shelter in Tiberias. |

|

| ⇑ § VII |

Vespasianus, capta Gadarensium

civitate, Jotapata proficiscitur :

et, post longam obsidionem,

urbem a transfuga proditam capit. | Vespasian, When He Had Taken the City Gadara, Marches to Jotapata. After a Long Siege the City Is Betrayed by a Deserter, and Taken by Vespasian. |

|

| 1 |

— Caput C-6 —

Gadaræ expugnatio. |

| Vespasianus autem Gadarensium civitatem aggressus, primo impetu capit, quod eam pugnaci multitudine vacuam repperisset. Deinde hinc transgressus interius, cunctos puberes interfecit, quum Romanos odio gentis, et cladis memoria quam pertulerat Cestius, nullius ætatis misericordia commoveret. Incendit autem non solum civitatem, sed etiam omnes circum vicos et oppidula quædam, penitus desolata, nonnulla quorum habitatores ipse cepisset. |

Vespasian descended on Gabara and, finding it devoid of any large, combat-capable number, took it at first assault. He marched into the town and killed all males past puberty, with mercy to neither young nor old, motivated by hatred of the people and by the memory of the catastrophe Cestius had suffered. He burnt down not only the town itself but all the surrounding villages as well as some hamlets, completely abandoned, and some whose inhabitants he took as captives. |

| 2 |

| Josephus autem, quam tuitionis causa optaverat civitatem ipse metu replevit. Nam Tiberienses nunquam eum, nisi de omni bellum desperasset, in fugam versum iri credebant ; neque in hoc eos voluntatis ejus fallebat opinio. Videbat enim res Judæorum quorsum evaderent, unamque illos viam salutis habere, si propositum mutavissent. Ipse vero, quamvis adhuc sibi speraret a Romanis veniam tribuendam, mori tamen sæpe maluisset quam, prodita patria, cum dedecore administrationis sibi creditæ, apud illos feliciter agere, contra quos fuerat missus. |

Josephus’ hurried arrival produced panic in the city he had chosen as a refuge. The people of Tiberias concluded that if he had not completely written off the war, he would never have taken to flight. In this they were making no mistake about his views; for he foresaw where the actions of the Jews were leading, and knew that their only path to safety was to change their decision. He himself, on the other hand, even though he still hoped the Romans would pardon him, would nonetheless rather have died over and over again than betray his fatherland and, to the disgrace of the office entrusted to him, live an enjoyable life among the very ones he had been sent against. |

| Decrevit igitur Hierosolymam primatibus quemadmodum sese res haberent cum fide perscribere, ne vel minus extollendo vires hostium, timiditatis mox argueretur, vel minus aliquid nuntiando, fortasse cœpti etiam pænitentes ad ferociam revocaret : utque si fœdus eis placeret, cito rescriberent ; aut si bellandum esset, dignum ei contra Romanos exercitum mitterent. Ille quidem hac epistola scripta, mature mittit qui Hierosolymam litteras ferret. |

So he determined to write to the leaders in Jerusalem about the reality of the situation, lest by insufficiently inflating the strength of the enemy he would be accused of cowardice or, by insufficiently reporting something, he might reignite the ferocity of those who had begun to have second thoughts : if they decided on truce negotiations, they should write back at once; or, if war were the decision, they must send him adequate forces. Having written these things in a letter, he immediately sent a man to take it to Jerusalem. |

| 3 |

— Caput C-7 —

Jotapatæ obsidio. |

| Vespasianus autem, Jotapatam exscindere cupiens (nam in eam plurimos hostium refugisse cognoverat, et præterea validissimum hoc eorum esse receptaculum), præmittit pedites cum equitibus qui montanum iter coæquarent, saxis asperum, ac peditibus quoque difficile, omnino vero equitibus invium. Et hi quidem quatriduo fecere quod jussum est, latamque aperuere exercitui viam. Quinto autem die, qui mensis Maji vigesimus et primus erat, prior Josephus in Jotapatam ex Tiberiade venit, abjectosque Judæorum spiritus erigit. |

