DE BELLO JUDAICO

LIBER SECUNDUS |

THE JEWISH WAR

BOOK TWO |

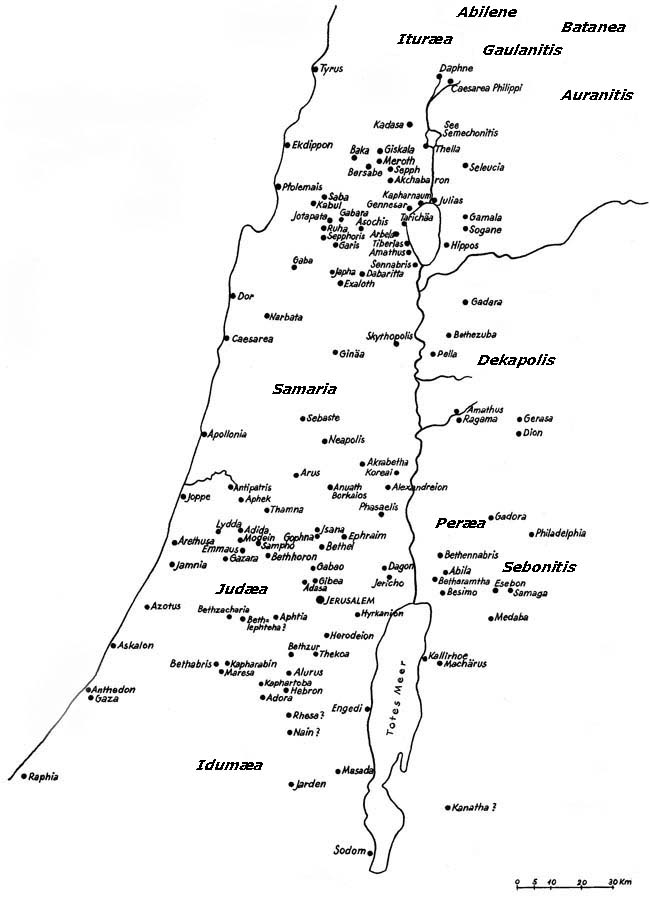

Palæstina

with locations mentioned by Josephus

|

|

| Book 2 |

| From the Death of Herod till Vespasian was sent to subdue the Jews by Nero. |

|

| ⇑ § I |

Archelaus epulum funebre

populo pro Herode dat. Mox,

seditione a multitudine excitata,

milites in eos immittit,

qui ad tria hominum milia

interficiunt. | Archelaus makes a funeral feast for the people, on the account of Herod. After which a great tumult is raised by the multitude and he sends the soldiers out upon them, who destroy about three thousand of them. |

| 1 |

— Caput B-1 —

De successoribus Herodis, et ultione direptæ aureæ Aquilæ. |

| Turbarum autem novarum principium fuit Archelao Romam proficiscendi necessitas. Diebus enim septem in lugendo patrem consumptis, epulisque feralibus prolixe populo exhibitis (hic autem mos apud Judæos necessario multos ad inopiam redegit ; nam qui neglexerat, impius æstimabatur), candida veste indutus procedit ad Templum. Ibique variis favoribus exceptus a plebe, ipse quoque in excelso tribunali, solioque aureo resĭdens, humanissime vulgus admisit ; eisque et quod sepulturam patris sedulo curavissent, gratias egit, et quod sibi quasi certo jam regi, magnos honores habuissent. Verum se tamen, ait, non potestate solum interim, sed etiam ipso regis nomine temperare, donec a Cæsare sibi confirmata fuerit successio, qui etiam testamento, rerum esset omnium dominus constitutus. Idcirco enim se apud Hierichunta voluntati exercitus restitisse, quum sibi diadema voluisset imponere. Ceterum pro alacritate ac benevolentia, æque militibus ac populo plenam se vicissitudinem relaturum, si ab his quorum etiam esset imperium certus rex declaratus fuisset ; studiumque sibi esse, ut erga illos rebus omnibus patre melior appararet. |

