| DE BELLO JUDAICO LIBER PRIMUS |

THE JEWISH WAR BOOK ONE |

|

||||||||

| De Bello Judaico Libri VII (interprete, ut vulgo creditum est, Rufino Aquilejensi) ex interpretatione Rufini, à Gelenio emendata. Genevæ : Excudebat Petrus de la Rouière, {ᑕIᑐ Iᑐᑕ XI} |

The Jewish War 7 Books interpreted by (as generally believed) Rufinus Aquilejensis and emended by Gelenius. Geneva Printed by Petrus de la Rouière, 1611. |

| Interprete Rufino Aquilejensi, ad Græcum collati et emendati per Sigismundum Gelenium |

The Latin text is mostly excerpted from a 1611 Greek-Latin edition of Flavius Josephus in which the translation from Greek into Latin was done by Rufinus of Aquileja (A.D. 340/345 – 410), emended by Sigismund Gelenius (1497 – 1554), and printed side-by-side with the original Greek (published Basel 1524, Geneva 1611). |

| A number of other translations — Latin, English, German, French and Spanish — from the original Greek have been helpful in preparing this English translation from the Latin.

The most readable basis for the Latin text here presented may be found in two books by Edvardus Cardwell, S.T.P, published in 1837: Volume 1 and Volume 2. A much older copy (published in 1611) by Sigismund Gelenius, with accompanying Greek text, is a main source for Cardwell’s work. Also quite useful, because freest from textual errors despite its age, is Flavii Josephi Hebræi Scriptoris Antiquissimi de Bello Judaico ac Expugnata per Titum Cæsarem Hierosolyma Libri Septem. Interprete Rufino Aquilejensi. Post complures Authoris editiones, novissime a reliquis ejusdem operibus separatim, ob Historiæ dignitatem, typis dati, Tyrnaviæ (Tirnau [Pressburg], Hungary): Typis Academicis Societatis Jesu, Anno MDCCLV (1755). This and others may now be found as Google scans on the internet. The Greek text here consulted as the basis for Rufinus’s Latin translation is found in Flavius Josephus: De bello Judaico. Der jüdische Krieg. Griechisch und Deutsch, Herausgegeben und mit einer Einleitung sowie mit Anmerkungen versehen von Otto Michel und Otto Bauernfeind. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1959-1962/63/69. Band (Volume) I presents Books 1-3; II,1, Books 4 & 5; II,2, Books 6 & 7; III, Ergänzungen (Supplements) und Register. The notes are also helpful, although must be used judiciously; see the critique by Carl Schneider in Theologische Literaturzeitung: Monatsschrift für das gesamte Gebiet der Theologie und Religionswissenschaft, Siebenundneunzigster Jahrgang, 1972, available as a PDF file at the Universitätsbibliothek Tübingen, pp. 341f. in the PDF, 659f. in the Monatsschrift itself. | |

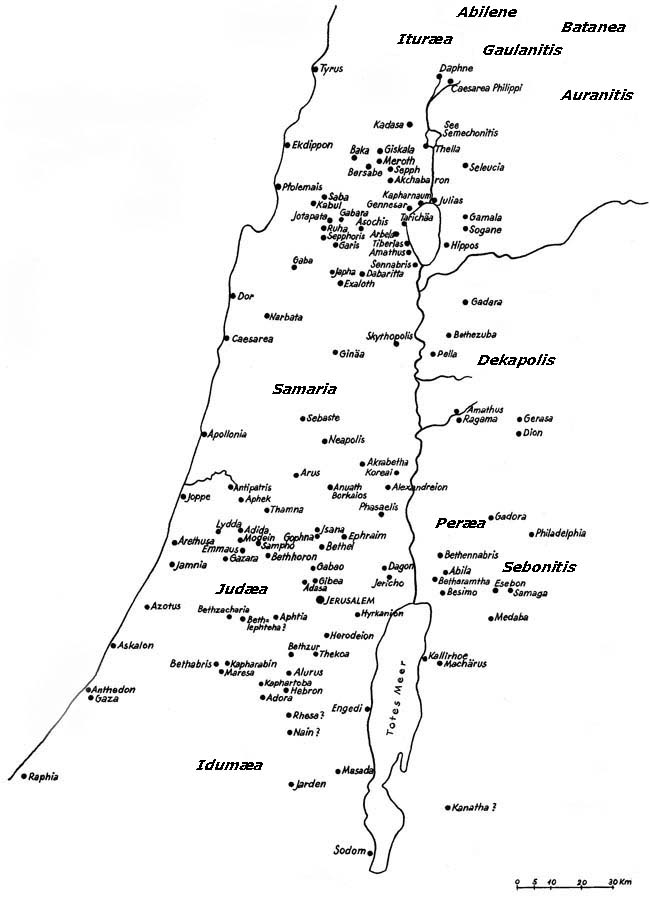

| Palæstina with locations mentioned by Josephus  |

| Prologus | Prologue |

| 1 | |

| Quoniam bellum quod cum populo Romano gessere Judæi omnium maximum quæ nostra ætas vidit, quæque auditu percepimus, civitates cum civitatibus genteve commisisse cum gentibus, quidam, non quod rebus interfuerint, sed vana et incongrua narrantium sermones auribus colligentes, oratorum more perscribunt, qui vero præsto fuerunt, aut Romanorum obsequio aut odio Judæorum contra fidem rerum falsa confirmant, scriptis autem eorum partim accusatio, partim laudatio continetur, nusquam vero exacta fides repetitur historiæ — idcirco statui quæ retro barbaris antea misi, patria lingua digesta, Græce nunc his qui Romano Imperio reguntur exponere, ego Josephus, Matathiæ filius, Hebræus genere, sacerdos ex Hierosolymis, qui et initio cum Romanis conflixi, posteaque gestis, quia necessitas exegit, interfui. | Because on the one hand, some people, not because they were present at the events, but rather, gathering by ear the blather of those expounding imaginary doings and inconsistencies, are writing at length in rhetorical style about the war which the Jews waged with the Roman people — the greatest of all the ones that our age has witnessed and that, through hearing, we have learned about, that cities have waged against cities or peoples against peoples —, while on the other hand those who were indeed present, either out of obsequiousness toward the Romans or hatred toward the Jews, assert falsehoods contrary to faithfulness to the facts, with in part accusations, in part praises being contained in their writings, but nowhere any accurate faithfulness to history being found — because of this I have decided now to publish in Greek for those who are ruled by the Roman Empire what, set forth in my ancestral language, I earlier sent to the non-Greek speakers back there — I, Josephus, son of Matthew, of Hebrew stock, a priest from Jerusalem, who originally fought against the Romans and afterward, because fate forced me, was present at the events. |

| 2 | |

| Nam quum hoc, ut dixi, bellum gravissimum exortum est, Romanorum quidem populum domesticus motus habebat. Judæorum autem, qui ætate validi et ingenio turbulenti erant, manu simul ac pecunia vigentes adeo temporibus insolenter abusi sunt ut, pro tumultus magnitudine, hos possidendarum spes, illos amittendarum partium Orientis metus invaderet. | For when this — as I said — most severe war began, internal disturbances were vexing the Roman people. But those of the Jews who were strong in age and of turbulent disposition, thriving both in forces and money, arrogantly abused the times to such an extent that, on account of the size of their insurrection, the hope of seizing parts of the Orient overcame the ones, the fear of losing them, the others. |

| Quoniam Judæi quidem cunctos etiam qui trans Euphratem essent gentiles suos secum rebellaturos esse crediderant. Romanos autem et finitimi Galli irritabant, nec Germani quiescebant : dissensionumque plena erant omnia post Neronem, et multi quidem temporum occasione Imperium affectabant ; lucri autem cupidine exercitus rerum novandarum cupidi erant. | For the Jews had believed that all of their kinsmen who were across the Euphrates would also rebel with them. Moreover the neighboring Gauls were harassing the Romans, and the Germans were not quiet either; and everything was full of turmoil after Nero {(committed suicide, A.D. 68 June 9)}, and many, given the opportunity of the times, were striving for supreme Imperial power; moreover the armies, in their desire for gain, were eager for revolution. |

| Itaque indignum esse duxi, errantem in tantis rebus dissimulari veritatem ; et Parthos quidem, ac Babylonios, Arabumque remotissimos et ultra Euphratem gentis nostræ incolas, itemque Adiabenos, mea diligentia vere cognoscere unde cœpisset bellum, quantisque cladibus constituisset, quove modo desiisset — Græcos vero et Romanorum aliqui qui militiam secuti non essent, figmentis sive adulationibus captos, ista nescire. | So I thought it inappropriate for the truth, going astray in such important matters, to be distorted, and for the Parthians and Babylonians and most distant of the Arabs and those of our people living beyond the Euphrates, as well as the Adiabenes, to know, through my careful work, where the war had started from, and with what disasters it was involved, and how it had ended —, but for the Greeks and some of the Romans who did not accompany the campaigns, being taken in by fictions or flatteries, not to know those things. |

| 3 | |

| Atqui « historias » audent eas inscribere qui, præter hoc (ut mihi quidem videtur) quod nihil sani referunt, etiam de proposito decidunt. Nam dum Romanos volunt magnos ostendere, Judæorum res extenuant et in humilitatem dejiciunt. Non autem intellego, quonam pacto magni esse videantur qui parva superaverint. | Moreover, those who have the effrontery to entitle their stuff “histories” — besides the fact that (as indeed it seems to me) they recount nothing intelligent —, even miss their objective. For while they want to show the Romans as great, they minimize and degrade to insignificance the actions of the Jews. I, however, do not understand how those who have overcome small things can appear to be great. |