Vespasian was eager to destroy Jotapata; for he was informed that the biggest number of the enemy had take refuge there, and that in addition it was their strongest bulwark. He therefore sent infantry and cavalry ahead to level the mountainous road, rough with stones, difficult for infantry and for cavalry quite impossible. They took only four days to complete their task, opening a broad highway for the army. On the fifth day — the 21st {(meant is probably the 11th)} of May — Josephus got to Jotapata first, coming from Tiberias, and awakened new courage in the sinking hearts of the Jews. |

| Quum vero transitum ejus Vespasiano quidam transfuga nuntiasset, utque mox civitatem peteret incitaret, veluti cum ea totam Judæam capere posset si Josephum subjugasset, hōc ille nuntio pro maxima felicitate percepto, Dei providentia factum ratus ut, qui hostium prudentissimus videretur, ultro se etiam in custodiam traderet voluntariam, statim quidem cum equitibus mille Placidum mittit, unaque decadarcham Æbutium, tam manu quam prudentia virum insignem, circumvallare civitatem jussit, ne clam inde Josephus elaberetur. |

When a deserter reported the news of his arrival to Vespasian and urged him to attack the city immediately, given that with it, provided he got Josephus, he would take all Judæa captive, Vespasian seized on this news as a great piece of luck. It must be by divine providence, he thought, that the man who was considered the most capable of his enemies had voluntarily surrendered himself to captivity. So without losing a moment, he sent 1,000 horsemen under Placidus together with the decurion Æbutius — a man renowned for energy and intelligence — with orders to ring the town and prevent the secret escape of Josephus. |

| 4 |

| Postero autem die, cuncta manu comitatus ipse consequitur, et post meridiem usque acto itinere, ad Jotapatam pervenit ; adductoque in septentrionalem ejus partem exercitu, in quodam tumulo castra ponit, distante ab oppido stadiis septem. Consulto autem quam maxime conspici ab hostibus affectabat, ut visu attoniti turbarentur. Quod etiam factum est ; eosque tantus continuo stupor invasit, ut muris egredi nullus auderet. At Romanos tota die ambulando fatigatos, civitatem statim aggredi piguit ; ob eam causam duplici acie circumdato oppido, tertium extrinsecus agmen equitum posuere, omnes Judæis exitus obstruentes. Sed ea res illos in salutis desperatione audaciores effecit. Quippe in bello nihil est necessitate pugnacius. |

Next day the general himself followed with his entire force and, marching until after midday, arrived before Jotapata. He led the army to the north of the town and pitched his camp on a rise three quarters of a mile from the town, deliberately trying to make himself as conspicuous as possible to the enemy in order to demoralize them by the sight. Indeed, this happened: the Jews were so shocked that no one dared to go outside the walls. The Romans, after marching all day, were disinclined to make their onslaught at once, but they put a double line of infantry around the town, stationing a third line outside them, formed from the cavalry, and so blocking all paths of egress to the Jews. But in their despair of safety, that action made them all the more daring; for in war nothing is more bellicose than necessity. |

| 5 |

| Itaque postridie impetu in muros facto, Judæi primo quidem locis suis manentes, Romanis castra ante muros habentibus resistebant. Postea vero quam Vespasianus et sagittarios et funditores, omnemque jaculatorum multitudinem adhibitam, missilibus in eos permisit uti, atque ipse cum peditibus in adversum collem, unde murus expugnabilis erat, niti cœpit, tunc civitati metuens Josephus et cum eo cuncta Judæorum prosiluit multitudo ; omnesque in Romanos pariter irruentes, procul a muris eos deterruere, multa manu simul et audacia patrando facinora. |

Next morning the assault began. At first the Jews merely held their ground opposite the Romans who were encamped outside the walls. So Vespasian brought up against them his archers and slingers and whole projectile force, with instructions to keep shooting at them while he himself with the infantry pushed up the slope opposite the point where the wall was assailable. Then Josephus, fearing for the city, and with him the whole body of Jews rushed out on attack. Falling in a body together on the Romans, they drove them back from the walls, simultaneously performing many deeds of prowess and daring. |

| Neque minora tamen patiebantur quam faciebant. Nam quantum ipsos salutis desperatio, tantum pudor incendebat Romanos. Et hos quidem peritia cum fortitudine, illos autem duce iracundia ferocitas armabat. Denique cum tota die pugnatum fuisset, prœlium nox diremit ; in quo Romanorum plurimis sauciatis, tredecim interfecti sunt ; Judæorum autem cum sescenti essent vulnerati, septem et decem ceciderunt. |