Archelaus was involved in fresh disturbances by the necessity of visiting Rome. He had spent a week mourning his father, and had provided the funeral feast for the populace on the most lavish scale — a custom which is the ruin of many Jews: they are obliged to feed the populace to escape the charge of impiety. Now he changed into white garments and proceeded to the Temple, where the people received him with varied acclamations. In reply he waved to the crowd from a golden throne on a raised platform, and thanked them heartily for the great pains they had taken with his father’s funeral, and the respect they had already shown to himself as if he were already established as king. However, for the present he was going to forbear assuming the royal power or even the title until his succession had been confirmed by Cæsar, who by the terms of Herod’s will was in supreme control. At Jericho also, when the army had tried to set the crown on his head, he had refused it; however, for their enthusiastic loyalty he would render full payment to soldiers and people alike as soon as the supreme authorities had established him as king; he would endeavor in every way to show himself kinder to them than his father had been. |

| 2 |

| His gavisa multitudo statim ejus mentem magnis temptare petitionibus cœpit. Namque alii tributa levari, alii vectigalia tolli, quidam solvi custodias acclamabant. Cunctis autem postulatis in gratiam populi facile annuebat Archelaus. Deinde celebratis hostiis, cum Amicis erat in epulis. Ecce autem subito post meridiem congregati non pauci novarum rerum studiosi, ubi communis luctus de rege cessavit, propria lamenta suscipiunt, flentes eorum casum quos propter abscisam ex porta templi aquilam auream Herodes morte damnaverat. Dolor autem non occultus erat, sed clarissimis questibus, fletuque justo et planctu Civitas personabat, virorum causa videlicet quos pro Templo ac legibus patriis interiisse dicebant. Eorum autem mortis pœnas ab illis quos Herodes pecunia donasset repetendas esse clamitabant : ac primum, quem is constituerat pontificem rejiciendum, aliumque pietate præstantem, magisque purum optari debere. |

This promise delighted the crowd, who at once tested his sincerity by making large demands. Some clamored for a lightening of direct taxation, some for the abolition of purchase-tax, others for the release of prisoners. He promptly agreed to every demand in his anxiety to appease the mob. Then he offered sacrifices and sat down to a banquet with the Associates. But in the afternoon — lo and behold! — a number of men with revolutionary ideas gathered and began lamentations of their own when the public mourning for the late king was over, bewailing the deaths of those who had been executed by Herod for cutting down the golden eagle from the gate of the Sanctuary. These were not secret lamentations but very loud wails, formal crying, and breastbeating, that resounded throughout the whole City, as they were for men who, they said, had died for the laws of their country and for the Sanctuary. To avenge them they clamored for the punishment of those whom Herod had monetarily rewarded, and above all the removal of the man whom he had appointed pontiff; for it was their duty to choose a man of great piety and with cleaner hands. |

| 3 |

| Quibus etsi movebatur Archelaus ad ultionem, tamen eum profectionis festinatio continebat, metuentem, ne sibi multitudinem reddidisset inimicam, motu ejus impediretur. Quamobrem monendo magis quam vi experiebatur sedare turbatos : missoque magistro militum, ut quiescerent, eos rogabat. Sed illum seditionis auctores, ubi ad Templum venit, priusquam verbum faceret, lapidibus proturbarunt : et aliis post eum mulcendi sui gratia missis — multos enim legabat Archelaus — iracunde omnia responderunt : neque si numero aucti fuissent, otiosi fore videbantur. Itaque instante azymorum die festo qui apud Judæos « Pascha » vocitatur, plurima victimarum copia plenus, infinita quidem ad Templum ex agris multitudo religionis causa descendit, quum illi qui sophistas lugebant in Templo consisterent, nutrimenta seditioni quærentes. Hoc autem metu Archelaus, antequam omnem populum morbus iste corrumperet, cohortem militum et tribunum, qui etiam seditionis principes comprehenderent, eo dirigit ; contra quos omne vulgus excitatum multos lapidum ictibus interfecit : saucius vero tribunus vix elabitur. Et illi quidem statim, veluti nihil mali actum esset, ad celebranda sacra conversi sunt. Sed Archelao sine cæde jam multitudo comprimi non posse videbatur. Quamobrem totum illis immisit exercitum, pedites per Civitatem simul omnes, equitesque per campum : qui quum sacrificiis occupatos singulos invasissent, prope ad tria milia hominum occidunt ; reliquam vero manum per montes proximos disjecerunt. Præcones autem sequebantur Archelaum, jussu ejus unumquemque, ut domum recederet, admonendo. Itaque cuncti, neglecta diei festivitate, abiere. |