| Et neque longi temporis eos pudet quo bellum tractum est, neque multitudinis Romanorum quam in ea militia labor exercuit, neque ducum magnitudinis, quorum profecto gloria minuitur si, quum multum pro Hierosolymis desudaverint, rebus per eos prospere gestis aliquid derogetur. | And they show no reverence, either for the long time during which the war was drawn out, or for the multitude of Romans that the work in that campaign entailed, or for the greatness of the generals whose glory is certainly diminished if, since they had endured a great deal before Jerusalem, something is taken away from the deeds successfully accomplished through them. |

| 4 | |

| Nec tamen ego, contentione Romanas res extollentium, gentiles meos amplificare decrevi, sed facta quidem utrorumque sine ullo mendacio prosequar ; dicta vero de factis reponam, dolori atque affectioni meæ in deflendis patriæ cladibus indulgens. Nam quod domesticis dissensionibus est eversa, et in Templum sacrosanctum invitas Romanorum manus atque ignem Judæorum tyranni traxere, testis est qui eam vastavit : ipse Cæsar Titus, per omne bellum miseratus quidem populum quod a seditiosis custodiretur, sæpe autem consulto differri passus civitatis excidium, protracto obsidionis spatio, dummodo belli pæniteret auctores. | Nevertheless, I have decided not, in competition with those extolling the Roman side, to amplify my kinsmen; rather, I will describe in detail the actions of both sides without any mendaciousness. I will instead just present statements of the events — allowing for my emotions in mourning the catastrophes of my fatherland. For witness to the fact that it was destroyed by internal conflicts, and that the dictators of the Jews dragged the Romans’ reluctant hands and fire onto the sacrosanct Temple is the one who laid it waste: Cæsar Titus himself, throughout the entire war indeed feeling sorry for the populace that was imprisoned by the rebels — often even deliberately allowing the annihilation of the City to be held up, drawing out the length of the siege only so that the perpetrators might repent of their war. |

| Quod si quis me adversus tyrannos eorumque latrocinium accusatorie loqui putet, vel patriæ miseriis ingementem calumniari præter legem historiæ, dolori veniam tribuat. Ex omnibus enim quæ Romano Imperio parent, solam nostram civitatem contigit ad summum felicitatis fastigium evadere, eandemque in extremum miseriæ dejici. | But if anyone should think that I am speaking accusatorily against the dictators and their outrages, or that, in lamenting the misfortunes of my fatherland, I am making misrepresentations contrary to the precepts of history-writing, let him make allowances for my grief. For of all those that submit to the Roman Empire, it happened that our City alone reached the summit of prosperity and was also plunged into the nadir of wretchedness. |

| Denique, omnium post condita sæcula res adversas, si cum Judæorum calamitatibus conferantur, superatum iri non ambigo. Et horum auctor nullus externus est — unde nec fieri potest, ut a questibus temperetur. Siquis autem durior misericordiæ sit judex, res quidem tribuat historiæ, lamenta vero scriptori, | Ultimately, I have no doubts that the misfortunes of all peoples since the beginning of time, were they to be compared with the calamities of the Jews, would be surpassed by them. And there is no external agent responsible for these things — hence it is impossible for my laments to be limited. But if anyone would be a harsher critic of pathos, let him attribute the facts to this history, but the laments to its author. |

| 5 | |

| Quanquam merito Græcorum disertos increpaverim qui, tantis rebus sua memoria gestis quarum comparatione præterita olim bella exigua redduntur, judices resĭdent, aliorum facundiæ detrahentes, quorum, et si doctrinam superant, proposito vincuntur. | And yet I may justly criticize the scholars of the Greeks who, with such great events having taken place within their own memory — events in comparison with which past wars of yore are rendered insignificant —, sit as judges, criticizing the eloquence of others by whose substantive approach, even if they surpass them in education, they are vanquished. |

| Ipsi vero Assyriorum et Medorum gesta perscribunt, veluti minus recte a scriptoribus antiquis fuerint exposita, quum in scribendo tantum eorum viribus cedant quantum sententiæ. Erat enim unicuique studium quæ vidisset facta conscribere, quoniam et interfuisset rebus gestis ; et efficaciter quod promittebat impleret — mentirique apud scientes inhonestum esse videretur. | Indeed, they themselves write down the deeds of the Assyrians and the Medes as though they had been less correctly recorded by writers of old, when in writing they are as much inferior to their talents as to their ideas. Because for each of them his concentration had been on writing down the deeds which he had seen, because he had also been present at the actual events, and he fulfilled effectively what he promised — and to lie before knowledgeable readers seemed disgraceful. |

| Enimvero nova quidem neque ante cognita memoriæ tradere, suique temporis res commendare posteris, laude ac testimonio dignum est. Industrius autem habetur, non qui alienam dispositionem atque ordinem transfert, sed qui nova dicendo etiam corpus proprium conficit historiæ. | For indeed, to hand on down to memory new facts and those not previously known, and to commend to posterity the events of one’s own time, is worthy of praise and recognition. Moreover, the man of enterprise is not considered one who rearranges the disposition and order of someone else, but who by saying something new also creates his own body of history. |

| Sed ego quidem sumptu ac labore maximo, qui quum sim alienigena, Græcis simul et Romanis gestarum rerum memoriam repono. Ipsis autem indigenis, ad quæstum quidem ac lites, ora patent linguæque solutæ sunt ; ad historiam vero, in qua verum dicendum est, summaque ope negotia colligenda sunt, obmutescunt, concessa infirmioribus neque scientibus licentia scribendi res a principibus gestas. Honoratur itaque apud nos historiæ veritas, quæ a Græcis neglegitur. | On the other hand, indeed at great expense and effort, I, who am, granted, a foreigner, lay before Greeks as well as Romans a record of military accomplishments. Moreover, as regards the native speakers themselves, their mouths are wide open and their tongues are loosed for financial gain and lawsuits; but for history, in which truth must be spoken and facts must be gathered through the utmost exertions, they are mute, yielding to weaker, and not to knowledgeable, men the permission of writing down the things achieved by their leaders. And so history’s truth, which is neglected by the Greeks, is honored among us. |

| 6 | |

| Ab origine quidem Judæos repetere, qui fuerint, quove pacto ab Ægyptiis discesserint, quasque regiones errando peragraverint et quas vel quoties incoluerint et quemadmodum inde migraverint, neque hujus esse temporis, et præterea supervacaneum, existimavi, quoniam multi ante me Judæorum de majoribus hujus gentis verissima composuerunt, et nonnulli Græcorum, quæ illi scripserant patria voce prosecuti, non multum a veritate deviarunt ; ex eo autem historiæ principium sumam, quo scriptores eorum et prophetæ nostri desierunt. | I considered this not the time, and besides superfluous, to go over the Jews from the beginning, who they were, how they left the Egyptians and in wandering, what regions they traversed, and what ones or how many times they inhabited them, and how they emigrated thence, because many of the Jews before me have written most true accounts about the ancestors of this people, and some Greeks, having followed up what they had written in their native tongue, have not deviated much from the truth; rather, I will take up the beginning of their story from the point where the Greek writers and our prophets have left off. |

| Et bellum quidem meis temporibus gestum, latius quaque potuero diligentia referam. Quæ vero ætate mea sunt antiquiora, summatim breviterque percurram: | And I will recount extensively the war waged in my time and with as much diligence as I can. I will, however, briefly run over summarily and briefly the things that are previous to my age: |

| 7 | |

| quomodo Antiochus, cognomento Epiphanes, devicta penitus Hierosolyma, quum triennium sexque menses eam tenuisset, ab Asamonæi filiis expulsus est. Deinde quod eorum posteri de regno dissentientes, ad res suas occupandas populum Romanum Pompejumque traxerunt ; quomodoque Herodes Antipatri filius eorum potentiæ finem fecerit, auxilio Sosii. | how Antiochus, surnamed Epiphanes, having held a thorougly conquered Jerusalem for three years and six months, was driven out by the sons of Hasmonæus. Then that their descendants, fighting over power, drew the Roman people and Pompey in to taking over their own possessions; and how Herod, son of Antipater, put an end to their dynasty with the aid of Sosius. |

| Tum quomodo, Herode mortuo, plebis in eos orta seditio est, Augusto quidem imperante Romanis, Quintilio autem Varo provinciam obtinente. Quodque bellum anno duodecimo imperii Neronis eruperit ; quamque multa per Cestium acciderint ; quantaque ad primos impetus armis Judæi pervaserint ; | Then how, with Herod dead, an insurrection of the people arose against them while Augustus was ruling the Romans, when Quintlius Varus was in command of the province; and how many things took place under Cestius; and what significant things the Jews achieved through arms in the first engagements. |

| 8 | |

| quoque modo accolas permunierint ; et quod Nero, propter acceptas Cestii ductu clades, summæ rei metuens, Vespasianum bello præposuerit ; et quod is cum maximo filiorum Judæam intraverit, quantumque Romanorum exercitum ducens ; quantaque manus auxiliorum per omnem cæsa fuerit Galilæam ; et quod ejus civitatum quasdam vi ceperit, alias deditione. | And how they thoroughly fortified the inhabitants; and that Nero, because of the defeats suffered under the leadership of Cestius, fearing a critical situation, appointed Vespasian as head of the war; and that he, with the oldest of his sons {(i.e., Titus)}, entered Judæa, and how great a Roman army he was leading; and how many units of auxiliaries were felled throughout the whole of Galilee; and that he took some of its cities by storm, others by surrender. |

