DE BELLO JUDAICO

LIBER QUARTUS |

THE JEWISH WAR

BOOK FOUR |

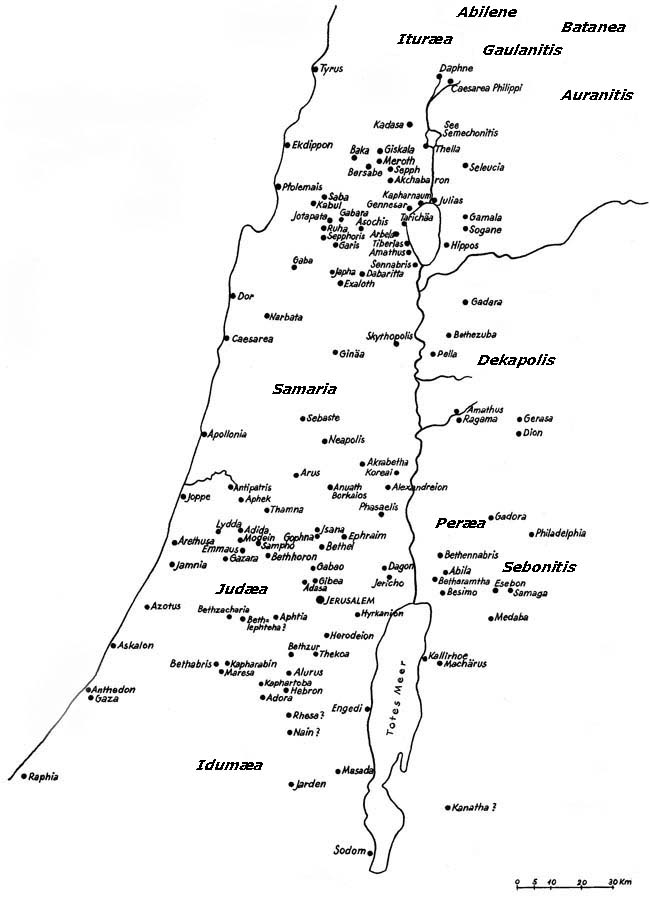

Palæstina

with locations mentioned by Josephus

|

| Book 4 |

| From the Siege of Gamala to the Coming of Titus to Besiege Jerusalem |

|

| ⇑ § I |

| Gamalæ urbis obsidio et excidium. | The siege and taking of Gamala. |

| 1 |

— Caput D-1 —

Obsidio Gamalensium. |

| Quicunque autem Galilæorum, Jotapatis excisis, Romanis defecerant, hi se ad eos postquam Taricheatæ superati sunt, applicabant, omniaque Romani castella et civitates ceperant, præter Gischalam, et qui montem Itaburium occuparant. Cum his autem rebellarat Gamala civitas, contra Taricheas posita supra lacum, quæ ad fines pertinebat Agrippæ, itemque Sogane et Seleucia. Et hæ quidem Gaulanitidis regionis erant ambæ, Sogane superioris partis, cui nomen est Gaulana, et inferioris Gamala, Seleucia vero ad lacum Semechonitem, triginta latum, et LX• stadiis longum, paludesque suas ad Daphnen usque tendentem. Quæ regio, quum alias sit deliciosa, præcipue tamen fontes habet, qui minorem (quem sic appellant) Jordanem alentes sub aureo Jovis templo in Majorem deducunt. Soganen quidem ac Seleuciam colentes, in principio defectionis Agrippa sibi fœdere sociaverat, Gamala vero ei non cedebat, freta locorum difficultate amplius quam Jotapata. |

Following the fall of Jotapata, whoever of the Galileans had stayed in rebellion against the Romans surrendered after Tarichea was defeated, and the Romans took over all the fortresses and towns except Gischala and the garrison of Mount Tabor. The city of Gamala had rebelled along with them, a place located opposite Tarichea and overlooking the lake. This town was in Agrippa’s territory, as were Sogane and Seleucia. Gamala and Sogane both belonged to Gaulanitis, Sogane being of the upper part, called Gaulana, and Gamala of the lower. Seleucia belonged to Lake Semechonitis, which is three and a half miles wide and seven long, with its marshes stretching as far as Daphne, which is a pleasant spot in general, but especially with its springs that feed what is called the Little Jordan under the golden temple of Jupiter and send it pouring into the Grand Jordan. At the beginning of the revolt Agrippa had allied the citizens of Sogane and Seleucia to himself with a treaty, but Gamala would not submit to him, relying on the difficulty of its terrain even more than Jotapata had done. |

| Jugum namque asperum, ex alto monte deductum, mediam cervicem erigit ; et ubi supereminet, in longitudinem tenditur, tantum contra declive, quantum a tergo, ut cameli similitudinem præferat ; unde nomen etiam duxit, nisi quod expressam vocabuli significationem indigenæ servare non possunt. Et a fronte quidem ac lateribus in valles invias scinditur. Pars vero qua de monte pendet, paululum difficultatem refugit. Verum et hanc partem, per obliquum excisa fossa, indigenæ inviam fecerunt. Domus autem crebræ per prona erant ædificatæ, nimioque præcipitio casuræ — similis civitas intra se decurrebat, in Meridiem vergens. Australis vero collis immensa editus altitudine, usum arcis sine muro civitati præbebat, rupesque superior ad profundam pertinens vallem. Fons autem intra muros erat, in quem oppidum desinebat. |

A rugged ridgeline descending from a high summit raises its neck up midway along its length; and, from where it peaks, it extends lengthwise as far on the foreward slope as on the backside, so that it presents some resemblance to a camel; hence the name, although the natives cannot retain the exact pronunciation of the word. Both at the front end and on its sides it is cut off by impassable canyons. On the other hand, the part which comes off of the mountain eases up on the difficulty a bit; but here too, by digging a trench across it, the inhabitants made it inaccessible. The houses, built crowded on the steep slope, were also about to fall down the exceedingly precipitous slope — it was like a city falling down on itself, facing the south. Its southwestern peak, rising to an immense height, served the city as an unwalled citadel, and its high cliff stretched down into a deep canyon. There was, however, a spring inside the walls which was the town limit. |

|

Gamala today

Looking toward the sea of Galilee

(Southeast is to the left) |

|

| 2 |

| Quamvis autem natura inexpugnabilis esset civitas, tamen etiam Josephus, quum murorum eam ambitu cingeret, fossis et cuniculis reddidit firmiorem. Ejus autem habitatores, natura quidem loci confidentiores erant quam Jotapateni, sed multo pauciores, minusque pugnaces ; situsque freti difficultate, plures se hostibus putabant. Nam plena erat civitas multis in eam, quod esset tutissima, confugientibus. Unde ab Agrippa quoque præmissis ad obsidionem, per menses septem restitere. |

Regardless of how impregnable the city was by nature, Joseph had made it even stronger with trenches and tunnels and by enclosing it with a ring of walls. Given the nature of the position, its occupants were more confident than the Jotapatans had been, but they had far fewer fighting men and less fierce ones; and relying on the difficulty of their terrain, they imagined themselves to be more numerous than the enemy. For the city was full of those who had fled there because it was the safest place. For that reason, they also resisted the besiegers sent ahead by Agrippa for seven months. |

| 3 |

| Vespasianus autem, profectus ex Ammaunte, ubi pro Tiberiade posuerat castra (Ammaus autem, si quis nomen interpretetur, « Aquæ Calidæ » vocantur ; ibi enim ejusmodi fons est, sanandis corporum vitiis idoneus) Gamalam pervenit. Et totam quidem civitatem, ita ut diximus positam, custodia circumvallare nequibat. Qua vero fieri posset, excubias collocavit, montemque occupabat superiorem in quo milites, castris — ita ut assolet — muro circumdatis, opus aggerum postremo aggrediuntur. Et a parte quidem Orientis, summo supra civitatem loco turris erat ; ubi et Quintadecima Legio, necnon et Quinta contra mediam civitatem operabatur. Fossas autem Decima replevit et valles. Inter hæc Agrippam regem, quum accessisset ad muros eorumque defensoribus de traditione loqui temptaret, funditorum quidam ad dextrum cubitum lapide percutit. Et ille quidem propterea familiaribus suis circumsæptus est. Romanos autem ira simul ob regem suique metus ad obsidionem protinus incitavit, nullum Judæos crudelitatis modum in alienigenas atque hostes prætermissum ire credentes, qui circa gentilem suum et eorum quæ ipsis conducerent suasorem tam immanes fuissent. |