This infuriated Archelaus, but he held his hand in view of the urgency to begin his journey, fearing that if he aroused the hostility of the populace the consequent disturbance might delay his departure. He therefore tried to quiet the rebels by persuasion rather than by force, and privately sent his commander-in-chief to ask them to desist. The officer came to them in the Temple, but before he could utter a word the rioters stoned him and drove him away, doing the same to others whom Archelaus sent after him to secure quiet. To every appeal — for Archelaus sent many emissaries to them — they made a furious response, and it was evident that they would not be idle if their numbers were enlarged. Moreover, the Feast of Unleavened Bread was approaching — known to the Jews as the “Passover,” and celebrated with sacrifices on a vast scale — and there was a huge influx from the country for the festival. Meanwhile those who were bewailing the dead rabbis massed in the Temple, seeking fuel for sedition. This frightened Archelaus who, to prevent the disease from infecting the whole population, sent a tribune with his cohort to restrain by force the leaders of the sedition. Their approach infuriated the whole mob, who stoned and killed many; the tribune, wounded, barely escaped. Then right away, as if nothing bad had occurred, they turned to sacrifice. Archelaus realized that the crowd could no longer be restrained without bloodshed; so he sent his whole army against them, the infantry in a body through the City, the cavalry through the countryside. As all the men were sacrificing the soldiers suddenly swooped on them, killing about 3,000, and scattered the remainder among the neighboring hills. Archelaus’ heralds followed him, ordering everyone to go home; and home they all went, abandoning the Feast. |

|

| ⇑ § II |

Archelaus

cum magna cognatorum turba

Romam proficiscitur.

Ibi ab Antipatro

apud Augustum accusatus

causam vincit,

defendente eum Nicolao. | Archelaus goes to Rome with a great number of his kindred. He is there accused before Cæsar by Antipater ; but is superior to his accusers in judgment by the means of that defense which Nicolaus made for him. |

| 1 |

| Ipse autem cum matre, necnon et Popla et Ptolemæo et Nicolao amicis, ad mare descendit, relicto Philippo regni procuratore, itemque rerum familiarium curatore. Una vero egressa est cum filiis suis Salome, fratrisque regis filii generque, specie velut Archelao ad obtinendam successionem adjumento futuri, certa vero causa, quæ contra leges in Templum admissa fuerant, delaturi. |

Archelaus with his mother and three of his Associates — Poplas, Ptolemy and Nicolas — went down to the sea, leaving Philip as governor of the Palace and custodian of his property. He was accompanied by Salome and her children and by the late king’s nephews and sons-in-law, who professed the intention of supporting his claim to the throne, but whose real purpose was to denounce him for his lawless actions in the Temple. |

| 2 |

| Interea fit illis Cæsareæ obviam Sabinus, Syriæ procurator, ad Judæam veniens, ad pecunias custodiendas Herodis, quem ulterius progredi Varus inhibuit, multis accitus Archelai precibus, intercedente Ptolemæo. Et tunc quidem Sabinus in gratiam Vari, neque ad arces venire properavit, neque thesauros paternæ pecuniæ clausit Archelao sed, usque ad cognitionem Cæsaris se otiosum esse pollicitus, apud Cæsaream commorabatur. Postea vero quam sibi obstantium unus Antiochiam petiit, alter — hoc est, Archelaus — Romam navigavit, mature profectus in Hierosolymam, regiam tenet. Custodumque principibus itemque dispensatoribus evocatis, rationes pecuniarum discutere conabatur, et arces occupare temptabat. Non tamen immemores Archelai mandatorum custodes erant, sed in observando singula quæque perseverabant, causam custodiæ magis Cæsari quam Archelao tribuentes. |