| Ubi etiam Romanorum in bello disciplinam curamque rerum, et utriusque Galilææ spatia ; et naturam finesque Judææ, necnon et peculiarem terræ qualitatem, lacusque et fontes ; captarumque civitatum mala, cum fide sicut vidi aut pertuli, expediam. Nec etiam miserias meas celaverim, quum scientibus eas relaturus sim. | At which point I will also report, faithfully, as I saw or underwent it, on the discipline of the Romans in warfare, and their organizational management, and the regions of both Galilees {(i.e., Upper and Lower)}, and the nature and boundaries of Judæa, as well as the special character of the land, and the lakes and springs; and the sufferings of the captured cities. Nor will I conceal my own misfortunes either, since I am about to relate them to those who are aware of them. |

| 9 | |

| Deinde, quod jam fessis rebus Judæorum, Nero quidem mortem obierit, Vespasianus autem in Hierosolymam properans, imperii causa retractus sit ; quæque signa de hoc ei contigerint, Romæque mutationes ; et quod, invitus, a militibus Imperator declaratus sit ; et quod eo disponendæ Reipublicæ gratia in Ægyptum digresso, Judæorum status seditionibus agitatus sit ; quoque modo tyrannis succubuerint eorumque inter se discordias moverint. | Next, the fact that, with the Jews’ fortunes having lost momentum, Nero died, while Vespasian, hurrying to Jeruslem, was withdrawn for the sake of imperial command; and what foretokens about it happened to him, and the changes at Rome; and that, against his will, he was declared emperor by his soldiers; and that, having departed to Egypt in order to put the Republic in order, the state of the Jews was churned up with insurrection; and how they succumbed to dictators and stirred up their feuds among them. |

| 10 | |

| Et quod ex Ægypto Titus reversus bis Judæorum fines ingressus sit ; quoque modo exercitum et quo in loco congregaverit ; vel qualiter et quoties Civitatem affecerit ipso præsente seditio. | And that Titus, returning from Egypt, twice made inroads into the territory of the Jews; and how he assembled the army and in what place; or how and how many times the insurrection affected the City when he himself got there. |

| Aggressūs quoque numerosos, et quantos erexerit aggeres ; triumque murorum ambitum et magnitudinem, sive mensuram, et munitionem Civitatis ; et Fani Templique dispositionem ; ad hæc aræ spatium, mensuramque verissime dicam ; festorum quoque dierum mores aliquos, septemque lustrationes, et munia sacerdotum. | Also the numerous assaults, and what large siege ramps he constructed; and I will most accurately give the circumference and size of the walls, or their measurements, and the fortifications of the City; and the plan of the Temple and the Sanctuary; in addition, the space of the altar and its measurements; also some customs of the feastdays, and seven purifications, and the functions of the priests. |

| Itemque pontificis vestes, sanctaque Templi, cujusmodi fuerint, sine aliqua dissimulatione vel adjectione memorabo. | Likewise I will describe the vestments of the pontiff and the Holy Place of the Temple, as it was, without any concealment or addition. |

| 11 | |

| Narrabo deinde tyrannorum in suos gentiles crudelitatem, Romanorumque in alienigenas humanitatem ; quotiesque Titus, Civitatem simul ac Templum servare cupiens, ad concordiæ fœdera dissidentes provocavit. Disseram vero populi vulnera et calamitates : quamque multa mala nunc bello, nunc seditionibus, nunc fame perpessi, postea capti sint. | I shall then recount the cruelty of the overlords towards their own countrymen, and the humanness of the Romans toward aliens; and how often Titus, desiring to spare simultaneously the City and the Temple, appealed to the dissidents for a treaty of concord. I will moreover treat of the wounds of the people and their disasters, and how many evils — now by war, now by insurrection, now through starvation — they suffered, after which they were taken captive. |

| Nec vero aut perfugarum clades aut captivorum supplicia prætermittam ; vel quemadmodum Templum, invito Cæsare, conflagraverit, quamque multæ opes sacræ flamma raptæ sint, ac totius, quæ reliqua erat, Civitatis excidium ; et quæ præcesserant portenta atque prodigia, vel tyrannorum captivitatem, vel qui servitio abducti sunt, multitudinem ; aut cui quisque fortunæ sit distributus ; et quod Romani quidem belli reliquias persecuti sunt, devictorumque munimina funditus eruerunt ; Titus vero, peragrata regione, cuncta restituit. Ejusdemque reditum in Italiam, ac triumphum. | Nor will I bypass the calamities of the deserters or the executions of the captives; or how, contrary to Cæsar’s will, the Temple burned down, and how many sacred valuables were snatched from the flames, and the obliteration of the whole remaining City; and the portents and prodigies that preceded it, or the capture of the overlords or the great number who were led off into slavery; and to what destiny each one was apportioned; and that, further, the Romans followed through with the remains of the war and utterly demolished the fortifications of the vanquished; that Titus, on the other hand, traveling all through the area, restored everything. And his return to Italy and triumphal parade. |

| 12 | |

| Hæc omnia septem libris comprehensa — annixus ne vituperationem a rerum scientibus et qui bello interfuerunt sustineam — studiosis veritatis magis quam voluptatis perscripsi. Narrandi autem initium faciam hoc ordine quo capitula sunt digesta. | I have written all this contained in seven books, more for those interested in truth than in entertainiment, striving so that I should not be subject to censure from those who know the facts and who were present in the war. Moreover I will start the narrative in the sequence in which the table of contents is ordered. |

| Book 1 | |

| Containing the interval of one hundred and sixty-seven years. From the taking of Jerusalem by Antiochus Epiphanes to the death of Herod the Great. |

| ⇑ § I | |

| Qualiter Hierosolyma ab Antiocho Illustri capta erant, Templumque spoliatum : deque Matthiæ et Judæ Maccabæorum rebus gestis, et Judæ morte. | How the City Jerusalem Was Taken, and the Temple Pillaged [by Antiochus Epiphanes]. As also Concerning the Actions of the Maccabees, Matthias and Judas; And Concerning the Death of Judas. |

| 1 | |

| — Caput A-1 — De vastatione Hierosolymæ ab Antiocho. | |

| Quum potentes Judæorum inter se dissiderent eo tempore quo de tota Syria cum Ptolemæo Sexto Antiochus, qui Epiphanes dictus est, ambigebat (erat autem illis contentio de potentia, quod honoratus quisque graviter ferret similibus subjugari), Onias quidam e pontificibus, postquam prævaluit, Tobiæ filios expulit Civitate. Illi autem supplices ad Antiochum confugerunt, petentes ut, ipsis ducibus, in Judæam irrumperet. Idque regi persuasum est, jampridem sic animato. Quare cum magnis militum copiis egressus et Civitatem fortiter expugnatam capit et maximam eorum multitudinem, quibus Ptolemæus carior erat, interfecit. Dataque passim militibus prædandi licentia, ipse et Templum spoliavit et quotidianæ religionis assiduitatem per annos tres sexque menses inhibuit. Pontifex autem Onias effugit ad Ptolemæum, acceptoque ab eo in Heliopolitana præfectura solo, ibi oppidum condidit Hierosolymis simile, templumque ædificavit, de quibus iterum opportune referemus. | At the time when Antiochus Epiphanes was disputing the control of Palestine with Ptolemy VI, dissension broke out among the leading Jews, who competed for supremacy because no prominent person could bear to be subject to his equals. Onias, one of the chief priests, forced his way to the top and expelled the sons of Tobias from the City. They fled to Antiochus and implored him to use them as guides and invade Judæa. This was just what the king wanted; so setting out in person with a very large force he stormed the City, killed a large number of Ptolemy’s adherents, gave his men permission to loot as they liked, took the lead in plundering the Sanctuary, and stopped the continuous succession of daily sacrifices for three and a half years. The pontiff Onias fled to Ptolemy, from whom he obtained a site in the district of Heliopolis. There he built a little town on the lines of Jerusalem and a Sanctuary like the one he had left. All this will be referred to again in due course. |

| 2 | |

| Verumtamen Antiocho neque præter spem devicta Civitas, neque populatio, neque tantæ cædes satis fuere, sed intemperantia vitiorum eorumque memoria quæ in obsidione pertulerat, Judæos cogere cœpit ut, abrogato more patrio, nec infantes suos circumciderent porcosque super aram immolarent. Quibus omnes quidem adversabantur, optimus vero quisque propterea trucidabatur. Et Bacchides, præsidiis ab Antiocho præpositus, ad naturalem crudelitatem suam præceptis impiis obsecundans, omnimodam iniquitatem excessit, quum et singulatim viros honorabiles verberaret, et communiter quotidie speciem captæ urbis exhiberet, donec eos atrocitate incommodorum, qui ea patiebantur ad vindictæ audaciam irritavit. | Antiochus was far from satisfied with his unexpected capture of the City, the loot, and the long death-roll. Unable to control his passions and remembering what the siege had cost him, he tried to force the Jews to break their ancient Law by leaving their babies uncircumcised and sacrificing swine on the altar. Meeting with a blank refusal he executed the leading recusants; and Bacchides, who was sent by him to command the garrison, finding in these monstrous instructions scope for his savage instincts, plunged recklessly into every form of iniquity, torturing the most worthy citizens one by one, and publicly displaying day after day the appearance of a captured city, till by the enormity of his crimes he drove his victims to attempt reprisals. |