Vespasian set out from Ammathus (“Hotwaters”: for there is a spring there ideal for healing physical ailments), where he had set up camp outside of Tiberias, and marched to Gamala. He was unable to encircle the entire city, situated as mentioned, with a guard. But where it was possible he posted sentries, and he took over the higher mountain where his soldiers, having surrounded their camp with the usual wall, finally undertook the construction of a siege ramp. On the eastern side there was a tower at the highest spot overlooking the city; the Fifteenth Legion worked there, and the Fifth opposite the center of the town. The Tenth filled in the trenches and ravines. At this juncture King Agrippa approached the walls and was trying to discuss terms of surrender with their defenders when one of the slingers hit him on the right elbow with a stone. He was immediately surrounded by his own men, but the Romans were spurred to press the siege both by indignation on the king’s account and out of fear for themselves: for the were convinced that the Jews, who had been so savage toward one of their own countrymen who was advising them for their own benefit, would overlook no kind of barbarity in treating foreigners and enemies. |

| 4 |

| Aggeribus autem manus multitudine, operisque consuetudine cito perfectis, machinas applicabant. Chares autem et Josephus (namque ipsi erant oppidanorum potentissimi) armatos licet metu perculsos ordinavere ; et quanquam non diu obsidionem posse sustinere arbitrabantur, quibus aqua itemque alia usui necessaria non sufficerent, adhortati tamen eos ad mœnia produxerunt. Et paulisper quidem machinis advenientibus repugnarunt. Ballistis autem tormentisque perculsi, in oppidum recesserunt. Itaque Romani tribus ex locis aggressi, murum arietibus quatiunt ; et qua dejectus fuerat, infusi magno cum armorum strepitu ac tubarum sonitu, ipsi quoque insuper ululantes cum oppidanis confligebant. |

With the large number of hands and skilled work, the siege ramps were quickly finished and the engines brought up. Chares and Joseph, the most effective leaders in the town, deployed their armed, though fear-stricken, troops; and although they did not think they could withstand the siege very long, given that water and other necessities were insufficient, they cheered them on and led them out to the walls. For a short while they beat back the advancing machines, but after being driven back by ballistas and artillery, they withdrew into the town. With that the Romans, attacking from three points, shattered the wall with their rams; and where it had been breached, they poured in with a great din of weapons and blare of trumpets and, while on top of this shouting themselves, began fighting with the townsmen. |

| Illi autem ad primos aditus interim pertinaces, Romanis ne ultra progrederentur obstabant. Ceterum vi et multitudine superati, undique ad excelsa civitatis loca fugiunt. Deinde revertentes instantibus sibi hostibus incumbunt, illosque impingendo per declivia, locorum difficultate et angustia depressos interficiebant. Romani autem, quum neque a vertice imminentibus repugnare, neque in partem aliquam evadere possent, pronos eos urgentibus hostibus, in domos hostium plano contiguas refugiebant. Sed hæ repletæ labebantur, quod pondus sustinere non poterant, unaque dejecta multas inferiores, itemque illæ alias deturbabant. Ea res plurimos Romanorum morte consumpsit. |

The latter, meanwhile, standing firm against the first waves of attackers, prevented the Romans from advancing further. Eventually, overcome by force and numbers, they fled from everywhere to the upper parts of the town. Then, as the enemy pursued them, they swung around and counterattacked. Driving them down the slopes, they killed them as they became trapped by the impediments and narrowness of the place. Unable either to fight back against those attacking them from above or to escape someplace while the enemy was pressing down on them, the Romans fled onto the enemy rooftops that were even with the ground. But these, loaded down, collapsed, since they could not hold the weight; and as one fell, it knocked down many lower ones, and those yet others. The process resulted in the deaths of a great many Romans. |

| Incerti enim quid facerent, quamvis subsīdere tecta viderent, tamen eo convolabant. Atque ita multi quidem ruinis opprimebantur ; non pauci vero subterfugientes, parte corporis mulcabantur. Plurimi autem pulvere suffocati moriebantur. Sed ea Gamalenses pro se fieri existimabant, propriaque incommoda neglegentes magis instabant ; hostesque in sua tecta urgendo compellebant. Qui vero per angustos viarum clivos cecidissent, eos telis desuper missis interficiebant. Et ruinæ quidem lapidum copiam, ferrum vero eis mortui hostes dabant. Cæsorum enim gladios auferentes, his contra semineces utebantur. Multi, jam præcumbentibus tectis, semet inde projiciendo moriebantur, tergaque dantibus ne fuga quidem facilis erat. Viarum namque ignorantia, et caligine pulveris alius alium non agnoscentes pererrabant, et circa se sternebantur. |

Completely at a loss, even when they saw the roofs falling in, they jumped onto them. Many were buried under the debris; many, while trying to escape, were physically maimed, and a great many died suffocated by the dust. The men of Gamala, viewing this as happening for their benefit and indifferent to their own losses, pressed their attack, driving and pushing the enemy onto their own roofs as the Romans fell in the steep, narrow lanes, and killing them with a rain of weapons from above. The debris furnished them with any number of stones, and the dead enemy with weapons; wrenching the swords from the fallen, they used them to finish off those who were still only half-dead. Many Romans, as the houses were starting to fall, threw themselves off them to their deaths. Not even those who were fleeing found it easy to get away; for, unacquainted with the roads and choked by the dust, they wandered around not recognizing one another, and were felled amidst their own. |

| 5 |

| Sed illi quidem vix reperto exitu, ab oppido recesserunt. Vespasianus autem, qui laborantibus semper interfuit, sævissimo dolore perculsus, quum super militem ruere civitatem videret, propriæ tuitionis oblitus, clam paulatim superiore in oppido locum prehendit, ibique inter media pericula cum paucis omnino relinquitur. Nec enim aderat tunc ei filius Titus, ad Mutianum pridem in Syriam missus. Et dare quidem terga neque tutum neque honestum sibi putabat. Rerum autem, quas ab adolescentia gesserat, ac propriæ virtutis memoria quasi Deo repletus, corpora sociorum atque arma condensat, et cum his bellum una a vertice defluens sustinebat ; et neque virorum neque telorum multitudinem formidans manebat, donec ejus animi obstinationem hostes divinam esse reputantes, impetum remiserunt. |

After barely finding the exits, they finally got out of the town. But Vespasian, who was always alongside his struggling soldiers and deeply moved by the sight of the town falling in ruins about his army, had forgotten his own safety and had stealthily and gradually taken over a position in the upper city, and was left there with a few men in the utmost peril. Not even his son Titus was with him at this time, having just been sent to Mucianus in Syria. He regarded flight as both dangerous and disgraceful; so, keeping in mind his lifetime of action and his own prowess, as though inspired by God he drew together the bodies and weapons of his troops and with them held off the wave of attack pouring down from the heights ; and heedless of the swarms of men and missiles, he stood firm until the enemy, viewing his persistence as supernatural, slackened their attacks. |

| Illis autem jam infirmius oppugnantibus, ipse pedem referens, non prius terga ostendit quam extra muros egressus est. Plurimi quidem Romani milites in ea pugna ceciderunt, et inter eos Æbutius decadarchus, vir non eo tantum prœlio quo periit, sed ubique antea fortissimus comprobatus, quique plurimis malis Judæos affecisset. In ea pugna centurio quidam, nomine Gallus, cum decem militibus in quadam domo latuit. Ejus autem habitatoribus dum cenarent, quod in Romanos fuisset consilium populi sui inter se fabulantibus, hoc audito (nam et ipse Syrus erat et hi quos secum habebat) nocte illos aggreditur ; omnibusque mactatis, ad Romanos salvus cum militibus evadit. |

With the enemy attacking less fiercely, he himself retraced his steps, not turning his back to them until he had gotten outside the walls. A great many Romans fell in that battle, among them the decurion Æbutius, a man who not only in the action in which he fell but in all earlier battles had shown heroic courage and inflicted very heavy casualties on the Jews. Also in that battle, a centurion named Gallus hid in someone’s house with ten of his soldiers. While its inhabitants were eating dinner he listened as they discussed what the plans of their people were against the Romans (for both he and his men were Syrians), and attacked them in the night. After killing them all, he made it back safely to the Romans with his soldiers. |

| 6 |

| Vespasianus autem mærore exercitum adversis casibus videns, quodque nullam interim tantam experti fuerant cladem, hujusque rei magis eos pudere, quod solum ducem in periculis reliquissent, consolandos putabat, de se quidem nihil dicens, ne quem vel initio culpasse videretur, oportere autem inquiens quæ communia essent fortiter ferre, naturam belli cogitantes, quodque nusquam eveniat sine cruore victoria, iterumque habeat fortuna regressum ; multis tunc Judæorum milibus interfectis, exiguam pro his stĭpem se inimicæ pependisse fortunæ ; atque ut jactantium esse nimis secundis rebus insolescere, ita esse ignavorum in offensionibus trepidare. |

But Vespasian, viewing his army with sadness in its misfortunes — because they had meanwhile experienced no such disaster and, even more, were ashamed of having left their commander in the midst of danger —, undertook to console them. He said nothing about himself so that he would not seem to be blaming them at the outset, but said it was necessary to bear what was commonplace with courage, remembering the nature of war, that victory never happened without bloodshed, and that Fortune would come back again. After many thousands of Jews had been killed, a small fee had been paid to an inimical Fortune for them. And just as it was typical of boasters to become haughty due to good luck, so it was typical of cowards to become fearful in setbacks. |

| « Velox enim est », inquit, « in utrumque mutatio, et ille vir fortis habetur cujus sobrius erit animus in rebus quoque infeliciter gestis, ut idem scilicet maneat, rectis consiliis peccata corrigens. Quanquam ea, quæ nunc acciderunt, neque mollitia nostra, neque Judæorum virtus effecit. Nam et illis pugnæ melioris, et nobis deterioris, causa fuit difficultas locorum. Qua in re nimirum quis reprehenderit alacritatis vestræ temeritatem. Nam quum hostes in excelsiora loca refugissent, manus continere debuistis neque in summo vertice constituta sequi pericula sed, capta inferiori civitate, paulatim eos, qui refugerant, ad tutiorem vobis et stabilem pugnam revocare. |