At Cæsarea they were met by Sabinus the procurator of Syria, who was on his way to Judæa to take charge of Herod’s estate but was prevented from going further by the arrival of Varus, whom Ptolemy on Archelaus’ behalf had begged to come. So for the time being Sabinus, in deference to Varus’ wishes, neither hastened to the citadels nor locked Archelaus out of his father’s treauries, but promised to postpone any action until Cæsar had reached a decision, and remained at Cæsarea. But as soon as restraint was removed by the return of Varus to Antioch and the departure of Archelaus for Rome, he promptly set out for Jerusalem, where he took possession of the Palace and, sending for the garrison commanders and comptrollers, tried to sort out the property accounts and to take possession of the citadels. However, the officers were loyal to Archelaus’ instructions and continued to guard everything in the name of Cæsar rather than of Archelaus. |

| 3 |

| Ad hoc autem Antipas quoque de regno certabat, posteriore superius Herodis testamentum firmius esse defendens, in quo rex ipse Antipas fuerat scriptus : eique se tam Salome quam multi alii cognati qui cum Archelao navigarant suffragio fore promiserant. Ducebat autem secum matrem, fratremque Nicolai Ptolemæum, in quo pro fide apud Herodem probata, nonnihil videbatur esse momenti. Namque illi fuerat amicorum carissimus. Oratori autem Irenæo propter dicendi acrimoniam plurimum confidebat. Unde etiam qui se monuerant ut Archelao pro ætatis merito et secundi testamenti voluntate cederet, audiendos esse non censuit. Romæ vero migraverunt ad eum cunctorum studia propinquorum quibus invisus erat Archelaus, quique præcipue liberi omnes suique juris esse cupiebant, et aut Romano magistratu administrari, aut si hoc non impetrarent, Antipam regem habere. |

Meanwhile Antipas also was strenuously laying claim to the kingdom, insisting that Herod’s earlier will, not the later one, was valid, and that this named him king. He had a promise of support from Salome and many of the relatives who were sailing with Archelaus. He tried also to win over his mother and Nicolaus’ brother Ptolemy, who seemed a weighty supporter in view of the trust Herod had reposed in him; for he had been the most honored of Herod’s Associates. But he placed most confidence in the keen eloquence of Irenæus the orator; he therefore disregarded those who advised him to give way to Archelaus as the elder brother, named in the later will. In Rome all the relatives, who detesed Archelaus, transferred their allegiance to Antipas. They all wanted to be free and autonomous, and either to be governed under a Roman protectorate or, if they could not get that, to have the king be Antipas. |

| 4 |

| Ad hoc etiam Sabini ope nitebatur Antipas, qui Archelaum per epistolas accusaverat apud Cæsarem, Antipam vero multum laudaverat. Itaque digesta crimina Salome et ceteri qui cum ea sentirent, Cæsari tradiderunt, et post eos Archelaus gestorum suorum perscripta capitula, patrisque anulum per Ptolemæum, rationesque administrationis intromisit ad Cæsarem. Ille autem secum præmeditans ea quæ ab utraque parte dicerentur, ubi et regni magnitudinem, multitudinemque redituum animadvertit, atque insuper Herodis familiam numerosam, perlectis etiam Vari ac Sabini litteris, optimates Romanorum ad concilium vocat, in quo tunc primum ex Agrippa ac filia sua natum Gajum sedere jussit, filium adoptivum : atque ita partibus prosequendi copiam dedit. |