| 3 | |

| Denique Matthatias, Asamonæi filius, unus ex sacerdotibus, ex vico cui nomen Modin est, cum manu domestica (nam quinque filios habebat) sicis armatus Bacchidem occidit ; et statim quidem præsidiorum multitudinem veritus, in montes refugit. Multis vero ex populo sibis sociatis, recepta fiducia descendit, commissoque prœlio, superatos duces Antiochi ex Judææ finibus exegit. Secundis autem rebus potentiam nactus, suisque volentibus — quod ab alienigenis eos liberasset — imperans, moritur, relicto Judæ principatu, qui filiorum suorum natu maximus erat. | Matthias, son of Asamonæus, a priest from the village of Modein, raised a tiny force consisting of his five sons and himself, and killed Bacchides with cleavers. Fearing the strength of the garrison he fled to the hills for the time being, but when many of the common people joined him he regained confidence, came down again, gave battle, defeated Antiochus’ generals and chased them out of Judæa. By that success be achieved supremacy, and in gratitude for his expulsion of the foreigners his countrymen gladly accepted his rule, which on his decease he left to Judas, the eldest of his sons. |

| 4 | |

| Ille autem (nec enim cessaturum existimabat Antiochum) et indigenarum conflavit exercitum, et cum Romanis primus amicitiam pepigit, Antiochumque Epiphanem iterum in fines suos ingredientem vehementissima percussum plāga repressit. Adhuc autem fervente victoria, in præsidia Civitatis impetum fecit (necdum enim cæsa fuerant), habitoque conflictu, milites de superiori Civitate, quæ pars sacra dicitur, ad inferiorem compellit. Fano autem potitus, et locum purgavit omnem, muroque cinxit et vasa nova divinis rebus curandis fabricata in templum intulit — veluti prioribus profanatis — aramque aliam ædificavit, et religionibus dedit initium. Sacri autem ritu vix Civitati reddito, moritur Antiochus. Regni autem ejus, et in Judæos odii, filius Antiochus heres exsistit. | As Judas did not expect Antiochus to take this lying down, he not only marshalled the available Jewish forces but took the bold step of allying himself with Rome. When Epiphanes again invaded the country he counter-attacked vigorously and drove him back; then striking while the iron was hot, he hurled himself against the garrison of the City, which had not yet been dislodged, threw the troops out of the Upper City, which is called the holy part, and shut them into the Lower. Then taking possession of the Temple he cleansed the whole area and walled it round, ordered a new set of ceremonial vessels to be fashioned and brought into the Sanctuary as the old ones were defiled, built another altar, and resumed the sacrifices. No sooner was Jerusalem once more the Holy City than Antiochus died, leaving as heir – both to his throne and to his hatred of the Jews – his son Antiochus. |

| 5 | |

| Quare, coactis peditum milibus L•, equitum autem prope V• milibus, LXXX• vero elephantis, montana Judææ per partes aggreditur, et Bethsuram quidem oppidum capit in loco vero cui Bethzachariæ nomen est, qua transitus erat angustior, Judas cum suis copiis occurrit. Et priusquam congrederentur agmina, Eleazarus frater ejus, prospecto præter alios excelso elephante, turrique maxima et munimentis aurei ornato, illic Antiochum esse ratus a suis procul excurrit, ruptaque hostili acie ad elephantum usque pervenit. Sed illum quidem quem regem esse opinabatur contingere, quod multum superemineret, minime potuit, beluam vero in alvo percussam super se dejecit, et obtritus interiit, nulla alia re gesta nisi quod magnum opus aggressus, vitam gloriæ posthabuit. Qui tamen regebat elephatum privatus erat. Et si casu in eo fuisset Antiochus, nihil plus Eleazaro præstitisset audacia quam ut sola spe præclari facinoris mortem videretur optasse. Hoc autem fratri ejus totius prœlii præsagium fuit. Nam fortiter quidem Judæi diuque decertarunt, sed a regiis secunda fortuna usis, numeroque præstantibus superati sunt, multisque interfectis Judas cum ceteris in Gophniticam toparchiam refugit. Antiochus autem ad Hierosolymam profectus, ibique dies paucos commoratus, penuria utensilium abstitit, relicto quidem ibi præsidio, quantum satis esse arbitrabatur, cetera vero multitudine ad hiemandum deducta in Syriam. | The new king got together 50,000 foot, about 500 horse, and 80 elephants, and marched through Judæa into the hill country. Beth-saron, a small town, fell into his hands, but at a place called Beth-zachariah, where the road narrows, he was met by Judas and his army. Before the main bodies engaged, Eleazar, Judas’ brother, noticed the tallest of the elephants fitted with a large howdah and gilded battlements, and assuming that Antiochus was on its back, ran out a long way ahead of his own lines, and hacking a way through the enemy’s close array got near to the elephant. To reach the supposed king was impossible because of his height from the ground, so he struck the beast’s under-belly, bringing it down on himself so that he was crushed to death. He had done no more than make a heroic attempt, putting glory before life itself. The rider of the elephant was in fact a commoner; even if he had happened to be Antiochus, Eleazar would have achieved nothing by his daring but the reputation of having gone to certain death in the mere hope of a brilliant success. To his brother the tragedy was a presage of the final issue. Determined and prolonged as was the Jews’ resistance, superior numbers and fortune’s favour gave the king’s soldiers the victory; with most of his own men dead, Judas fled with the remnant to the prefecture of Gophna. Antiochus went on to Jerusalem, where he remained only a few days, till lack of supplies compelled him to withdraw, leaving a garrison that he thought adequate, and taking the rest of his forces to winter quarters in Syria. |

| 6 | |

| Discessu autem regis, Judas non quiescebat, sed accessione multorum suæ gentis animatus, aggregatis etiam quos ex prœlio receperat, apud vicum Adasa cum Antiochi ducibus congreditur, factisque fortibus in prœlio cognitus, multis hostibus interfectis occubuit. Et in diebus paucis frater ejus Johannes occiditur, insidiis eorum captus qui cum Antiocho sentiebant. | After the king’s retreat Judas did not let the grass grow under his feet. Energized by the large numbers of Jews flocking to his standard and having also rallied the survivors of the battle, he challenged Antiochus’ generals near the village of Acedasa. In the battle that followed he fought magnificently and inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy, but lost his own life. Only a few days later his brother John fell victim to a plot of the pro-Syrian party. |

| ⇑ § II | |

| De Judæ successoribus, Jonatha, Simone, et Joanne Hyrcano. | Concerning the successors of Judas, who were Jonathan and Simon, and John Hyrcanus. |

| — Caput A-2 — De successionibus principum a Jonatha usque ad Aristobulum. | |

| 1 | |

| Quum autem successisset ei frater Jonathas, et in aliis quæ ad indigenas pertinerent, cautius se ageret suamque potentiam Romanorum amicitia corroboraret, Antiochi quidem filio reconciliatur. Non tamen horum ei quicquam profuit ad depellendum periculum. Namque Tryphon tyrannus, Antiochi quidem filii tutor sed insidiis eum captans et præter hoc amicis nudare cupiens, Jonathan, quum ad Antiochum paucis comitatus Ptolemaida venisset, dolo comprehendit. Eoque vincto contra Judæam movit exercitum. Unde repulsus a Simone, Jonathæ fratre, quodque ab eo superatus esset, iratus eundem Jonathan interfecit. | Judas was succeeded by another brother, Jonathan, who did everything possible to strengthen his authority in his own country, securing his position by his friendship with Rome and by making a truce with Antiochus’ son. Unfortunately none of these precautions could guarantee him security. Trypho, guardian of the young Antiochus and virtually regent, had long been plotting against the boy and endeavouring to eliminate his friends; and when Jonathan came with a very small escort to Ptolemais to see Antiochus, he treacherously seized and imprisoned him, and launched a campaign against the Jews. Then repulsed by Simon, Jonathan’s brother, he avenged his defeat by murdering Jonathan. |

| 2 | |

| Simon autem, fortiter regendis rebus intentus, Zara quidem et Joppen et Jamniam capit. Evertit autem et Accaron, subactis præsidiis, adversusque Tryphonem Antiocho auxilium præbuit, qui Doram ante expeditionem quam in Medos fecit obsidebat. Sed regis aviditatem satiare non potuit, quamvis neci Tryphonis suam quoque operam adhibuisset. Non multo enim post, Antiochus Cendebeum ex ducibus suis ad vastandam Judæam opprimendumque servitio Simonem cum exercitu misit. Ille autem, quamquam senior erat, bellum tamen juveniliter administrabat, et filios quidem suos cum validissimis præmisit, parte vero multitudinis comitatus alio latere aggreditur, multisque per multa loca insidiis etiam in montana dispositis, in omnibus superat. Clarissimaque potitus victoria, pontifex declaratur, et ducentos septuaginta post annos Judæos liberat a dominatione Macedonum. | Simon’s conduct of affairs was most efficient. He reduced Gazara, Joppa, and Jamnia in the neighborhood of Jerusalem, and demolished the Citadel after overwhelming the garrison. Later he allied himself with Antiochus against Trypho, whom Antiochus was besieging in Dora before marching against the Parthians. But he did not cause the king to modify his ambitions by helping him to destroy Trypho: it was not long before Antiochus sent an army under his general Cendebæus to ravage Judæa and reduce Simon to subjection. Simon in spite of his years showed a young man’s vigor in his conduct of the campaign; he sent his sons ahead with his strongest men, while he himself at the head of a section of his army took the offensive in another direction. He also placed large numbers of men in ambush all over the hill country and was successful in every onset; so brilliant was his victory that he was appointed pontiff, and after 170 {(Latin text: 270)} years of Macedonian control gave the Jews their freedom. |