“For change happens quickly on both sides, and the man who maintains a cool head even in reverses so that he remains the same, correcting his mistakes with the right strategies, is the one who is considered courageous. Moreover the things that have just happened were caused neither by our own weakness nor the valor of the Jews. For the cause of the battle going better for them and worse for us was the difficulty of the ground. Hence one might, of course, blame the rashness of your eagerness: for when the enemy fled to the higher ground, you ought to have held back and not gone after the dangers located at the top. Rather, having captured the lower town, you should have gradually enticed those who had fled to a battle on sure footing, one safer for you. |

| « Nunc autem, immoderata festinatione vincendi, quam id incaute fieret, non curastis. Inconsultus autem et furibundus impetus belli a Romanis alienus est, qui cuncta ordine peritiaque perficimus, Barbarisque conveniens, et quo Judæi maxime possĭdentur. Oportet igitur nos ad propriam virtutem recurrere atque indignæ offensioni irasci potius quam mærore. Optimum autem quisque de sua manu solacium quærat. Ita enim fiet, ut et amissos ulciscamur, et in eos e quibus perempti sunt, vindicemus. Ipse autem, ita ut nunc feci, experiar, æque ac vos, pugnando primus ad bella pergere, et novissimus inde discedere. » |

“Instead, in your unrestrained rush for victory, you did not think about how reckless it would be. But thoughtless and irrational attacks in war are foreign to us Romans, who accomplish everything through order and methodically; such things are typical of the barbarians, actions in whose grip the Jews above all are. So we have to return to our own strengths and be moved to anger by an unworthy defeat rather than by regret. Let everyone seek his best solace from his own right arm. In that way we will avenge our lost men and punish those by whom they were killed. I myself, as I have just done, will try, just as you, to advance, fighting, into battle first, and to be the last to leave it.” |

| 7 |

| Ille quidem his dictis recreavit exercitum. At Gamalenses, bene gesta re, paulisper animos erexere, quæ, nulla ratione, magna magnificeque provenerat. Mox autem, reputantes ablatam sibi esse fœderis spem, quodque minime possent effugere (jam enim victus eos defecerat) vehementer dolebant, animosque remiserant. Nec tamen quatenus valebant, salutem suam neglegebant, sed tam disturbatas partes muri qui erant fortissimi, quam integras ceteri, amplexi custodiebant ; Romanis autem construentibus aggeres, iterumque tentantibus irruptionem, multi ex civitate per valles devias qua nulli custodes erant et per cloacas diffugiebant ; eos qui metu ne caperentur ibi remanserant, inopia consumebat. Solis enim undique alimenta qui pugnare possent congerebantur. |

With this address, Vespasian revived his army. Meanwhile, for a while the people of Gamala had their spirits raised by the fortunate event which had unaccountably turned out great and magnificently; but soon, realizing that the hope of an accommodation had been lost, and that they could not escape (for their provisions had already given out), they became very depressed and lost heart. Still, to the extent that they could, they did not neglect their own protective measures: the strongest men took over and guarded the breached parts of the wall while the others did so for the intact parts. But as the Romans built the siege ramps higher and tried new assaults, many of them fled the city through uncharted ravines where there were no guards and through sewers. Those who remained out of fear of being captured starved to death from lack of provisions, since food from all quarters was taken for only those who could fight. |

| 8 |

| Sed illi quidem in hujusmodi calamitatibus perdurabant. | It was amidst such adversities that they continued to hold out. |

— Caput D-2 —

Itaburius mons occupatur a Placido. |

| Vespasianus autem, inter curas obsidionis, subsicivum opus aggreditur adversus eos qui montem Itaburium occupaverant, inter Campum Magnum et Scythopolim situm. Cujus altitudo quidem XXX• stadiis consurgens, Septentrionali tractu inaccessa est. In vertice autem, XX• stadiorum planities patet, tota muro circumdata. Hunc autem tantum ambitum quadraginta diebus ædificaverat Josephus, et alias ei materias, et aquas suggerentibus locis inferioribus. Solam enim incolæ pluvialem habebant. |

Despite this, Vespasian, while managing the siege, undertook a secondary operation against those who had taken over Mount Tabor, midway between the Great Plain and Scythopolis. This mountain rises to 20,000 feet {(Latin: 30 stades)}, inaccessible on the northern side; the top is a plateau three miles {(20 stades)} long with a wall all around. {(The mountain is actually 613m [2,011 ft] above sea level, and 460m [1,509 ft] above the valley; the plateau is about 1200m [~3900 ft or ¾ mile] x 400m [~1312 or ¼ mile].)} Josephus had built this huge rampart in forty days, obtaining his material and even his water supply from the lower elevations. (For the occupants had only rainwater.) |

|

Mt. Tabor from the air

(Looking northeastward) |

|

| Magna igitur in eo multitudine congregata, Vespasianus Placidum cum sescentis equitibus mittit. Huic autem subeundi quidem montis ratio nulla erat. Multos autem fœderis ac veniæ spe hortabatur ad pacem, et descendebant ad eum ipsi quoque insidias molientes. Nam et Placidus eo studio mitissime cum his loquebatur, ut eos in planitie caperet. Illique tanquam dictis obœdientes ad eum veniebant, ut incautum aggrederentur. Vicit tamen astutia Placidi. Cœpto enim a Judæis prœlio, assimulat fugam ; et postquam insequentes ad magnam partem campi pellexit, reflectit in eos equitum manus ; plurimisque in terga versis, aliquos interfecit. Semotam vero multitudinem ceteram ab ascensu prohibet. Itaque alii quidem, Itaburio relicto, in Hierosolymam refugiebant. Indigenæ autem, fide accepta, quod eis aqua defecerat, et se et montem Placido tradiderunt. |

On this plateau, vast numbers had gathered; so Vespasian dispatched Placidus with six hundred horsemen. There was, however, no way for him to climb the mountain. So he called on the majority to make peace, offering the hope of a treaty and pardon. They came down to him, contriving their own ambush to match his. Placidus, after all, had engaged in very accommodating conversations with them in order to capture them on the plain; they came down to him as though complying with his terms, so as to attack him unawares. However, it was Placidus’ cunning that won: for when the Jews began the fight, he pretended to flee; and after enticing his pursuers far onto the plain, he turned his horsemen about and routed most of the enemy, killing a number of them. He cut the remaining mass of them off from a reascent. Others, abandoning Tabor, fled to Jerusalem; the natives, their safety being guaranteed and their water having failed, handed themselves and the mountain over to Placidus. |

| 9 |

— Caput D-3 —

Excidium Gamalæ. |

| Apud Gamalam vero degentium audacissimi quisque, fuga dispersi, latebant ; imbelles autem fame corrumpebantur. At vero pugnantium manus obsidionem sustinebat, donec evenit secundo et vigesimo die mensis Octobris, ut tres ex Decimaquinta Legione milites circa matutinas vigilias editissimam præ ceteris turrim quæ in sua parte fuerat subirent, eamque occulte suffoderent, quum appositi ei custodes neque adeuntes eos (nox enim erat) nec postquam adiere, sensissent. Iidem autem milites, cavendo ne strepitus fieret, quinque saxis durissimis evolutis, resiliunt ; subitoque turris cum magno fragore decidit, unaque custodes præcipitantur. |

Of the residents at Gamala, all the bolder ones, scattering in flight, went into hiding, while the noncombatants died of starvation. The band of combatants sustained the siege until, on the twenty-second day of October {(actually, November 9)}, it came about that, in the pre-dawn watch, three soldiers of the Fifteenth Legion crept up to the highest of the towers in their sector and secretly undermined it. The sentries assigned to it failed to observe them (for it was night) either during or after their arrival. Making sure there was no noise, the same soldiers rolled away the five heaviest stones and jumped clear. The tower fell suddenly with a resounding crash, and the sentries with it. |

| At vero qui per alias custodias erant, perturbati fugiebant, multosque evadere ausos peremere Romani ; inter quos etiam Josephum, super dirutam muri partem quidam jaculo percussum interfecit. Intus autem in civitate degentibus, sono concussis, multus erat pavor atque discursus, tanquam omnes essent hostes ingressi. Tuncque Chares ægrotus et jacens defecit, quum timoris magnitudo morbum ejus plurimum juvisset ad mortem. Romani tamen, prioris cladis memores, usque ad vigesimam et tertiam diem supradicti mensis oppidum non sunt ingressi. |

Those at the other sentry-stations fled in terror; many made a bold effort to break through but were cut down by the Romans, among them Joseph, who was killed on the breach in the wall by someone with a javelin. Shaken by the crash, those residing in the city panicked and ran in all directions as if all of the enemy had already broken in. At that moment Chares, sick and in bed, expired, due to the fact that the intensity of fear had greatly helped his sickness make him die. The Romans, however, mindful of their earlier failure, did not invade the town until the twenty-third of the above-mentioned month. |

| 10 |

| Titus autem (jam enim aderat), indignatione vulneris quod Romanos se absente perculerat, ducentis equitibus præter pedites lectis, otiose in civitatem introivit. Eoque prætergresso, vigiles quidem ubi senserunt, ad arma cum clamore properabant. Cognito autem intus constituti ejus ingressu, alii raptis liberis, trahentes etiam conjuges, cum ululatu et exclamationibus in arcem refugiebant ; alii Tito occurrentes, sine intermissione trucidabantur ; qui vero prohibiti essent in arcem recurrere, nescii quid facerent, Romanorum præsidiis incidebant. |