In these endeavors Antipas was aided by Sabinus, who sent letters denouncing Archelaus to Cæsar and lavishing praise on Antipas. Salome and her friends arranged all the charges and put the file in Cæsar’s hands. Then Archelaus in his turn sent Ptolemy with a written summary of his own claims, his father’s ring, and the official records. Cæsar, having considered in private the rival dossiers, the size of the kingdom, the value of the revenue, and also the number of Herod’s children, read the dispatches from Varus and Sabinus about the matter. Then he summoned a council of Roman officials, giving a seat on it for the first time to Gajus — son of Agrippa and his own daughter Julia, and adopted by him — and invited the disputants to put their case. |

| 5 |

| Igitur Salomes filius Antipater (namque is erat orator acerrimus eorum qui adversabantur Archelao) accusationem proposuit, insimulans Archelaum, quasi verbis quidem de regno videretur contendere, re autem vera jamdudum rex esset effectus, et apud aures modo Cæsaris cavillaretur quem judicem successionis expectare noluisset. Nam post Herodis mortem, quibusdam ut diadema sibi imponerent subornatis, regis eum more in solio aureo residentem, partim ordines militiæ permutasse, partim condonasse promotiones ; et insuper his omnia annuisse populo, quæ velut a rege impetranda petiisset : maximorumque reos criminum quos pater suus vinxerat, absolvisse : qui quum ista fecisset, modo regni umbram a Domino postulaturus venisset, cujus sibi corpus ipse rapuisset, ut non rerum, sed vocabulorum dominum esse Cæsarem demonstraret. Ad hæc ei, quod etiam luctum patris assimulasset, objiciebat. Quum interdiu quidem personam componeret in mærorem, noctu vero ad comissationes usque potaret. Denique seditionem vulgi ex hac indignatione conflatam esse dicebat. Totius enim orationis suæ vires, eorum multitudine qui circa Templum cæsi fuerant astruebat. Hos enim ad diem festum quidem venisse ; ad hostias vero quas ipsi mactandas venerant, crudeliter esse jugulatos : tantumque in Templo funerum esse congestum, quantum nullum ab externis illatum bellum implacabile congessisset. Itaque hujus crudelitatis Herode præscio, ne spe quidem regni unquam eum dignum esse visum nisi quum sanæ mentis inops erat, animo deterius ægrotante quam corpore, et quem in secundo testamento successorem scriberet, ignorabat : præsertim, qui priore testamento successorem scriptum incusare nihil posset quod, incolumi corpore omnique vitio purgata mente, fecisset. Ut tamen quis firmius esse ponat morbo laborantis arbitrium, ipsum se Archelaum abdicasse regia dignitate, multis in eam contra leges admissis. ¿ Nam qualem fore si acciperet a Cæsare principatum qui, antequam acciperet, tantum populum peremisset ? |

Salome’s son Antipater at once rose. The sharpest speaker among Archelaus’ opponents, he pointed out that, though professedly Archelaus was only laying claim to the throne, actually he had been reigning for a long time, so that it was mockery now to have an audience with Cæsar, whose decision on the succession he had not waited for. As soon as Herod was dead he had secretly bribed certain persons to crown him; he had sat is state on the throne and given audience as a king; he had altered the organization of the army and granted promotions. Furthermore, he had conceded to the people everything for which they had petitioned him as though a king, and had released men whom his father had imprisoned for shocking crimes. And now he had come to ask his master for the shadow of that kingship of which he had himself snatched the substance, allowing Cæsar control not of realities but of names. Antipater also alleged that his mourning for his father was a sham — that in the daytime he assumed a mask of grief and at night indulged in drunken orgies, which had aroused indignation and caused popular unrest. The speaker directed the whole force of his argument to the number of people killed around the Sanctuary, who had come to the Feast only to be brutally murdered alongside their own sacrifices — such a huge heap of corpses in the Temple courts as one would scarcely have expected to see if a savage invasion by foreigners had piled it up. Recognizing this vein of cruelty in his son, Herod had never given him the least hope of succeeding to the throne till his mind became more decayed than his body, and he was incapable of logical thought and did not realize what sort of man he was making his heir by his new will, though he had no fault to find with the heir in the earlier one, written when his health was good and his mind quite unimpaired. As far as anyone making more valid the decision of a man suffering from a sickness is concerned, Archelaus had himself abdicated the dignity of kingship due to the many illegalities he had perpetrated against it; what would he be like after receiving authority from Cæsar, when he had put so many to death before receiving it? |