| 3 | |

| Sed et ipse periit in convivio, captus insidiis Ptolemæi, generi sui qui, ejus conjuge duobusque filiis in custodiam conclusis, certos misit ut Johannem tertium, cui etiam Hyrcanus nomen fuit, interficerent. Cognito autem impetu qui parabatur, adolescens ad Civitatem properabat, multo populo fretus, et propter memoriam paternæ virtutis et quod iniquitas Ptolemæi cunctis esset invisa. Voluit autem Ptolemæus etam alia porta ingredi civitatem, sed a populo rejectus est, qui maturius Hyrcanum susceperat. Et is quidem statim recessit in quoddam ultra Hierichunta castellum, quod Dagon vocatur. Hyrcanus autem, paternum honorem pontificis assecutus, postquam Deo sacrificia reddidit, velociter Ptolemæum petit, et matri simul et fratribus adjumento futurus, | He too was the victim of a plot: he was assassinated at a banquet by Ptolemy, his son-in-law, who after locking up Simon’s wife and two of his sons sent a party to murder the third son, John Hyrcanus. Warned of their approach the youngster made a dash for the City, having great confidence in the people, who remembered what his father had achieved and were disgusted with Ptolemy’s iniquitous conduct. Ptolemy hurled himself against another gate but was thrown back by the citizens, who had already welcomed Hyrcanus with open arms. Ptolemy at once retired to one of the forts above Jericho, called Dagon; Hyrcanus, invested with the pontificate like his father before him, offered sacrifice to God and then hurried after Ptolemy to rescue his mother and brothers. |

| 4 | |

| castellumque aggressus, aliis quidem rebus superior erat, justo autem dolori cedebat. Ptolemæus enim, quoties premeretur, matrem ejus fratresque in murum productos, palam ut possent conspici, verberabat, eosdemque præcipitandos, nisi quam primum recederet, minabatur. Unde Hyrcanum quidem plus timor ac misericordia quam iracundia commovebat. Mater vero ejus, nihil plāgis aut intentata nece perterrita, manus protendens, filium precabatur ne vel suis fractus injuriis, parceret impio, siquidem ipsa sibi mortem a Ptolemæo propositam immortalitate duceret meliorem, dummodo ille pœnas eorum quæ in domum suam contra fas admisisset expenderet. Johannes autem nunc obstinationem matris cogitans, ac preces ejus audiens, ad irruendum impellebatur, modo verberari eam lacerarique conspiciens, effeminabatur, totusque plenus doloris erat. Ob hæc autem diu tracta obsidione, feriatus annus advenit, quem septimo quoque circuitu redeuntem, apud Judæos cessare moris est, exemplo septimorum dierum. Et in hoc Ptolemæus obsidionis requiem nactus, fratribus Johannis una cum matre occisis, ad Zenonem confugit, qui Cotylas cognominatus est, Philadelphiæ tyrannum. | His attack on the fort started promisingly enough, but was held up by his natural feelings. Every time Ptolemy was in a diffculty, he brought out John’s mother and brothers on to the ramparts where they could be seen by all, and began to torture them, threatening to throw them headlong unless John broke off the siege forthwith. This atrocity filled Hyrcanus with anger, and still more with pity and fear; but neither torture nor the threat of death could make his mother flinch – she stretched out her arms and implored her son on no account to let her cruel sufferings induce him to spare the vile creature; better death at Ptolemy’s hands than life without end, so long as he paid for his wrongs to their house. Whenever John, thrilled by his mother’s fortitude, listened to her entreaties, he launched a fresh attack; but when he saw her flesh torn with the lash, his resolution weakened and his feelings overcame him. This dragged out the siege till the Year of Rest came round, for like the seventh day, the seventh year is observed by the Jews as a time of rest. This freed Ptolemy from the siege, and after putting John’s mother and brothers to death he fled to Zeno Cotylas, the autocrat of Philadelphia. |

| 5 | |

| Antiochus autem, ob ea quæ per Simonem passus fuerat iratus, in Judæam ducit exercitum, ibique assidens Hierosolymis, Hyrcanum obsidebat. Ille autem, patefacto sepulchro David qui regum ditissimus fuerat, ablatisque inde pecuniæ plus quam tribus milibus talentorum, et Antiocho persuasit, datis ei trecentis talentis, ab obsidione discedere, primusque Judæorum privatis opibus alere peregrina cœpit auxilia. | Antiochus, eager to avenge his defeat at Simon’s hands, marched into Judæa and pitching his camp before Jerusalem besieged Hyrcanus. Hyrcanus opened the tomb of David, the wealthiest of kings, and removed more than 3,000 talents. With a tenth of this sum he bribed Antiochus to raise the siege. With the balance he did what no Jew had ever done before; he began to maintain a body of foreign mercennaries. |

| 6 | |

| Rursusque tamen, quando Antiochus, contra Medos bello suscepto, tempus ei vindictæ præbuit, confestim adversus civitates Syriæ perrexit, vacuas propugnatoribus esse ratus — quod et verum fuit. Medabam quidem et Samæam cum proximis, necnon et Šichimam, et Garizim ipse cepit, et super his Chuthæorum gentem, adjacentia Fano loca incolentium ad exemplum ejus quod est Hierosolymis ædificato. Cepit autem et Idumææ non paucas alias civitates, et præterea Doreon et Marisa. | When later Antiochus marched against the Parthians, giving him a chance to retaliate, Hyrcanus at once launched a campaign against the towns of Northern Palestine, correctly assuming that he would find no first-class troops in them. Medabe and Gamæa with the towns nearby submitted, as did Shechem and Gerizim. He was successful also against the Cuthæans, the people living round the copy of the Temple at Jerusalem. In Idumæa a number of towns submitted, including Adoreos and Marisa. |

| 7 | |

| In Samariam vero usque progressus ubi nunc est Sebaste, civitas ab Herode rege condita, ex omni eam parte concludit, filiosque suos Aristobulum et Antigonum obsidioni præfecit. Quibus nihil remittentibus, ad hoc famis penuria qui erant intra civitatem venerunt, ut etiam insuetam carnem cogerentur attingere. Igitur Antiochum adjutorem sibi advocant, Aspendium cognominatum. Qui, quum prompta eis voluntate patuisset, ab Aristobulo et Antigono superatur. Et ille quidem ad Scythopolim usque persequentibus eum, memoratis fratribus effugit. Hi vero, in Samariam reversi, et multitudinem iterum intra murum concludunt, et expugnata civitate ipsam diruunt, et habitatores ejus captos abducunt. Prospere autem gestis ita cedentibus, alacritatem refrigescere non sinebant, sed cum exercitu Scythopolim usque progressi, et ipsam pervaserunt, et agros intra Carmelum omnes inter se partiti sunt. | Advancing to Samaria, where now stands Sebaste, the city built by King Herod, he constructed a wall completely around it and entrusted the siege to his sons Aristobulus and Antigonus. They pressed it relentlessly, bringing the inhabitants so near to starvation that they resorted to the most unwonted food. They appealed for aid to Antiochus the Aspendian. He readily agreed, but was defeated by Aristobulus and his men. Chased by the brothers all the way to Scythopolis he managed to escape; they, returning to Samaria, again shut the people inside the walls, then took the city, demolished it, and enslaved the inhabitants. As success followed success they lost none of their ardor, but marching their forces as far as Scythopolis overran that region and ravaged all the country inland from Mount Carmel. |

| 8 | |

| — Caput A-3 — De Aristobulo, Antigono, Juda Essæo, Alexandro, Theodoro et Demetrio. | |

| Secundarum autem rerum Johannis et filiorum ejus invidia seditionem gentilium concitavit, multique adversus eos collecti non quiescebant, donec aperto bello devicti sunt. Reliquum vero tempus Johannes quum fortunatissime viveret, et optime rebus per annos XXX• et tres administratis, et quinque filiis relictis, moritur, vir plane beatissimus et qui nullam dedisset occasionem cur ejus causa de fortuna quispiam quereretur. Denique tria vel maxime præcipua solus habebat : nam et gentis princeps et pontifex erat, et præterea propheta cum quo Deus ita colloquebatur ut futurorum nihil penitus ignoraret. Quinetiam de duobus majoribus filiis suis, quod rerum domini permansuri non essent, prævidit atque prædixit. Quorum vitæ quis fuerit exitus, narrare non indignum videtur, quantumque a paterna felicitate deverterint. | Jealousy of the continued success of John and his sons aroused the bitter hostility of their fellow countrymen, who gathered in large numbers and engaged in active opposition, which at last flared up in open war and ended in defeat. For the rest of his natural life John enjoyed prosperity, and after no less than thirty-one {(Latin: 33)} years of admirable administration he died leaving five sons, blessed if ever a man was and with no cause to blame fortune as far as he was concerned. He alone enjoyed the three greatest privileges at once — political power, the pontificate, and the prophetic gift. So constant was his divine inspiration that no future event was hidden from him; for instance, he foresaw and foretold that his two eldest sons would not retain control of the state. Their overthrow is a story worth telling, so far did they fall below their predecessor’s prosperity. |

| ⇑ § III | |

| Quomodo Aristobulus, qui primus diadema sumpsit, matre fratreque sublatis, moritur, quum non plus quam anno regnasset. | How Aristobulus was the first that put a diadem about his head; And after he had put his mother and brother to death, died himself, when he had reigned no more than a year. |

| 1 | |

| Patre namque mortuo, major Aristobulus, translato in regnum principatu, diadema sibi primus imposuit, quadringentis et octoginta uno annis ac tribus mensibus postquam populus in eam terram devenit, servitio quod apud Babylonios sustinuit liberatus. Fratrem vero a se secundum, Antigonum (namque illum diligere videbatur), in honore pari producebat ; alios autem vinctos custodiæ tradidit. Matremque itidem colligavit, ausam aliquid de potestate contendere. Namque hanc rerum dominam Johannes reliquerat. Eoque crudelitatis processit, ut vinctam fame necaret. | When their father died, the eldest of them, Aristobulus, turned the constitution into a monarchy, and was the first to wear a crown, 471 {(text: 481)} years and three months after the return of the nation to their own land, set free from slavery in Babylon. To the next brother, Antigonus, of whom he seemed very fond, he assigned equal honors; the rest he imprisoned in fetters. In fetters too he placed his mother, who contested his claim to supremacy, as John had left her in supreme charge, going so far in brutality as to let her die of starvation in the dungeon. |