Then Titus (who was now present), enraged at the blow which had struck the Romans during his absence, entered the city without a problem with two hundred cavalrymen in addition to elite infantry. After he had already gotten past them, the sentries discovered it and rushed yelling to their weapons. When the people inside became aware of his invasion, some, grabbing their children and dragging along their spouses, fled screaming and shouting to the citadel, while others attacked Titus and were instantly cut down. Those who were prevented from running to the citadel, at a loss for what to do, fell into the hands of the Roman camp guards. |

| Ubique autem infinitus erat morientium gemitus, perque prona loca effusus cruor totum oppidum diluebat. In eos autem qui arcem occupaverant, omnem Vespasianus induxit exercitum. Erat autem saxosus et accessu difficillimus vertex, in immensum editus, et undique circum rupium multitudine præceps ; unde Romanos ad se adeuntes partim telis, partim saxis devolutis arcebant Judæi, quum ipsos in excelso loco positos nullæ sagittæ contingerent. |

The unceasing groans of the dying were everywhere, and the blood pouring down the slopes inundated the whole city. Vespasian then concentrated his whole army on those who had taken over the citadel. But the peak was rocky and extremely difficult of access, immensely high and totally encircled with precipices of massed rocks. As a result, the Jews fended off the Romans coming at them partly by using weapons and partly by rolling rocks down on them, whereas arrows could not reach the Jews themselves in their high perch. |

| Verum ad eorum interitum divino munere quodam turbo exoritur, Romanorum quidem tela in eos ferens, ipsorum autem a Romanis repellens et obliqua traducens, ut neque in præruptis consistere propter violentiam flatus possent, quum nihil esset immobile, neque hostes ad se accedentes videre. Itaque supergressi Romani, eos circumveniunt, alios quidem repugnantes antecapiebant, alios manus dantes. In omnes autem vehementius sæviebant, illorum memoria quos in primo aggressu perdiderant. Multi autem undique circumclusi, desperatione salutis, filios et conjuges et semet ipsos in vallem præcipites dabant quæ sub arce in profundum patebat. |

But to their downfall, by some kind of supernatural intervention a storm arose, carrying the Roman shafts up to them but repelling their own and turning them aside, making it so that they could neither stand on the precipitous ledges on account of the force of the wind where nothing would stay stable, nor see the oncoming enemy. Thus the Romans came up and encircled them, penning in both some who were fighting back and others who were surrendering. Regardless, they raged furiously against them all, remembering those whom the Jews had killed in the first attack. Despairing of escape and hemmed in everywhere, many flung their wives, their children and even themselves headlong into the canyon which yawned far below beneath the citadel. |

| Evenit autem ut ipsorum in se, qui capti fuerant, immanitate lenior exsisteret iracundia Romanorum. Ab his enim quattuor milia perempta sunt ; qui vero se præcipitaverunt, quinque milia sunt reperti. Neque quisquam præter duas mulieres salvus evasit. Quæ sorores erant, Philippi filiæ ; qui Philippus Jachimo genitus erat, insigni viro, et qui sub Agrippa rege dux exercitus fuerat. Servatæ sunt autem, quod excidii tempore Romanorum impetum latuere. Nec enim vel infantibus pepercere, quorum multos singuli raptos ex arce projiciebant. Gamala quidem hoc modo excisa est, tertio et vigesimo die mensis Octobris, quæ vigesimo et primo die mensis Septembris cœperat rebellare. |

In fact, the fury of the Romans turned out to be less savage than that of the captured Jews against themselves. For 4,000 fell by Roman swords, but those who jumped to their deaths were found to be over 5,000. {(Modern estimates are that there were 3,000 - 4,000 inhabitants at the start of the revolt.)} There were no survivors except for two women, nieces of Philip, son of Jacimus, a man of note who had been the commander-in-chief of King Agrippa’s army. They survived because at the time of the destruction they hid from the attacking Romans, who did not even spare infants, of whom individual soldiers seized many and flung them from the citadel. It was in this way that Gamala was annihilated on the twenty-third of October, after having begun its rebellion on the twenty-first of September. |

|

| ⇑ § II |

Gischalorum deditio, quum Joannes

se fuga Hierosolyma recepisset. | The surrender of Gischala ; while John flies away from it to Jerusalem. |

| 1 |

— Caput D-4 —

Gischala a Tito capitur. |

| Jamque solum Gischala oppidulum Galilææ restabat indomitum ; cujus multitudo pacis studio tenebatur, quod erant plerique agricolæ, spemque suam semper in fructibus collocaverant. Non parvæ autem manus latrocinalis permixtione corrupti erant, quo morbo etiam nonnulli civium laborabant. Hos autem ad defectionem impellebat atque conflabat Leviæ cujusdam filius, nomine Joannes, homo veneficus et fallax, variusque moribus, et immoderata sperare promptus, miroque modo quæ sperasset efficiens, atque omnibus jam cognitus, quod affectandæ sibi potentiæ causa bellum amaret. Huic apud Gischala seditiosorum turba parebat, quorum causa populus, etiam legatos fortasse de traditione missurus, Romanorum tamen congressum in parte belli præstolabatur. |

Only Gischala, a little town in Galilee, was left unreduced. The inhabitants were interested in peace — for the most part they were farmers whose only concern lay in their harvests; but they had been corrupted by the infiltration of a large gang of brigands, and some of the townsmen were suffering from the disease. They were driven and incited to revolt by John, son of Levi, a confidence man and liar, of variable behavior, inclined toward intemperate expectations and accomplishing them in surprising ways. And it was known to everyone that he was fond of war for the sake of seizing power. The insurgent crowd in Gischala obeyed him, as a result of which the people, perhaps even about to send envoys to surrender, were now waiting to clash with the Romans in war mode. |

| At Vespasiauus contra hos quidem Titum cum equitibus mille, Decimam vero Legionem circa Scythopolim mittit ; cum reliquis autem duabus Cæsaream ipse regreditur, dandam his ex labore continuo requiem putans, ex civitatum copiis ; eorumque corpora, itemque animos ad futura certamina existimans esse refovendos. Nec enim exiguum sibi laborem superesse de Hierosolymis prævidebat, quæ et regalis esset Civitas, et cunctæ nationi præstaret. His autem qui ex bello fugissent in eam confluentibus, etiam naturalis munitio, itemque murorum ejus constructio, non minimam ei sollicitudinem comparabat, quum virorum spiritum et audaciam, et sine muris inexpugnabilem esse cogitaret ; ob eamque rem milites, velut athletas, ante certamina oportere curari. |

To crush this opposition, Vespasian dispatched Titus with 1,000 horse, sending the Tenth Legion to Scythopolis. He himself returned to Cæsarea with the other two, thinking to give them a rest with urban resources after their unintermittent struggles and in the belief that their bodies and spirits needed to be refreshed for the coming battles. For he foresaw that it was no small task that was left at Jerusalem, which was the royal City and the head of the entire race. Given that refugees from the war had been flowing into her, its natural fortification and the construction of its walls instilled in him more than a little worry when he considered the fact that the aggressiveness and audacity of its men were unconquerable even without walls. It was therefore necessary to train his soldiers like wrestlers before a contest. |

| 2 |

| Tito autem civitas Gischala (equitando enim ad eam accesserat) aggressione capi facilis videbatur. Sciens tamen quod, ea vi capta, passim a militibus populus absumeretur (namque satiatus erat ipse jam cædibus), miserans multitudinem etiam ipse sine ullo discrimine cum nocentibus intereuntem, pactione magis subigere civitatem volebat. Itaque plenis hominum muris, quorum plerique perditæ factionis erant, mirari se ait, quonam freti consilio, cunctis jam civitatibus captis, illi soli Romanorum arma operirentur, quum viderent multo quidem munitiora oppida uno impetu fuisse subversa, securos autem fortunis suis potiri qui Romanorum dextris credidissent ; quas quidem etiam nunc illis ait se porrigere, neque ob insolentiam suscensere, quia spei libertatis ignoscendum putaret — non tamen, etiamsi quis impossibilia velle perseveraret. Quod si dictis humanissimis non paruissent fidemque dextris non habuissent, experturos arma crudelia ; jam jamque cognituros esse, mœnia sua ludum fore machinis Romanorum, quibus fidentes, soli ex Galilæis sese ostentarent arrogantes esse captivos. |