However, they did not suffer fewer losses than they inflicted; the Jews were inflamed by despair of salvation, the Romans just as effectively by a sense of shame; the latter were armed with experience as well as prowess, the other, enraged, by blind fury. All day long they were locked in battle till night parted them. Roman casualties were very heavy, and included thirteen killed; on the Jewish side, the dead numbered seventeen and the wounded six hundred. |

| 6 |

| Nihiloque minus, Romanis postridie iterum irruentibus occurrunt, multoque fortius restiterunt, ex eo scilicet fiduciam nacti quod eos pridie præter spem sustinuerant. Sed eos quoque pugnaciores experti sunt, quod eorum iracundiam pudor incenderat, vinci credentium, nisi cito vicissent. Itaque per dies quinque Romanis minime ab aggressione cessantibus, etiam Jotapatenorum excursus agebantur, murique fortius oppugnabantur. Et neque Judæi vires hostium formidabant, neque Romanos difficultas oppidi capiendi lassabat. |

On the next day the Romans attacked again, and the Jews, sallying out against them, met their advance with greatly increased determination, emboldened by the fact that, contrary to expectations, they had held them off on the previous day. But they found the Romans, too, more agresssive than before; for shame put them into a blazing passion, and they considered a failure to win quickly equivalent to a defeat. For five days, as the Roman attacks continued without letup, the Jotapenians also made sallies, and the walls were attacked more fiercely; the Jews were not dismayed by the strength of the enemy, nor did the difficulty of capturing the town tire the Romans. |