| 2 | |

| Horum autem facinorum pœnas Antigoni fratris morte persolvit, quem plurimum amabat, quemque regni participem habebat. Nam et hunc interemit, adductus criminationibus per malevolos regni compositis. Itaque primo quidem Aristobulus dictis fidem non habebat, qui et fratrem magnipenderet, et pleraque livore fingi arbitraretur. Sed quum Antigonus ex militia clarus redisset, festis diebus quos, tabernaculis positis, Deo celebrare mos patrius exigebat, evenit eodem tempore ut adversa valetudo Aristobulum corriperet. Antigonus vero circa festorum sollemniorum finem armatis comitatus Templum ad orandum quammaxime petivit, plusque in honorem fratris ascendit ornatus. Tumque delatores nequissimi regem adeuntes, et armorum pompam, et Antigoni arrogantiam privata fortuna majorem esse criminabantur, quodque maxima caterva stipatus ut illum interficeret eo venisset, nec enim perpeti honorem solum ex regno habere, cui regnum ipsum liceat obtinere. | Vengeance overtook him in the loss of his brother Antigonus, of whom he was so fond that he had made him sharer of his royal authority. He killed even him as the result of slanders invented by unscrupulous courtiers. At first their tales were disbelieved by Aristobulus, who, as we have said, was very fond of his brother and put down most of their lies to jealousy. But when Antigonus returned with full ceremony from a campaign to attend the feast at which it is an old custom to put up tabernacles to God, it happened that Aristobulus was ill at the time. At the end of the feast Antigonus went up to the Temple with his bodyguard and in full regalia to offer prayers, mainly for his brother’s recovery. Meanwhile the unscrupulous courtiers went to the king and told him all about the escort of soldiers and the proud bearing of Antigonus, improper in a subject; he was coming, they said, with a huge force to murder him, unable to rest content with the shadow of royalty when he could grasp the substance. |

| 3 | |

| His paulatim, quamvis invitus tamen credidit Aristobulus, ac ne vel suspicari quicquam videretur, prospiciens, et ut incerta præcaveret, suos quidem satellites in quendam subterraneum et tenebrosum locum transire jubet. Ipse autem jacebat in castello, Bari ante, post autem Antonia cognominato, et ut inermi quidem parcerent, occiderent autem Antigonum, præcepit, si cum armis adiret, necnon et ipsi Antigono qui præciperent missi ut inermis veniret. Ad hæc regina satis callidum cum insidiatoribus consilium capit. Namque his qui ad eum missi fuerant persuadet ut mandata quidem regis taceant, dicant vero Antigono, quod frater audisset, arma sibi eum pulcherrima in Galilæa ornatumque bellicum fabricasse, quæ ne singulatim inspicere morbo impeditum fuisse, nunc autem, præsertim quum alio discussurus sit, libenter eum videret armatum. | These tales by degrees overcame the reluctance of Aristobulus, who took care to hide his suspicions but at the same time to guard against any unseen danger. While he himself was confined to bed in the fort at first called Baris and later Antonia, he stationed his bodyguard in one of the underground passages, with orders to leave Antigonus alone if unarmed, but to kill him if he came in arms; then he sent men to warn his brother to come unarmed. To counter this the queen contrived a very cunning plot with the conspirators. They bribed the messengers to suppress the king’s warning and tell Antigonus that his brother had heard he had secured some wonderful armor and military equipment in Galilee. Owing to his unfortunate illness he could not come and see them himself; “However,”’ he went on, “now that you are just leaving, I should very much like to see you in your outfit.” |

| 4 | |

| His auditis, Antigonus (ne quid enim male suspicaretur, fratris suadebat affectus) cum armis velut ostentatum se veniens, properabat. Sed ubi ad obscurum transitum qui « Stratonis Pyrgus » vocabatur accessit, a satellitibus interemptus est, certumque documentum præbuit omnem benevolentiam jusque naturæ calumniis cedere, nullamque optimatum affectionum tantum valere ut invidiæ perpetuo possit obsistere. | Hearing this, and aware of nothing in his brother’s disposition to make him suspect any harm, Antigonus set off in his armor to have it inspected. When he came to the dark passage called Strato’s Tower, the bodyguard killed him — convincing evidence that no natural affection is proof against slander, and that none of our better feelings are strong enough to hold out against envy indefinitely. |

| 5 | |

| ¿ In hoc autem, etiam Judam quis non recte miretur ? Essæus erat genere qui nunquam divinando aberravit, neque mentitus est. Is, Antigono transeunte per Templum, mox ut eum vidit, ad notos qui aderant exclamavit (non paucos autem discipulos sive consultores habebat), « ¡ Papæ ! Nunc mihi pulchrum est mori, quando ante me veritas interiit, mearumque prædictionum aliquod mendacium deprehensum est. Vivit enim iste Antigonus qui hodie deberet occidi. Locus autem neci ejus apud Stratonis Pyrgum fato fuerat destinatus. Et ille quidem sescentorum abhinc stadiorum intervallo distat. Horæ vero diei sunt quattuor, sed et vaticinationem tempus effugit. » Hæc locutus, senior, mæsto vultu et mente sollicita, secum multa reputabat. Et paulo post interfectus Antigonus nuntiatur, in loco subterraneo, qui eodem nomine quo maritima Cæsarea, « Stratonis Pyrgus », appellabatur, et hoc fuit quod vatem fefellit. | The incident had another surprising feature. Judas was an Essene born and bred, who had never been wrong or mistaken in any of his predictions. On this occasion, when he saw Antigonus passing through the Temple, he called out to his acquaintances — a number of his pupils were sitting there with him — “O God! The best thing now is that I should die, since truth is dead already, and one of my predictions has proved false. There, alive, is Antigonus, who was to have been killed today. The place where he was fated to the was Strato’s Tower, and that is seventy miles away {NW of Jerusalem; Latin text: 600 stades }; and it is already ten o’clock! The time has run out on my prophecy.” Having said this the old man remained lost in gloomy thoughts — and a few minutes later came the news that Antigonus had been murdered in the underground strong-point, which was actually called Strato’s Tower, like the coastal town of Cæsarea. And it was this that confused the seer. |

| 6 | |

| At vero Aristobulo confestim sceleris pænitudine morbus ingravescit, semperque facinoris cogitatione sollicitus, perturbato animo tabescebat, donec mæroris acerbitate visceribus laceratis subito sanguinem vomeret. Hunc ergo unus e servulis ejus ministerio destinatus foras efferens, providentia numinis erravit, et ubi Antigonus erat occisus, super exstantes adhuc cædis maculas cruorem interfectoris effudit. Ululatu autem eorum qui id conspexerant continuo sublato, tanquam puer de industria sanguinem illic libasset, clamor ad aures regis pervenit, causamque requirebat et, quum eam prodere nullus auderet, ad resciendum magis ardebat. Ad extremum vero minitanti vimque adhibenti, verum quod erat indicaverunt, atque ille, quum lacrimis opplesset oculos, quantumque poterat ingemuisset, hæc dixit, « Sperandum certe non erat, ut maximum Dei lumen facta mea nefaria laterent. Nam cito me ultrix cognatæ cædis justitia persequitur. ¿ Quamdiu, o corpus improbum, fratri matrique damnatam animam detinebis ? ¿ Quamdiu paulatim illis libabo sanguinem meum ? Simul totum accipiant, neque jam meorum viscerum inferias fortuna derideat. » His dictis, ilico moritur, quum non plus anno regnasset. | Aristobulus, bitterly regretting this foul crime, at once fell into a swift decline; at the thought of the murder his mind became unhinged and he wasted away, until his entrails were ruptured by his uncontrollable grief and he brought up quantities of blood. While carrying this away one of the servants waiting on him, impelled by divine providence, slipped at the very spot where Antigonus had been struck down, and on the blood-stains — still visible — of the murdered man he spilt the blood of the killer. At once a shriek went up from the spectators, as if the servant had poured the blood there on purpose. Hearing the cry the king asked the reason, and when no one dared tell him he insisted on being informed. At last by dire threats he compelled them to tell him the truth. His eyes filled with tears, and groaning with the little strength that was left he murmured: “So it is. I could not hide my unlawful deeds from God’s all-seeing eye. Swift retribution pursues me for the blood of my kinsman. How long, most shameless body, will you contain the soul that has been adjudged my mother’s and my brother’s? How long shall I pour out my blood to them, drop by drop? Let them take it all at once: let heaven mock them no more with these offerings to the dead from my entrails.” The next moment he was dead, having reigned no more than a year. |

| ⇑ § IV | |

| Quas res gesserit Alexander Jannæus, qui regnavit annos XXVII. | What actions were done by Alexander Janneus, who reigned twenty-seven years. |

| 1 | |

| Uxor vero ejus, vinculis dissolutis, regem consituit Alexandrum qui ætate major erat, et modestia præstare videbatur. Sed ille, potestatem adeptus, fratrem quidem alterum regnum appetentem occidit, alterum autem, privata vita contentum, ablatis rebus secum habebat. | His widow released his brothers and enthroned Alexander, the eldest, and seemingly the most balanced character. But on ascending the throne he executed one brother as a rival claimant: the survivor, who preferred to keep out of the public eye, he held in honor. |