Upon riding up to the town of Gischala, Titus saw that it would be easy to take by storm. Knowing, however, that with the capture of the city by force the population everywhere would be annihilated by the soldiers, whereas he himself was sick and tired of slaughter and had pity for a populace which would perish quite indiscriminately with the guilty, he preferred, rather, to take over the town by treaty. So, given that the walls were crowded with men who were mainly of the criminal gang, he said he wondered what idea they were relying on when, with all the other towns subjugated, they alone were still waiting for a Roman attack at the same time that they saw far stronger towns overthrown by a single assault, and while all those who had entrusted themselves to Roman power were enjoying their own property in safety. He said he was now offering them the same thing and would not take offense at their truculence because he thought he ought to forgive their hope of freedom — but not if someone continued to demand the impossible. So if they did not submit to his generous proposals and accept his sincere offers, they would experience the mercilessness of his weapons; they would immediately learn the fact that the Roman engines would make a game of their walls — and by depending on them they would show themselves to be the only Galilæans who were arrogant captives. |

| 3 |

| His dictis popularium quidem neminem non modo respondere, sed ne ad murum quidem licuit ascendere, quia totum latrones occupaverant ; et custodes erant portis appositi, ne quis vel ad fœdus prodiret, vel equitum quenquam in civitatem reciperet. Joannes autem accipere se condiciones ait, et aut persuasurum, aut necessitatem belli renītentibus adhibiturum. Illum tamen diem Judæorum Legi oportere concedi. Quoniam sicut arma movere, ita etiam de pace convenire nefas haberent. Nam et Romanos scire, quod ab omni cessaret opere dierum septem circuitio, quam si temerassent, non minus coactos quam qui cogerent piaculum commissuros, ipsumque Titum ; nullum enim illi ex mora esse dispendium formidandum ; quod unius noctis spatium præter fugæ consilium ceperit — præsertim quum id observare circumsedentem nemo prohibeat ? |

To these overtures none of the townspeople was allowed to make any reply nor even to mount the wall, because the brigands had completely taken it over; and guards had been posted at the gates to prevent anyone from going out to treaty negotiations or from allowing any of the cavalry into the city. But John replied that he would accept the conditions and either persuade or use the force of war on the resisters. Still, it was necessary to obey the Law of the Jews for that particular day. Because they considered it equally forbidden to take to arms and to negotiate for peace. For even the Romans knew that the seventh day of the week entailed withdrawal from all activity; if they broke that rule, those who were forced would be committing a sin no less than those who compelled them, and than Titus himself. He should fear no harm because of the delay; what stratagem could the period of a single night produce besides that of flight — especially when no one prevented him from surrounding the town and watching? |

| Sibi autem magnum esse lucrum, nulla in re despicere patrios mores, et illum decere, qui pacem non sperantibus indulget, legem quoque servare servatis. His Titum Joannes fallere conabatur, non tantum pro septimi diei religione, quantum pro sua salute sollicitus ; verebatur autem, ne statim capta civitate, solus destitueretur, qui totam in nocte ac fuga vitæ spem collocasset. Verum profecto Dei nutu, in excidium Hierosolymorum Joannem salvum esse cupientis, factum est, ut non solum indutiarum causationem Titus admitteret, verumetiam in superiori parte oppidi castra poneret, ad Cydœssam, qui mediterraneus est Tyriorum vicus validissimus, Galilæis semper exosus. Habebat enim habitantium multitudinem munitionemque firmam ut subsidia in dissensionibus cum hac natione. |

But it would be a great benefit to the Jews not to infringe their ancestral customs in any way. And it would also be becoming of Titus, who was showing forbearance toward those who were not expecting peace, to respect the Law of those thus spared. It was with such pleas that John, who was less anxious about observance of the seventh day than about his own safety, tried to fool Titus. He was afraid that, immediately after the capture of the city he, who was putting all hope of saving his life in darkness and flight, would be left alone in the lurch. But clearly it was by the will of God, who desired to preserve John to bring destruction on Jerusalem, that Titus not only accepted this pretext for the suspension of hostilities, but even pitched his camp on the upper side of the town, at Cydœssa. This is a strong inland village of the Tyrians, always hostile to the Galilæans. It had a large population and strong defenses as resources in its struggle against this nation. |

| 4 |

| Nocte autem Joannes, quum nullas Romanorum excubias circa oppidum videret, arrepta occasione, non solum his quos circa se habebat armatos, sed etiam senioribus plurimis cum familiis abductis, in Hierosolymam fugiebat. Sed usque ad vigesimum quidem stadium fieri posse videbatur, ut mulieres ac pueros, aliamque multitudinem secum duceret, homo quem captivitatis, itemque salutis metus urgeret. Ultra vero procedente eo, relinquebantur ; et oriebatur atrox remanentium fletus. Quanto enim quisque longius a suis aberat, tanto propiorem se hostibus esse credebat. |

In the night John, seeing no Roman sentries around the town, seized his chance and, taking with him not only his surrounding armed retinue but a large number of older men with their families, fled towards Jerusalem. Up until a bit over two miles it seemed possible for this man, driven by fear of capture and for his life, to drag along the women, children and the rest of the crowd; but as he pressed on further they were abandoned, and a terrible lament arose from those thus left behind. For the further each one was from his own kith and kin, the nearer he imagined himself to the enemy. |

| Jamque affore qui se caperent existimantes, necessario pavitabant ; et ad strepitum quem ipsorum cursus faciebat, assidue respectabant, velut instantibus quos fugissent ; multique simul ruebant, et circa viam plurimos certamen præcedentium conterebat. Miserabile autem feminarum et infantium erat exitium. Aut si quam jactarent vocem, nonnullæ viros aut propinquos, ut se operirentur, orabant. Sed Joannis exhortatio superabat, ut seipsos servarent inclamantis ; eoque confugerent, unde pro remanentibus etiam si raperentur, pœnas a Romanis peterent. Multitudo quidem eorum, qui fugerant, ut cuique virium fuit, cito dispersa est. |

Believing that their captors were already amidst them, they necessarily panicked and constantly looked back when the heard the footsteps of their companions, as if their pursuers were upon them. Many were rushing at the same time and along the way trampled a great many of those who were preceding them in the race. The destruction of the women and children was pitiable; or if they loudly yelled something, some pleaded for their husbands or male relatives to wait for them. But John’s exhortations, as he cried out that every man should save himself, won out; they should flee to the place from which, even if those left behind were captured, they would take vengeance on the Romans. Thus the mass of fugitives quickly lengthened out in accordance with each one’s stamina. |

| 5 |

| Luce vero facta Titus ad muros aderat, fœderis causa ; populus autem portis ei patefactis, cum conjugibus occurrentes, tanquam benemerito, et qui custodia civitatem liberasset, acclamabant ; simulque Joannis fugam significantes, ut et sibi parceret obsecrabant et eos qui ex novarum rerum cupidis reliqui superessent ulcisceretur. Ille autem, precibus populi postulatus, equitum partem, ut Joannem persequeretur, mittit. Sed eum quidem occupare nequivere, quod antequam venerant, in Hierosolymam sese receperat. Una vero fugientium prope ad duo milia perimunt ; mulieres ac pueros paulo minus quam tria milia circumactos reducunt. |

When dawn came, Titus was at the wall to conclude the treaty. The people, opening the gates to him and coming forward with their families, hailed him as a benefactor who had delivered the town from captivity. Simultaneously informing him of John’s flight, they besought him to spare them and punish the remaining rebels. Titus, though importuned by the prayers of the people, sent a detachment of horse to pursue John; but they were unable to overtake him because before they had come he had escaped into Jerusalem. Still, they did kill close to two thousand of those who had fled with him, and rounded up and brought back a little fewer than 3,000 women and children. |

| Titus autem indigne ferebat non statim a Joanne pœnas fraudis exactas ; irato vero animo satis esse, quod spe deciderat, ad solacium putans captivorum et qui trucidati fuerant multitudinem, in oppidum cum favore ingreditur ; jussisque militibus minimam muri partem jure possessionis abrumpere, minitando magis quam puniendo reprimebat perturbatæ civitatis auctores. Multos enim propter odia domestica vel proprias inimicitias, delatores innocentiæ fore credebat, si dignos pœna discerneret ; meliusque noxium relinquere metu suspensum quam immeritum quenquam cum eo perdere, existimabat ; |

Titus was vexed at his failure to inflict immediate punishment on John for his deception; but his infuriated state of mind resulting from the disappointment was appeased by considering as solace the large number of captives and of those who had been slaughtered. So he entered the town amid applause and, ordering his men to tear down a small section of the wall in token of capture, used threats rather than punishment to subdue the disruptors of the town’s peace. For he believed that many would turn informers of the innocent out of personal animosity and private enmity if he were to pick out those worthy of punishment; it was better to leave the guilty suspended in fear than to execute any guiltless person with them; |

| illum enim fortassis modestiorem futurum, vel metu supplicii, vel et quod erubesceret præteritorum criminum venia ; sine causa vero morientium pœnas nullo modo corrigi posse. Præsidiis tamen civitatem circumdedit quæ tam novarum rerum studiosos compescerent quam pro pace sentientes, quos ibi relicturus erat, majore fiducia firmarent. Galilæa quidem tota, postquam multo sudore Romanos exercuit, hoc modo subacta est. |

for the guilty man would perhaps become more civil either from fear of punishment or even because he was ashamed as a result of the pardon he had received for his past misdeeds; but for those put to death without cause there could be no redress. However, he surrounded the town with a garrison which would restrain the rebellious as well as give more confidence to the peaceable citizens he was about to leave behind there. Thus the whole of Galilee was subdued, after having cost the Romans a great deal of sweat. |

|

| ⇑ § III |

| De Joanne Gischaleno. Deque Zelotis et Anano pontifice : et quomodo inter se dissidebant. | Concerning John of Gischala. Concerning the Zealots and the High Priest Ananus ; As Also How the Jews Raise Seditions One against Another [in Jerusalem]. |

| 1 |

— Caput D-5 —

Hierosolymitani excidii initium. |

| Apud Hierosolymam vero, ad Joannis introitum, omnis populus erat effusus et circa singulos qui una confugerant, numerosa turba collecti, quas foris clades experti essent percontabantur. Illorum autem fervens quidem adhuc atque interruptus anhelitus necessitatem significabat. Verumtamen in malis quoque sibi arrogabant, non Romanorum vim fugisse dicentes, sed sponte venisse, ut cum his ex tutiori loco pugnarent. Inconsultorum enim atque inutilium esse hominum, incaute pro Gischalis et invalidis oppidulis periclitari, quum arma vigoremque oporteat pro metropoli suscipere atque servare ; significando tamen excidium Gischalorum — etiam quam dicebant honestam discessionem suam — ut multi fugam esse intelligerent prodiderunt. |