| 7 |

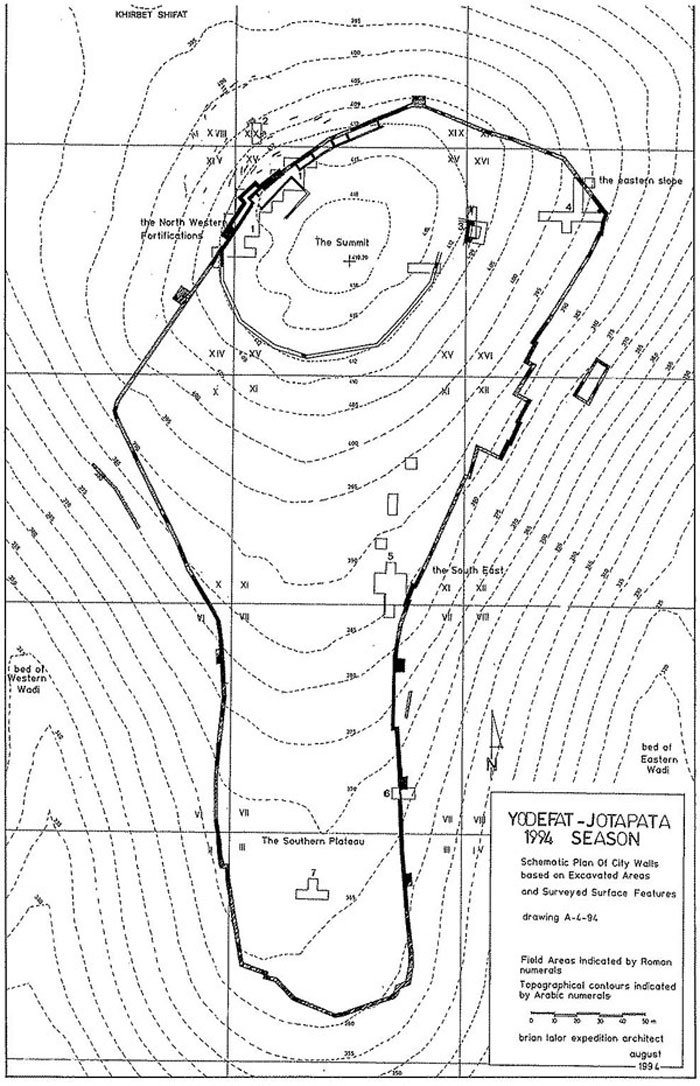

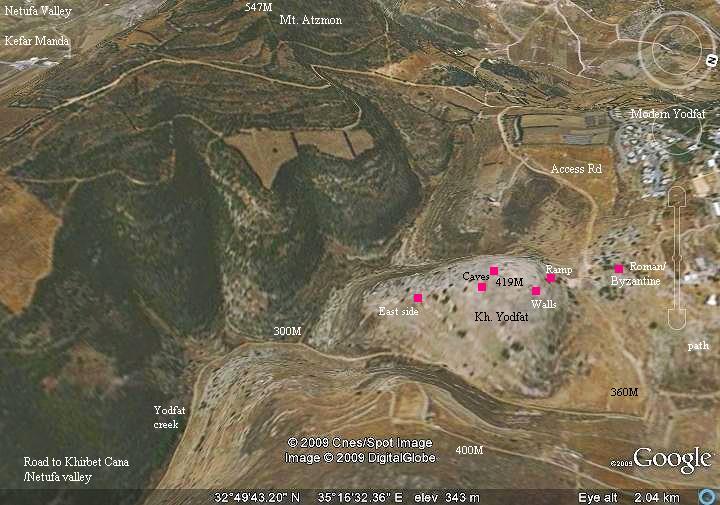

| Etenim Jotapata paulo minus tota rupes est, ex aliis quidem partibus undique vallibus immensis præceps, ut earum altitudinem oculis deprehendere cupientium aspectus ante deficiat. Ab una vero tantum boreæ parte adiri potest, ubi per transversum latus desinentis montis ædificata est, quod quidem ipsum muro civitatis Josephus fuerat amplexus, quo inaccessa essent hostibus superiora cacumina. Aliis vero circum montibus tecta, priusquam in eam perveniretur, a nullo poterat conspici ; Jotapata quidem sic erat communita. |

All of Jotapata is hardly less than a cliff, on all the other sides dropping off steeply into canyons so enormous that the vision of those wishing to grasp their depth by looking would fail before doing so. It can be accessed only from the north, where the town is built across an angled flank of the foot of a mountain. Josephus had included this very side with the city wall, so that the higher peaks would be inaccessible to the enemy. A ring of other mountains screened the town so effectively that, until a man had actually gotten inside it, it could not been seen at all. That was how Jotapata had been fortified. |

The Ruins of Jotapata from the North |

| 8 |

| Vespasianus autem et cum natura loci simul certandum putans et cum audacia Judæorum, incipere obsidionem acriter statuit ; advocatisque rectoribus sibi subditis, de aggressu deliberabat. Quumque aggerem fieri placuisset qua parte murus facilis erat accessui, totum ad comparandam materiam misit exercitum ; oppidoque propinquis montibus excisis, magnaque vi lignorum et lapidum comparata, cratibusque ad evitanda jacula desuper missa per vallos dispositis, his protecti aggerem construebant. Nulla autem noxa vel minima telorum erat quæ de muro jacerentur. |

Vespasian, recognizing that he had to fight with the terrain at the same time as with the daring resistance of the Jews, decided to prosecute the siege vigorously; he called a meeting of his senior officers to plan the assault. It was resolved to build a siege ramp where the wall was easy to get at, so Vespasian sent out the whole army to collect material. The heights around the town were stripped of their trees, and a huge amount of wood and stones was readied. Then, as a shield from the missiles thrown from above, arrays of protecting roofs were set up on posts and the siege ramp was constructed under their shelter, the bombardment from the walls causing few if any casualties. |

Jotapata City Wall Excavations (1994) |

| His autem alii, terram ex propinquis tumulis eruentes, sine intermissione suppeditabant, cunctisque trifariam distributis, nullus erat otiosus. At Judæi super eorum tegmina saxa ingentia et omne telorum genus curabant immittere, quæ licet minime penetrarent, magnos tamen crepitus dabant, et horribile impedimentum erat operantibus. |

Others, digging up earth from nearby mounds, kept up a constant supply of earth to these workers ; thus, with all of them divided into three groups, nobody was idle. Meanwhile the Jews launched huge rocks onto their screens, together with every kind of projectile; even though they did not penetrate, nevertheless they made a great deal of noise and were a frightful hindrance to the workers. |

| 9 |

| Tunc igitur Vespasianus, machinis missilium circumpositis (erant autem omnes centum sexaginta), in eos qui super murum astarent jussit tela contendi ; simulque ex catapultis lanceæ percurrebant, saxaque tormentis ingentia mittebantur, ignisque et sagittarum frequentissima multitudo quæ non solum murum, sed etiam totum intra jactum earum spatium Judæis inaccessum fecere ; Arabum enim sagittariorum manus, et jaculatores, itemque funditores et omnes machinæ tela jaciebant. |