| 2 | |

| Prœlium etiam cum Ptolemæo cognomento Lathyro committit, qui oppidum Asochin ceperat — et multos quidem peremit hostium, sed victoria in Ptolemæi partes propensior fuit. Postea vero quam ipse, pulsus a matre Cleopatra, discessit in Ægyptum, et Gadaram obsidione capit Alexander et castellum Amathuntis, omnium maximum quæ trans Jordanem sita erant, ubi pretiosissima quæque bonorum Theodori, filii Zenonis, habebantur. At Theodorus repente superveniens, et proprias res recipit et sarcinas regis aufert, Judæorumque fere decem milia interficit. Verum Alexander, receptis post cladem viribus, aggressus maritimas regiones, Raphiam capit et Gazam itemque Anthedonem quæ postea ab rege Herode « Agrippias » nominata est. | He also came into conflict with Ptolemy Lathyrus, who had seized the town of Asochis; he inflicted many casualties but Ptolemy had the advantage. But when Ptolemy was chased away by his mother Cleopatra and withdrew to Egypt, Alexander besieged and took Gadara and Amathus, the biggest stronghold east of the Jordan, where were stored the most valuable possessions of Zeno’s son Theodorus. But by a sudden counter-attack Theodorus not only recovered his property but captured the king’s baggage-train, killing some 10,000 Jews. However, the blow was not fatal, and Alexander turning towards the coast captured Gaza, Raphia, and Anthedon, which King Herod later renamed Agrippias. |

| 3 | |

| His autem servitio domitis, concitatur in eum festo die populus Judæorum. Nam plerumque epulæ seditiones accendunt, nec videbatur insidias posse comprimere nisi conducticios haberet auxilio Pisidas et Cilicas — nam Syros mercennarios respuebat propter ingenitam cum Judæorum discordiam. Cæsis autem supra octo milibus ex turba rebellium, Arabiæ bellum intulit. Ibique Galaaditis ac Moabitis subactis, tributoque his imposito, ad Amathunta regressus est. Quumque Theodorum metus ejus secundis successibus perculisset, castellum sine præsidio repertum funditus eruit. | After his enslavement of these towns there was a Jewish rising at one of the feasts — the usual occasion for sedition to flare up. It looked as if he would be unable to crush this conspiracy, but his foreign troops came to the rescue. These were Pisidians and Cilicians: Syrians he did not recruit as mercennaries because of their innate detestation of all Jews. After putting to the sword over 8,000 of the insurgents he attacked Arabia, overruning Gilead and Moab and imposing tribute on the inhabitants. Then returning to Amathus he found that Theodorus had taken fright at his victories and abandoned the fortress; so he demolished it. |

| 4 | |

| Mox autem congressus cum Oboda, rege Arabum, qui locum fraudi opportunum in Galaadensi regione occupaverat, captus insidiis totum amisit exercitum in vallem altissimam compulsum, atque obtritum multitudine camelorum. Ipse vero, elapsus in Hierosolymam, olim sibi gentem infensam ad novarum rerum motus magnitudine cladis accendit. Fit autem etiam tunc superior, crebrisque prœliis non minus quinquaginta milibus Judæorum per sex annos interfecit, nequaquam tamen victoriis lætabatur quoniam regni sui vires consumeret. Unde armis omissis, sermone placido cum subjectis redire in gratiam conabatur. Illi autem, inconstantiam ejus morumque varietatem in tantum oderant ut, percontanti quonam pacto eos sedare posset, dicerent, si moreretur. Nam vix etiam mortuo daturos veniam qui tam multa scelerate fecisset. Simul etiam Demetrii auxilium cui cognomen Acæro accersiverunt. Qui, quum his majorum præmiorum spe facile paruisset venissetque cum exercitu, miscentur auxiliis ejus Judæi circa Šichimam. | He next took the field against Obodas of Arabia. But the king had laid an ambush near Gaulane and Alexander fell into the trap, losing his entire army, which was crowded together at the bottom of a ravine and crushed by a mass of camels. He made good his own escape to Jerusalem, but the completeness of the disaster fanned the smouldering fires of hatred and the nation rose in revolt — only to be worsted again in a succession of battles which lasted six years and cost the lives of as many as 50,000 Jews. He had little cause to rejoice over these victories, so ruinous to his kingdom; so suspending warlike operations he attempted to reach an understanding with his subjects by persuasion. But they were still more embittered by his inconstancy and unstable behavior; and when he asked in what way he could satisfy them, they replied: “By dying; even a dead man would be hard to forgive for such monstrous crimes.” Without more ado they called on Demetrius the Untimely for help {88 B.C.}. He at once agreed — in the hope of enlarging his kingdom — and arrived with an army, joining his Jewish allies near Shechem. |

| 5 | |

| Utroque tamen Alexander mille quidem equitibus, sex autem peditum mercennariorum milibus excepit, quum haberet rex Judæis quoque prope ad decem milia bene sibi cupientium, adversæ autem partis essent equitum tria milia, peditumque milia quadraginta. Et priusquam veniretur ad manus, intercedentibus nuntiis et præconibus, reges transfugia temptabant, Demetrius quidem Alexandri mercennarios, Alexander autem Judæos qui Demetrium sequerentur, obtemperaturos sibi sperantes. Sed quum neque Judæi sacramenta, neque fidem Græci contemnerent, armis jam comminus decernebant. Superatque prœlio Demetrius, quamvis Alexandri mercennarii multa et animose et fortiter gessissent. Eventus autem pugnæ præter spem cedit utrique. Nam neque hi qui Demetrium acciverant, in partibus victoris permanserunt, et immutatæ fortunæ misericordia sex Judæorum milia se ad Alexandrum qui in montes effugerat contulerunt. Hujus inclinationis momentum Demetrius ferre non potuit, sed Alexandrum jam quidem collectis viribus prœlio sufficere ratus, omnem vero gentem ad eum transire existimans, mox inde digressus est. | The combined army was opposed by Alexander with 1,000 cavalry and an infantry force of 8,000 {(text: 6,000)} mercennaries, reinforced by loyal Jews to the number of 10,000. The other side consisted of 3,000 cavalry and 14,000 {(text: 40,000)} infantry. Before battle was joined the two kings issued proclamations intended to detach supporters from the other side, Demetrius hoping to win over Alexander’s mercennaries, Alexander Demetrius’ Jewish contingent. As the Jews would not abandon their oaths nor the Greeks their loyalty, there was nothing for it but an appeal to force. The victor in the battle was Demetrius, in spite of a magnificent display of determination and prowess by Alexander’s mercennaries. The outcome of the engagement, however, was not at all what either side had expected. Demetrius, the victor, was deserted by those who had called him in, whereas out of their pity for Alexander’s change in fortune, after fleeing to the hills, he was joined by 6,000 Jews! This swing of the pendulum was too much for Demetrius: convinced that Alexander was now fit to take the field again and that the whole nation was flocking to his standard, he withdrew. |

| 6 | |

| Non tamen reliqua multitudo ob abscessum auxiliorum simultates deposuit, bello autem assiduo tam diu cum Alexandro decertabat donec, plerisque interfectis, ceteros in Bemeselim civitatem compulit, eaque subacta in Hierosolymam captivos abduxit. Verum immoderata fecit iracundia ut crudelitas ejus ad impietatem usque procederet. Octingentis enim captivorum in media civitate crucifixis, mulieres earumque filios in conspectu matrum necavit, atque hæc potans et cum suis concubinis recubans, prospectabat. Tantus autem populum terror invasit ut etiam diversæ partis studiosi proxima nocte octo milia hominum extra totam Judæam profugerent, quorum exilii mors Alexandri finis fuit. Quum ejusmodi factis tandem ægreque regnis otium quæsisset, ab armis requievit. | The departure of their allies did not cause the rest of the people to lay aside their quarrel: they waged war unremittingly with Alexander till after very heavy losses the remnant were driven into Bemeselis; when this town fell, the survivors were taken as prisoners to Jerusalem. So unbridled was Alexander’s rage that from brutality he proceeded to impiety. Eight hundred of the prisoners he crucified in the middle of the City, then butchered their wives and children before their eyes; meanwhile cup in hand as he reclined amidst his concubines he enjoyed the spectacle. Such terror gripped the people that the next night 8,000 partisans of the opposite faction fled right out of Judæa and remained in exile till his death. By such deeds he at last gave his kingdom an uneasy peace, and hung up his weapons. |

| 7 | |

| — Caput A-4 — De bello Alexandri cum Antiocho et Areta, deque Alexandra et Hyrcano. | |

| Rursus autem fit ei turbarum initium Antiochus, qui etiam Dionysus dictus est, Demetrii quidem frater, sed eorum novissimus qui Seleucum generis auctorem habebant. Hunc enim timens qui Arabas parato bello pulsarat, totum quidem super Antipatrida montibus proximum et inter Joppes litora spatium, fossa altissima diremit. Ante fossam vero murum ædificavit excelsum, turresque ligneas ut faciles aditus obstrueret fabricavit ; nec tamen Antiochum arcere valuit. Exustis enim turribus, fossisque repletis, cum suis copiis transgressus est. Vindictaque posthabita qua deberet eum a quo prohibitus est ulcisci, protinus contendit in Arabas. Horum autem rex, in loca suæ nationi commodiora cedens, mox ad pugnam cum equitatu reversus (habebat autem numerum decem milium) imparatos ex improviso Antiochi milites invadit. Valido autem prœlio commisso, quamdiu quidem superat Antiochus, durabat ejus exercitus, quamvis eum passim Arabes trucidarent. Ubi vero procubuit (succurrendo enim victis semper in periculis aderat) omnes terga dederunt, maximaque pars eorum quum in acie tum in fuga absumitur. Reliquos autem, in vicum Cana delapsos, alimentorum penuria perire contigit, præter admodum paucos. | But fresh troubles were in store for him — the work of Antiochus Dionysius, brother of Demetrius and last heir of Seleucus. This man launched a campaign against the Arabs, alarming Alexander, who cut a deep trench stretching from the hills above Antipatris to the beach at Joppa, raising a high wall in front of the trench with wooden towers built into it to ward off attacks at the weak points. But Antiochus was not to be stopped: he burnt the towers, filled in the trench, and marched his army across. Deciding to deal later with the man who had tried to stop him, he went straight on to attack the Arabs. Their king retired to better defensive positions, then suddenly faced about with his cavalry force of 10,000 men and fell upon the army of Antiochus while it was in disarray. A bitter struggle followed. As long as Antiochus survived, his army fought on, though the Arabs were slaughtering it everywhere; when at last he fell as a result of risking his life all the time in the forefront to help his struggling soldiers, the entire line broke. Most of his army was destroyed in the engagement or in the subsequent flight; the survivors took refuge in the village of Cana, where lack of food killed off all but a handful. |