On John’s arrival there the whole population turned out and, with large crowds collecting around each of his companions in flight, they asked for news of the disasters happening outside. Their hot and gasping breath betrayed their desperate state, but they still blustered in their sorry plight, declaring that they had not fled from the Romans but had come of their own accord to fight with them on safer ground. It would have been an act of senseless and futile men to risk their lives rashly in a hopeless struggle for Gischala and other weak little towns, when they ought to save and use their arms and energy for the Cult Center. But by mentioning the fall of Gischala — what they even called their honorable withdrawal — they gave it away, so that many understood it to be a rout. |

| Auditis autem quæ captivi pertulere, non mediocris populum perturbatio tenuit, magnumque id esse argumentum proprii reputabant excidii. At Joannes eorum quidem quos fugientes reliquerat causa minus erubescebat, singulos autem circumiens spe ad bellum incitabat, infirmitatem Romanorum asserens, propriasque vires extollens, et imperitorum ea cavillatione inscitiam decipiens, quod etiamsi pennas sumerent, nunquam Hierosolymorum mœnia transgrederentur Romani qui pro Galiæorum vicis tanta mala pertulissent, atque in eorum muris machinas contrivissent. |

When, however, what the captives had suffered became known, utter dismay seized the people, who saw in it a powerful omen of their own doom. John himself, quite unconcerned for the fate of those he had left behind, went around using hope to whip them up for war, asserting that Roman power was feeble, exaggerating their own power, and deceiving them by ridiculing the ignorance of the inexperienced. He claimed that not even if the Romans grew wings could they ever get over the wall of Jerusalem, after having endured such problems with Galilæan villages and worn out their engines against their walls. |

| 2 |

| His ejus dictis magna quidem corrumpebatur juvenum manus. Prudentiorum autem atque seniorum nemo erat qui non, futura prospiciens, velut jam perditam Civitatem lugeret. Et populus quidem in ea confusione tunc erat. At vero per territorium manus agrestium, ante seditionem quæ Hierosolymis orta est, discordare jam cœperat. (Titus enim a Gischala Cæsaream, Vespasianus autem a Cæsarea Jamniam et Azotum profectus, utramque subegit ; impositisque illic præsidiis, revertebatur, maximam ducens eorum multitudinem qui se fœdere sociaverant.) |

With this sort of talk a large part of the youth was corrupted. But of the sensible, older men there was not one who, viewing the future, did not mourn for the City as if it had already perished. The citizenry, indeed, found itself in a state of confusion at that time. But throughout the countryside the bulk of the rural people had begun to feud even before strife arose in Jerusalem. (Titus meanwhile had left Gischala for Cæsarea, and Vespasian had marched from Cæsarea to Jamnia and Azotus, reducing both. After garrisoning them, he returned at the head of a mass of those who had pledged him their allegiance.) |

| Singulas autem civitates tumultus bellumque intestinum exagitabat : quantumque a Romanis respirassent, in semetipsos manus vertebant, quum inter amatores belli ac pacis cupidos esset sæva contentio ; dudumque discordium pertinacia primo inter domos accenderetur, deinde inter se amicissimi populi dissiderent ; et ad similia volentes quisque conveniens aperte jam coacta multitudine rebellaret. Itaque dissensiones quidem apud omnes erant, novitatis autem armorumque cupientes senibus ac sobriis juventute atque audacia præstabant. Primo autem indigenarum singuli prædari cœperunt ; deinde ex composito confertis cuneis per territorium latrocinabantur, ut quod ad crudelitatem atque injustitiam spectat, nihil a Romanis gentiles abessent ; atque ipsis qui vastabantur, illatum a Romanis excidium levius videretur. |

Turmoil and civil war were tearing up individual towns : and as soon as the Romans gave them a breathing space, they turned their hands against one another, so that between advocates of war and lovers of peace there was a savage quarrel. Originally, in the home, intransigent discord had been bursting into flame for some time; then groups extremly friendly to one another became antagonists and, coming together with like-minded types and merging into organized bodies, they started fighting. Discord reigned everywhere, the revolutionaries and belligerents with the boldness of youth overriding the old and sensible. At first, individual groups began plundering; then, organizing themselves into compact units, they extended their brigandage throughout the country, so that in lawless brutality they differed in no way from the Romans — indeed, to the victims it seemed the ruination inflicted by the Romans was easier to bear. |

| 3 |

| Civitatum vero custodes, partim quia defatigari pigeret, partim odio nationis, aut nulli aut minimo erant male affectis auxilio ; donec rapinarum satietate undique congregati collegiorum latrocinalium principes, atque in agmen conflati, Hierosolymis irrumpunt. Quæ Civitas a nullo regebatur, et more patrio gentiles omnes sine observatione recipiebant, tunc præcipue cunctis existimantibus universos qui superinfluerent adjumento ex benevolentia venire. Quæ quidem res, etiam sine dissensione, Civitatem postea pessundedit, eo quod iners et inutilis multitudo quæ pugnacibus sufficere possent alimenta consumpsit, hisque præter bellum etiam seditionem famemque comparavit. |

The garrisons of the towns, partly because it was a bother to go through the trouble, and partly out of hatred toward our people, were of no or minimal help to the victims. Until finally the leaders of the robber cartels, coming together from everywhere after being sated with rapine, and merging into an army, broke into Jerusalem. The City was governed by no one, and by age-old custom they admitted anyone of Jewish race without scrutiny, and especially at this juncture everyone thought that all those who were pouring in were coming out of kindness to help. It was this very thing that, quite apart from the faction-fighting, ultimately destroyed the City; for an idle and useless mob consumed supplies which could have been adequate for the fighting men and, in addition to war, afflicted them with sedition and starvation. |

| 4 |

| Aliique latrones ex agris eo transgressi, ac multo sævioribus quos intus invenere sociati, nullum atrox facinus intermittebant. Nec enim rapinis et exspoliationibus metiebantur audaciam, sed usque ad cædes ruebant, non clam neque per noctem aut quoslibet homines, verum luce palam nobilissimos quosque adoriendo. Nam primum Antipam, regii generis virum, et adeo potentissimum civium, ut etiam publicos thesauros fidei suæ permissos haberet, comprehensum custodiæ tradiderunt ; post hunc etiam Leviam quendam, insignem virum, et Sopham filium Raguëlis, regalis similiter utrumque familiæ, omnesque præterea qui præstare aliis videbantur. Gravis autem metus populum possidebat, et velut capta Civitate, salutem propriam quisque curabat. |

Other brigands from the countryside moved into the City and, joining forces with the far more ruthless ones they found inside, left no hideous crime uncommitted. They did not limit their insolence to pillage and plunder, but went as far as murder, not secretly or by night or against just anyone, but openly by day, attacking all the most eminent. First they seized and imprisoned Antipas, a member of the royal family and a citizen so very important that he held all the public funds committed to his trust. Next came a certain Levias, an eminent man, and Sophas, son of Raguel, both of royal blood — then beyond that all who were prominent. A deep fear seized the people and, as if the City had already been captured, everyone thought only of his own safety. |

| 5 |

| Illi autem clausorum vinculis non fuere contenti, neque tutum arbitrabantur ea potentia viros diutius custodire, nam et ipsos et domos eorum non paucis viris frequentari, ac per hoc ad ulciscendum esse idoneos, et præterea rebellaturum fortasse populum, iniquitate commotum. Decreto igitur eos occidi, mittunt quendam de suo numero Joannem ad cædes promptissimum qui lingua patria Dorcadis filius dicebatur ; eumque alii decem armati gladiis secuti ad carcerem, ibi quos repperissent interficiunt. Fingebant autem hujus immanissimi sceleris causam, cum Romanis eos de traditione Civitatis collocutos fuisse, communisque libertatis proditores interemisse dicebant, prorsus ut audacia sua tanquam servatores Civitatis, ac bene de ea meriti, gloriarentur. |

The terrorists were not satisfied with imprisoning their captives and considered it unsafe to keep men of such power incarcerated for long, as both those individuals themselves and their households were constantly visited by quite a few men who were, hence, also able to avenge them; and on top of that, the people, incensed by the injustice, might revolt. So they decided to murder the prisoners, sending in from among their number the one best suited for murder, a certain John, who was called in the vernacular “the son of Dorcas” {(“the son of Gazelle”)} He and ten others went into the prison sword in hand and slew those they found there. For this hideous crime they then invented the excuse that the slain had conferred with the Romans about surrendering Jerusalem, and said they had perished as traitors of the common freedom. In fact, they boasted of their temerity as if they were saviors of the City and had rendered great services to her. |

| 6 |

| Evenit autem populum quidem ad hoc humilitatis ac formidinis, illos vero insolentiæ progredi, ut in eorum esset arbitrio etiam pontificum designatio. Denique familiis abrogatis unde per successionem pontifices creabantur, incognitos atque ignobiles constituebant ut impiorum facinorum socios haberent. Nam qui supra meritum summos honores adepti erant, his obœdiebant necessario qui sibi eos præstiterant, quoniam et dignitate præditos variis machinis fictisque sermonibus committebant, opportunitatem sibi ex eorum qui se prohibere poterant contentione captantes donec, hominum persecutione satiati, in divinitatem contumelias transtulerunt, pedibusque pollutis in Sanctum Locum introire cœperunt. |