Vespasian next set up his artillery in a ring — a hundred and sixty engines in all — and gave instructions to shoot at the men on the wall. In a synchronized barrage, lances shot from the catapults, and enormous stones were discharged from rock-launchers, together with firebrands and a dense shower of arrows, driving the Jews not only from the wall but also from the entire area within missile range; for a host of Arab archers with all the javelin-men and slingers let fly at the same time as the artillery. |

Satellite View of Jotapata Ruins

(North is to the Right) |

| Neque tamen his Judæi prohibiti ne desuper propugnarent quieti erant, sed excurrendo per cuneos more latronum, tegmina operantium detrahebant, nudatosque feriebant ; et ubi illi cessissent, aggerem dissipabant, vallorumque munimenta cum cratibus igni tradebant ; donec Vespasianus, cognito hujus damni causam ex distributione operum contigisse quod interjecta spatia Judæis locum aggrediendi præberent, adunavit tegmina ; conjunctisque pariter viribus, obreptiones hostium præpeditæ sunt. |

The Jews, however, though prevented from fighting from the higher position, were by no means idle. By darting out in platoons, guerrilla-fashion, they would tear away the screens sheltering the workers and assail them in their unprotected state; and wherever the Romans retreated, they would break up the siege ramp and set fire to the posts and protecting roofs. This continued until Vespasian realized that the spacing between the work locations was the cause of the trouble, since the gaps provided the Jews with an avenue of attack. He then interlinked all the shielding and at the same time strung the troop units together, putting to an end the Jewish surprise attacks. |

| 10 |

| Erecto autem propemodum aggere, pauloque minus æquato propugnaculis, indignum esse ratus Josephus, nihil contra moliri quod oppido saluti foret, convocat fabros, murumque altius jubet extolli. Quumque illi tam multis obstantibus jaculis minime ædificare posse affirmarent, hanc eis defensionem excogitavit. Sudibus fixis, per eos boum coria recentia extendi præcepit, quæ emissos tormentis lapides sinuata susciperent, quibusque repulsa tela cetera dilaberentur et ignis humore languesceret. Hisque ante fabros oppositis, illi murum die noctuque operando, ad viginti cubitorum altitudinem erexerunt, crebris etiam turribus in eo constructis, minisque validissimis aptatis. Quæ quidem res Romanis jam intra civitatem se esse credentibus magnum mærorem comparavit — tam Josephi molitione quam oppidanorum obstinatione perterritis. |

As the siege ramp was now rising and had almost reached the battlements, Josephus, thinking it disgraceful if he failed to invent some countermeasure to save the town, called stone-masons together and instructed them to raise the wall higher. When they declared that it was impossible to build under such a hail of missiles, he devised protection for them as follows: he ordered that poles be set in place and that, by the workmen, fresh oxhides be hung up which would by folding inward consequently catch the stones hurled by the engines; and the other missiles, also stopped, would fall down off of them, and firebrands would be quenched by their moisture. With these devices protecting the builders, they worked on the wall day and night and raised it to a height of thirty feet, built towers on it at short intervals, and fitted it out with an extremely strong parapet. At this the Romans, who had fancied themselves already inside the town, were plunged into deep despondency, overawed by the efforts of Josephus and the determination of the defenders. |

| 11 |

— Caput C-8 —

Obsidio Jotapatenorum a Vespasiano, et diligentia Josephi, deque Judæorum excursione in Romanos. |

| At Vespasianus et calliditate consilii, et hostium audacia magis irritabatur ; qui jam recepta ex munitione fiducia, Romanos ultro incursabant ; inque dies singulos prœlia catervatim, et cujusque modi latrocinales doli, et eorum quæ casus obtulisset rapinæ aliorumque incendia fiebant ; donec Vespasianus, retento milite a pugna, statuit obsidere civitatem, ut eam usui necessariorum penuria caperet. Aut enim coactos inopia sibi supplicaturos, aut si ad finem usque in eadem pertinacia duravissent, fame consumendos ejus habitatores putabat ; multoque faciliores expugnatu fore, si post intervallum rursus anxiis incubuisset. Itaque omnes exitus eorum asservari præcepit. |