| 8 | |

| Hinc Damasceni, Ptolemæo Minnæi filio infensi, Aretam sibi sociant, Syriæque Cœles regem constituunt. Qui, bello illato Judææ, postquam pugna vicit Alexandrum, pactione discessit. Alexander autem, Pella capta, Gerasam petivit rursus, opum Theodori cupidus, triplicique ambitu circumdatis defensoribus, locum expugnavit. Necnon et Gaulanen et Seleuciam et eam quæ « Antiochi Pharanx » dicitur sub jugum mittit. Ad hæc autem capto Gamala castello validissimo ejusque præfecto Demetrio multis criminibus involuto, in Judæam regreditur, expleto in militia triennio, lætusque a gentilibus ob res prospere gestas excipitur. Belli autem requiem secutum est morbi principium. Et quoniam quartano febrium recursu fatigabatur, depulsum iri valetudinem credens, si rursus animum negotiis occupasset, intempestivæ militiæ sese dedit, et ultra vires corpus laboribus vexans, inter ipsos tumultus trigesimo et septimo regni anno moritur, | At this point the people of Damascus, through hatred of Ptolemy, son of Mennæus, brought in Aretas and made him king of Cœle Syria. He promptly marched into Judæa, defeated Alexander in battle, agreed on terms, and withdrew. Alexander took Pella and advanced against Gerasa, once more coveting Theodorus’ possessions. After shutting up the garrison within a triple wall he took the place by storm. He went on to overwhelm Gaulane and Seleucia and the “Valley of Antiochus,” and captured the strong fortress of Gamala and its commander, Demetrius, the subject of many accusations. Then he returned to Judæa, after three whole years in the field, and was warmly welcomed by the nation in view of his successes. But the end of the war proved to be the beginning of physical decay. Afflicted with third-day-recurrent malaria, he thought he could get rid of his sickness by resuming a strenuous life. He threw himself into inappropriate campaigns, and by making impossible demands on his bodily strength wore himself out completely. He died in the midst of storm and stress, after reigning for twenty-seven years. {Latin text: 37 years} |

| ⇑ § V | |

| Regnante per nonennium Alexandra, imperium penes Pharisæos. | Alexandra reigns nine years, during which time the Pharisees were the real rulers of the nation. |

| 1 | |

| idque Alexandræ conjugi suæ reliquit, Judæos ejus maxime dicto obœdientes fore non dubitans, quod longe ab ejus crudelitate discrepans, et iniquitati resistens, benevolentiam sibi populi comparasset. Neque spes eum fefellit. Namque opinione pietatis obtinuit muliercula principatum. Quippe quæ morem gentis patrium probe norat, et qui sacras leges temerassent, ab initio detestabatur. Quum autem duos filios Alexandro genitos haberet, natu quidem maximum Hyrcanum, et propter ætatem declarat pontificem et quod præterea segnior esset quam ut potestate regia molestus cuiquam videretur, regem constituit, minorem autem Aristobulum, privatum vivere maluit, quod ferventioris esset ingenii. | He had left his throne to his wife Alexandra, confident that the Jews would most readily submit to her, since by her freedom from any trace of his brutality and her constant opposition to his excesses she had gained the good-will of the people. And he was right in his expectations; woman though she was, she established her authority by her reputation for piety. She was most particular in her observance of the national customs, and offenders against the Holy Law she turned out of office. Of the two sons she had borne Alexander she appointed the elder, Hyrcanus, pontiff, in view of his age and because he was too indolent to seem to anyone to be disruptive in state affairs; the younger, Aristobulus, who was an impulsive character, she kept out of the public eye. |

| 2 | |

| Jungit autem se ejusdem mulieris dominationi quædam Judæorum factio, Pharisæi, qui præter alios pietatem colere putarentur et peritius leges interpretari ; ob eam causam magis eos suspiciebat Alexandra, divinæ religioni superstitiose deserviens. Illi autem paulatim feminæ simplici insinuati, quosvis pro sua libidine summovendo, deponendo, itemque vinciendo ac solvendo, jam procuratores habebantur, prorsus ut ipsi quidem regiis commodis fruerentur, expensas vero ac difficultates Alexandra perferret. Sed eadem mire callebat res administrare majores, itaque augendis copiis semper intenta, duplicem conflavit exercitum, neque pauca mercennaria paravit auxilia quibus non modo statum suæ gentis roboravit, sed etiam metuendam se reddidit externæ potentiæ. Imperabat autem aliis, verum Pharisæis ipsa ultro parebat. | Alongside her was the growing power of the Pharisees, a Jewish sect that appeared more pious than the rest and stricter in the interpretation of the Law. Alexandra, being superstitiously devoted to religion, paid too great heed to them and they, availing themselves more and more of the simplicity of the woman, ended by becoming the effective rulers of the state, free to banish or depose, to release or imprison, at will. In short, the privileges of royal authority were theirs, the expenses and vexations Alexandra’s. She was very shrewd, however, in making major decisions, and by regular recruiting doubled the size of her army, collecting also a large mercennary force, so that beside making her own country strong she inspired a healthy respect in foreign potentates. But while she ruled others, she herself submitted to the Pharisees. |

| 3 | |

| Denique Diogenem quendam insignem virum qui Alexandro fuerat amicissimus, interficiunt, ejus factum consilio criminati, ut octingenti (quos supra memoravi) regis jussu tollerentur in crucem. Nihilominus autem Alexandræ suadebant ut et alios, quibus auctoribus Alexander in eos fuisset concitatus, occideret. Quumque his nimia superstitione nihil abnuendum putaret, quos sibi libuisset ea specie trucidabant, donec optimus quisque periclitantium ad Aristobulum confugeret. Atque ille matri persuasit ut his propter dignitatem parceret, civitate autem pelleret quos nocentes existimaret. Igitur illi quidem, data sibi copia, per regionem dispersi sunt. Alexandra vero, in Damascum misso exercitu, quoniam Ptolemæus sine intermissione civitatem premebat, illam quidem nulla re memorabili gesta cepit. Regem autem Armeniorum Tigranem qui, admoto Ptolemaidi milite, Cleopatram circumsedebat, pactionibus donisque sollicitat. Sed illum domesticarum turbarum metus, ingresso in Armeniam Lucullo, jamdudum inde retraxerat. | Thus Diogenes, an eminent man who had been a friend of Alexander, was put to death by them, making the charge that it was on his advice that the eight hundred (whom I mentioned above) were crucified. Moreover they pressed Alexandra to execute the rest of those who had incited Alexander against them: due to her superstitious nature she thought nothing should be denied them, and under that cover they killed whom they would. The most prominent of the threatened citizens sought the aid of Aristobulus, and he persuaded his mother to spare them in view of their station, expelling them from the City if not sure of their innocence. Thus granted impunity, they scattered over the country. Alexandra dispatched an army to Damascus on the ground that Ptolemy was regularly threatening the city; the army even took it over without performing any remarkable exploit. However, while Tigranes the Armenian king was encamped before Ptolemais besieging Cleopatra, she won him over by bargaining and bribery. But fear had already withdrawn him some time before to deal with troubles at home, Lucullus having invaded Armenia. |

| 4 | |

| Inter hæc Alexandra, morbo laborante, minor ejus filius Aristobulus cum famulis suis quos multos habebat omnesque pro ætatis fervore fidissimos, universa castella obtinuit, et pecunia quam ibi reperit, conductis auxiliis, regem se declaravit. Ob hæc miserata querelas Hyrcani, mater conjugem Aristobuli cum filiis includit apud castellum quod, a septentrione Fano adjacens, Baris antea vocabatur, ut diximus, postea vero Antonia cognominata est, imperante Antonio — quemadmodum de Augusti et Agrippæ nomine Sebaste et Agrippias aliæ civitates appellatæ sunt. Ante tamen Alexandra moritur quam in Aristobulum fratris ejus Hyrcani contumelias vindicaret quem dejici regno curaverat, quod ipsa novem annos administravit. | Meanwhile Alexandra sickened; the younger son Aristobulus seized his chance, and with his numerous servants — all devoted to him because of the fervor of his youth — got all the strongholds into his power, and with the money found there raised a force of mercennaries and proclaimed himself king. This so upset Hyrcanus that his mother felt very sorry for him, and locked up the wife and children of Aristobulus in Antonia. This was a fortress adjoining the Temple on the north side; as stated already, it was first called Baris and later renamed when Antony was supreme, just as the cities of Sebaste and Agrippias were named after Sebastos (Augustus) and Agrippa. But Alexandra died before she could punish Aristobulus for the affronts to his brother Hyrcanus whom he had ejected from the kingdom which she ruled for nine years. |

| ⇑ § VI | |