The result was that the people became so submissive and fearful, and the terrorists so insolent, that even the appointment of pontiffs lay in their power. Dispensing with the families from which pontiffs were successively appointed, they put in place unknown and lowborn people so they would have partners in their impious crimes; those who without deserving it attained the highest office necessarily obeyed those who had given it to them. Moreover, they set the authorities against one another with various tricks and invented tales, taking advantage of the bickerings of those who could have stopped them until, sated with their persecution of men, they shifted their insolence to God and entered the Sanctuary with their polluted feet. |

| 7 |

| Jam vero populo contra eos concitato (namque auctor erat Ananus, ævo maximus pontificum, itemque sapientissimus, et qui fortassis Civitatem conservasset, si insidiatorum manus potuisset effugere), illi Templum Dei adversus populi turbam, castellum ac profugium sibi fecere, quod pro domicilio habebant tyrannidis. Acerbis autem malis admiscebatur etiam cavillatio, quæ præ ceteris eorum factis erat dolori. Temptando enim quanto metu populus teneretur, suasque vires explorando, sorte pontifices creare conati sunt, quum his (ut diximus) ex familiis successio deberetur. Huic autem fraudi mos antiquus obtendebatur. Nam et olim sorte pontificatum deferri solitum fuisse dicebant. Re autem vera, legis erat abrogatio firmioris per eos qui ad potentiam designandorum magistratuum licentiam compararent. |

The populace was now enraged at them, urged on by the oldest of the pontiffs, Ananus, and also the wisest, who might have saved the City if he had been able to escape the hands of the plotters. These made the Temple of God their stronghold and refuge from popular upheavals, which they occupied as a headquarters of tyranny. Along with their bitter misdeeds they also combined ridicule, which was more hurtful than their other actions. For to see just how much fear the people were held by, and to try out their own power, they attempted to appoint pontiffs by lot, even though, as we have said, the succession was supposed to come from the families. Ancient custom was given as the pretext for this fraud; for they said that once upon a time the pontificate had been conferred by lot. In reality it was an abrogation of established law by those who were developing illegitimate means to power by appointing magistrates. |

| 8 |

| Itaque una sacratarum tribuum accita, quæ Eniachin appellatur, pontificem sortiebantur ; casuque sors exit homini, per quem maxime eorum iniquitas demonstrata est, Phani cuidam, filio Samuëlis, ex vico Aphthasi, non solum non ex pontificibus orto, sed aperte quid esset pontificatus, propter rusticitatem penitus nescienti. Denique invitum eum rure abstractum, ut in scæna fieri solet, aliena ornavere persona, indutumque sacra veste, quid facere deberet, subito instituebant ; ludumque et jocum esse tantum nefas arbitrabantur. Ceteri vero sacerdotes, procul spectantes ludibrio Legem haberi, lacrimas vix tenebant, honoresque sacrorum solvi graviter ingemebant. |

So summoning one of the sacerdotal clans, one called “Eniachin,” they drew lots for a pontiff. By chance the lot fell to a man through whom their evil was made most manifest, a certain Phanias {(= Pinehas)}, son of Samuel, of the village of Aphthas, a man not only not descended from pontiffs, but due to his rusticity manifestly completely ignorant of what the pontificate might be. Anyway, dragging him willy-nilly from the country, they placed him, as typically on a stage, in a role other than his own and, robing him in sacred vestments, instructed him on the spur of the moment what to do. They considered this grotesque sacrilege a game and a joke, but the other priests, from a distance watching the Law be held up to ridicule, were hardly able to hold back their tears and expressed deep grief over this dissolution of the sacred rites. |

| 9 |

| Populus autem hanc eorum audaciam non tulit, sed omnes quasi ad deponendam tyrannidem animos intenderant. Nam qui præstare ceteris videbantur, Gorion, Josephi filius, et Simeon Gamaliëlis, tam singulos circumeuntes quam simul universos in contionibus hortabantur, quo tandem aliquando libertatis corruptores ultum irent, Sanctumque Locum ab hominibus sceleratis purgare properarent. Pontifices etiam probatissimi, Gamala quidem, filius Jesu, Anani autem Ananus, populum frequenter in cœtibus exprobrando ejus segnitiem, contra Zelotas excitaverunt. Ita enim se ipsi vocabant, uti bonarum professionum æmuli, ac non qui pessimam facinorum immanitatem superassent. |

The people, however, could no longer take this arrogance of theirs: one and all now aimed at deposing what amounted to a tyranny. Those who seemed to be more eminent than others — Gorion, son of Joseph, and Simeon, son of Gamaliel — went around appealing to individuals as well as to the whole people to take vengeance against the destroyers of freedom, and to make haste to purge the Sanctuary of these defiled men. The most respected of the pontiffs, Gamaliel, son of Jesus, and Ananus, son of Ananus, held meetings at which they frequently reproached the people for their indifference and incited them against the Zealots; for it was “Zealots” that they called themselves, as if they were men zealous for good works, and not those who were uppermost in the worst of criminal enormities. |

| 10 |

| Itaque in contionem populo congregato, cunctisque indignantibus occupationes Sanctorum, itemque rapinas et cædes, nondum autem promptis ad ulciscendum propterea quod inexpugnabiles (id enim verum erat) Zelotæ putabantur, stans inter eos medius Ananus, et ad Legem crebro respectans, quum lacrimis opplesset oculos, « Equidem », inquit, « mori potius deberem quam Dei domicilium videre tantis refertum piaculis, atque inaccessa et Sancta Loca sceleratorum pedibus frequentari ; verum tamen sacerdotali veste amictus, et sanctissimum venerabilium nominum ferens, vivo atque animæ amore teneor nec pro senectute quidem mea mortem sustinens gloriosam. |

Thus, with the people gathered at a meeting and everyone enraged at the occupation of the Sanctuary as well as at the rapine and murders, but not yet ready to take vengeance because the Zealots were thought to be impregnable (which was true), Ananus stood up in their midst and, looking repeatedly back at the Law with his eyes full of tears, began thus: “I certainly ought rather to have died than see the house of God filled with such terrible sacrileges, and the unapproachable and Holy Places crowded with the feet of the reprobate! And yet I — clothed as I am with the priestly vestments and bearing the most sacred of venerable names — am alive, and am kept so by the love of life; I do not accept what would be a glorious death for my old age. |

| « Igitur solus ibo, et tanquam in solitudine animam meam solam dabo pro Deo. ¿ Nam quid opus est vivere in populo clades suas minime sentiente, et apud quos mala præsentia nemo prohibet ? Siquidem spoliati patimini ac verberati reticetis, et ne gemitu quidem aperto quisquam prosequitur interemptos. O acerbam dominationem! ¿ Quid de tyrannis querar ? ¿ Nunquid non a vobis vestra potentia nutriti sunt ? ¿ Nunquid non despectis qui primi erant, quum adhuc pauci essent, vos dum tacetis, plures eos fecistis ? ¿ Atque illis armatis quiescentes, in vosmetipsos arma vertistis ? ¿ Quum primos eorum conatus oportuisset infringi, quando cognatos conviciis appetebant ? |

“And so I’ll go alone and, as though in solitude, I’ll give my life alone for God. What is the use of living among people who absolutely fail to perceive their own calamities and among whom no one stops the evildoing? Especially when you allow yourselves to be plundered, and stay silent when beaten, and no one reacts to murders with even a groan. What bitter tyranny! But why complain about the tyrants? Were they not nourished by you with your power? Did you yourselves not, by disdaining the first ones, when they were still few, while you stood by silently, multiply their numbers? And, being apathetic while they were arming, did you not turn those arms against yourselves? At the same time that you ought to have halted their first attempts, when they were launching verbal assaults against your compatriots? |

| « Vos autem neglegendo, ad deprædationem noxios irritastis quia vastatarum ædium nulla ratio erat. Itaque jam domini ipsi rapiebantur, eisque, quum per mediam Civitatem traherentur, nemo erat auxilio. Illi autem a vobis proditos etiam vinculis affecere ; non dico quales et quantos, sed quod non accusatos, indemnatos, vinctos nemo adjuvit. Restabat eosdem videre trucidari. Hoc etiam vidimus, velut e grege brutorum animalium quum præcipua quæque duceretur hostia, ne vocem quidem quisquam emisit, nedum dexteram movit. ¿ Patiemini ergo, patiemini etiam Sancta conculcari videntes ? ¿ Quumque omnes audaciæ gradus nefariis hominibus subjeceritis, eorum præstantiam reveremini ? |