Vespasian was exasperated both by the cleverness of the stratagem and by the audacity of the enemy who, encouraged by the new fortifications, made unprovoked attacks on the Romans; and day after day there were battles on the level of skirmishes. Every device of guerilla war was brought into play, there was a plundering of eveything that chance offered them, and other things beside {the siege ramp} were set on fire. At length Vespasian recalled his troops from the fight and determined to blockade the town in order to capture it through the dearth of provisions; its inhabitants would either be compelled by privation to beg for mercy or, if they stubbornly held out to the bitter end, die of starvation. He was confident that they would be much easier to defeat if after a waiting period he made a fresh onslaught on men under stress. He therefore ordered all of their points of egress to be guarded. |

| 12 |

| Illi autem frumenti quidem aliarumque omnium rerum intus habebant copiam, præter salem. Aquæ vero penuria eos affligebat, quia neque fons erat intra civitatem et, imbre contentis habitatoribus, rara est in illo tractu æstivis mensibus pluvia. Quo tempore obsessi etiam hoc vehementius afficiebantur, quod arcendæ siti fuerat excogitatum, quodque fieri, velut omnis aqua jam defecisset, ægre ferebant. |

Inside there was plenty of grain and all other necessities except salt, but they suffered from inadequacy of water, as there was no spring within the walls, with the townsfolk restricted to rainwater — and there is little or no rain in the district during the summer months. Being besieged precisely in that season, they were all the more distressed by the fact that a strategy had been devised to embargo their thirst, and were very upset, as though the water supply had already failed completely. |

| Josephus enim, quum et civitatem videret abundare aliis rebus fortesque animo viros esse, quo longiorem Romanis obsidionem faceret quam sperabant, jam tum potum mensura civibus ministrabat. Illis autem conservari aquam penuria gravius esse videbatur, amplioremque cupiditatem movebat quod jus bibendi liberum non haberent ; ac velut ad extremam sitim perventum esset, labori cedebant. Hoc autem modo affecti, Romanos latere non poterant, qui ex adverso colle trans murum in unum eos confluere locum et aquæ mensuram accipere prospectabant, quo etiam ballistarum pervenientibus telis, plurimos occidebant. |

For Josephus, seeing that the town had all other necessities in abundance and that morale of the men was high, in order to draw out the siege for the Romans longer than they were expecting, had already been rationing water to the citizens. They, however, found this husbanding of resources harder to bear than actual shortage; they were driven by an even greater craving because they did not have the right to drink freely and began to flag as if they had already reached the last degree of thirst. Their condition could not be hidden from the Romans who from the hill opposite watched them across the wall queuing up at one place and getting their ration of water; so by targeting this spot with their ballistic weaponry, they killed quite a few. |

| 13 |

| Vespasianus quidem non multo post, exhaustis puteis, ipsa sibi necessitate traditum iri civitatem sperabat. Josephus autem, ut hanc ejus spem frangeret, jussit quam plurimos per murorum minas immersa undis atque umida vestimenta suspendere, ut omnes repente aqua perfluerent. Ex quo mæror simul Romanis ac timor erat, quum tantum aquæ viderent eos ludibrio consumere, quos potu indigere credebant. Denique dux belli etiam ipse, quia penuria civitatem posse capere desperasset, iterum consilium ad vim atque arma convertit, Judæis quoque id maxime cupientibus, quod nec se nec civitatem salvam fore credebant et, priusquam fame vel siti perirent, mortem bello optabant. |

Vespasian hoped that before long the cisterns would be empty and the town would be forced to capitulate to him. But Josephus, determined to shatter this hope, ordered as many men as possible to soak their outer garments in water and hang them wet around the battlements to make them all suddenly run with water. The result was depression and anxiety in the Roman ranks, when they saw so much water thrown away in jest by men who were thought to be in need of drinking water. The commander-in-chief himself, despairing of being able to capture the town through shortage, reverted to force of arms. Nothing could have pleased the Jews more; for they had long believed that neither they nor the town could be saved, and preferred death in battle to dying of hunger and thirst. |

| 14 |

| Josephus tamen, præter hoc etiam aliud consilium quo sibi copia pararetur per quandam vallem deviam, proptereaque minus curiose habitam a custodibus, excogitavit. Mittendo enim per occiduas ejus partes litteras ad quos vellet Judæos extra civitatem degentes, ab his omnia usui necessaria et quæ in civitate defecerant, accipiebat, mandato commeantibus ut plerumque ad excubias reperent, terga velleribus tecti, quo si qui eos nocte vidissent, canum similitudine fallerentur. Idque factitatum est, donec ejus fraudem vigiles persenserunt, vallemque cinxerunt. |