“But by being indifferent you encouraged these criminals to plunder because there was no accounting for the pillaged houses. So they seized their owners too, and when they were dragged through the middle of the City no one helped them. The criminals put them, betrayed by you, into chains — I will not say of what character or how many they were. Uncharged, uncondemned, they were imprisoned without a soul coming to their rescue. As a result we saw them slaughtered. We also saw how, as from a herd of dumb beasts where all the finest are led to a sacrifice, no one raised even a word, let alone moved his right arm! Will you tolerate it then, will you tolerate it, when you watch even your Sanctuary being trampled underfoot? And since all of you yourselves have laid the stepping stones of insolence beneath the feet of evil men, are you going to pay homage to their overlordship? |

| « Nunc enim profecto ad majora procederent, si quid majus quod everterent inveniretur. Tenetur quidem munitissimus Civitatis locus, Fanum appellatione, re arx quædam sive castellum. Tanta igitur contra vos tyrannide munita, et inimicis super verticem positis, ut videtis, ¿ quid cogitatis, aut quibus vestras sententias applicatis ? ¿ An Romanos expectatis, ut Sanctis vestris opitulentur ? Ita quidem se nostræ Civitatis habent res, eoque jam calamitatis ventum est, ut misereatur nostri etiam hostis. ¿ Non exsurgetis, o miseri, respectisque vulneribus vestris, quod etiam feras bestias facere videmus, non ultum ibitis in hos qui vos percussere ? ¿ Non suas quisque recordabitur clades et, ante oculos positis quæ pertulerit, ad ultionem animos acuet ? |

“Why, by now they would undoubtedly have proceded to even greater heights if they had found anything greater to overthrow! They have seized the strongest place in the City, called a Temple, but in fact a kind of citadel or fort; Now that the tyranny against you has been fortified and the enemy is positioned over your heads, what is going through your minds, or to whom are you addressing your thoughts? Are you waiting for the Romans to recover your Holy Places? The situation of our City has now gotten to the point of disaster where even the enemy pities us. Will you not rise up, you pitiable people, and, recognizing your wounds, as we see even the wild beasts do, wreak vengeance against those who are striking you? Why doesn’t everyone remember his own personal devastation, set before his eyes what he has suffered, and whet his appetite for vengeance? |

| « Periit apud vos (ni fallor) affectionum omnium carissima, et maxime naturalis, cupiditas libertatis. Servitutis autem ac dominorum amantes facti sumus, tanquam subjugari a majoribus didicerimus. Atque illi quidem multa et maxima bella, ut in libertate viverent, pertulerunt, ne aut Ægyptiorum aut Medorum potentiæ cederent, dummodo ne facerent quæ juberentur. ¿ Et quid opus est de majoribus loqui ? Hoc ipsum bellum quod cum Romanis nunc gerimus — verum commode an, contra, incommode non referam — palam, ¿ quid habet causæ, nisi libertatem ? ¿ Ergo qui dominis totius orbis servire non patimur, gentiles nostros ferimus tyrannos ? Quanquam externis obœdientes, ad fortunam semel id referunt cujus injuria victi sunt. At vero pessimis suorum cedere, ignavorum est, et cupientium serviendi. |

Unless I am mistaken, the dearest and greatest natural desire for freedom has died out among you. We have become lovers of slavery and of overlords, as though we learned subjugation from our ancestors. They, in contrast, endured many huge wars in order to live in freedom, so that they would not have to submit to the power of the Egyptians or the Medes, or have to do what they were ordered. But why talk about our forefathers? This very war which we are currently waging with the Romans — I will not talk about whether it is advantageous or, on the contrary, disadvantageous — openly, what is its object if not freedom? So we who will not suffer being slaves to the masters of the whole world, are we to put up with tyrants of our own race? Admittedly, those who are in submission to foreign powers can attribute it to fortune by whose injustice they were conquered, but to submit to criminals of one’s own nation is characteristic of degenerates and of people who want to be slaves. |

| « Ad hæc autem, quia Romanorum mentio facta est, non vos celabo, quid dum loquor intervenerit, mentemque retraxerit ; quod etiam si ab his capti fuerimus (absit autem hujus dicti periculum) nihil acerbius experiemur quam isti nos affecere. ¿ Quo pacto autem non lacrimis dignum sit, illorum quidem in Templo donaria cernere, gentilium vero spolia, qui nobilitatem hujus maximæ omnium Civitatis compilaverunt, eosque viros trucidatos videri, quibus etiam illi post victoriam obtemperassent ? |

“Having mentioned the Romans, I will make no secret of what occurred to me as I was speaking and turned my thoughts to that issue. Even if we were captured by them — heaven forbid such a disaster — we would not experience anything worse than what those people have subjected us to. How would it not be deserving of tears to see the donations of the Romans in the Temple, and then also the plunder of compatriots who have pillaged the nobles of this City, the greatest of all, and for those noblemen to be seen massacred whom even the Romans would have respected after their victory? |

| « ¿ Et Romanos quidem nunquam transgredi ausos esse limitem profanorum, aut sacratæ quicquam consuetudinis præterire, sanctorum autem ambitum, quamvis procul aspectum, perhorrescere, quosdam vero in his locis natos ac sub nostris moribus educatos, et qui Judæi vocentur, inter media Sancta deambulare, manibus adhuc suis gentili cæde calentibus ? ¿ Quis igitur externum bellum metuat, ex comparatione domestici ? Multo nobis æquior est hostis. Nam si proprie rebus sunt aptanda vocabula, fortasse reperietur legum quidem conservatores nobis fuisse Romanos, hostes vero intus haberi. Verum hos insidiatores libertatis exitio deberi, neque facinorum eorum dignum excogitari posse supplicium, certum est, idemque omnibus vobis, et ante orationem meam esse persuasum, atque ipsis vos rebus quas pertulistis, in eos esse commotos. |

“And to see the Romans never having overstepped the boundary of the profane or infringed on any sacred custom, but shuddering in awe upon seeing the precinct of the Sanctuary from however far away, while men born in this country, brought up in our customs and called Jews, stroll around the Inner Sanctuary, their own hands still steaming with the slaughter of their countrymen? So who would fear a foreign war in comparison with a civil one? The enemy is much more just to us. For, if we are to call things by their right names, we might well find that the Romans are the protectors of our Law, and its enemies are inside the City! Indeed, it is certain that these destroyers of freedom deserve death, but that no punishment could be devised worthy of their crimes, and that all of you were persuaded of this even before my speech, and were enraged against them because of the very things which you yourselves have suffered. |

| « Plerique autem fortasse multitudinem eorum, atque audaciam reformidant, et præterea quod in loco superiore consistunt. Sed hæc, ut vestra neglegentia conflata sunt, ita nunc magis proficient si morabimur. Nam et numerus illorum in dies singulos alitur, eo quod nequissimus quisque ad similes profugiat ; et audaciam plus accendit, quod nullum adhuc ejus impedimentum intervenit ; locoque superiore utentur, et quidem cum apparatu, si eis tempus demus. |

Possibly most of you are terrified by their numbers and their temerity, and also because they are on higher ground. But just as these things have come about through your negligence, they will now intensify all the more if we delay. For their numbers are growing by the day, since all the worst types are joining their likes; also, the fact that there is still no obstruction to block them fires their audacity all the more; and they will naturally make use of their commanding position, and with materiel as well, if we give them the time. |

| « Quod si adversus eos ire cœperimus, humiliores erunt, mihi credite, conscientia ; et celsioris loci beneficium reputatio scelerum perdet. Fortasse autem Dei pariter spreta majestas in ipsos tela retorserit, suisque missilibus consumentur impii. Videant nos tantummodo, et dejecti sunt — quanquam pulchrum est ut, etiam si quod periculum immineat, pro sacris januis moriamur ac, si non liberis et conjugibus, pro Deo tamen ejusque Sanctis animas profundamus. Præbebo autem manum atque sententiam ; et neque consilium vobis ullum deerit ad cautionem, neque me corpori meo parcere videbitis. » |

“But if we begin to go against them, believe me, they will be humbled by their own consciences, and the advantage of their higher position will be nullified by the recognition of their crimes. Perhaps the fact that they have spurned the majesty of God will turn their weapons back on them, and those ungodly men will be destroyed by their own missiles. Only let them see us and they are finished! And in any case it is glorious — even if there should be some threat of danger — to die before the sacred portals and to give our lives, if not for our children and wives, then for God and his Holy Places. I will offer you my hand and my counsel; and you will not lack any strategy for your safety, nor will you see me spare my own physical being.” |

| 11 |

| His Ananus contra Zelotas populum hortabatur, non quidem nesciens jam expugnari vix posse propter multitudinem ac juventutum animorumque pertinaciam, multoque magis propter conscientiam commissorum — nec enim concessum iri veniam his quæ perpetraverant sperabant ; verumtamen quidvis perpeti præstabilius existimabant, quam in tanta rerum perturbatione Rempublicam neglegere. Populus autem duci se clamabat in eos contra quos rogabatur, et ad subeunda pericula quisque promptus erat. |

With these words Anaus roused the people against the Zelots — not, indeed, being ignorant of the fact that now they could hardly be overcome on account of their numbers and the pertinacity of the youths and their spirit, but even much more because of the consciousness of their crimes, given that they would not expect that pardon would be granted for what they had perpetrated. Nevertheless his hearers thought it was preferable to endure anything rather than to leave the state in neglect amid such confusion. The people for their part clamored for him to lead them against the enemies he had denounced, every man being most anxious to be in the forefront of the fight. |

| 12 |