| 6 |

| Multa in hunc modum prosecutus Antipater, multis ex numero circumstantium propinquorum in singula crimina testibus exhibitis peroravit. Surrexit autem Nicolaus defensor Archelai, et ante omnia cædem in Templo necessario factam esse perdocuit ; nam quorum necis argueretur, non regni solum, sed etiam ipsius judicis — id est, Cæsaris — hostes fuisse : aliorum autem criminum suasores adversarios ipsos demonstravit. Secundum vero testamentum idcirco ratum manere postulabat, quod Herodes in eo successoris sui firmatorem Cæsarem constituisset. Nam qui tantum saperet, ut rerum Domino potestate sua cederet, nec unquam in heredis errasse judicio, sed sano corde quem constitueret elegisse, qui per quem constitui deberet non ignoravit. |

After continuing in this veign at considerable length and bringing forward most of the relatives to witness the truth of each accusation, Antipater sat down. Then Nicolas rose to defend Archelaus and argued that the slaughter in the Temple was unavoidable, for those killed had been enemies not only of the crown but of Cæsar who was now awarding it. The other measures with which he was charged had been taken on the advice of the accusers themselves! As for the later will, he claimed that it was proved valid primarily by the fact that in it Cæsar was appointed executor; a man sensible enough to put the management of his affairs into the hands of the supreme ruler would never make an error in the choice of an heir; the man to be designated heir was chosen with a sane mind by a man who was not unaware of him through whom that heir had to be designated. |

| 7 |

| Quum autem omnibus expositis, etiam Nicolaus perorasset, in medium progressus Archelaus, ad genua Cæsaris accidit ocius. Quo perbenigne Cæsar erecto, quod paterna quidem successione dignus esset, ostendit ; certum vero nihil pronuntiavit. Sed illo die dimisso concilio, secum ipse de cognitis deliberabat, utrum ex his qui testamento continerentur, aliquem regni oporteret constitui successorem, an toti familiæ distribui principatum. Multitudo enim personarum egere subsidio videbatur. |

When Nicolas too had had his say, Archelaus came forward and quickly fell down at Cæsar’s knees. The emperor raised him up in the most gracious manner and declared that he deserved to succeed his father, but made no definite announcement. After dismissing those who had formed his council that day, he thought over in private what he had been told, considering whether to appoint one of those named in the wills to succeed Herod, or to divide the power among the whole family; for a large number of individuals seemed to be in need of help. |

|

| ⇑ § III |

Judæos inter et Sabinianos

pugna acris,

et magna strages Hierosolymis. | The Jews fight a great battle with Sabinus’s soldiers, and a great destruction is made at Jerusalem. |

| 1 |

— Caput B-2 —

De pugna et strage Hierosolymis inter Judæos et Sabinianos |

| Sed antequam de his quicquam statueretur a Cæsare, mater Archelai Malthace, morbo correpta, moritur. Et variæ litteræ de Syria perlatæ sunt, Judæos defecisse nuntiantes : quod Varus fore prospiciens in Hierosolymam, postquam Archelaus navigarat, ascendit, ut incentores seditionis prohiberet. Et quia multitudo cessatura non videbatur, ex tribus quas ex Syria duxerat secum legionibus, unam in Civitate reliquit : atque ita in Antiochiam ipse remeavit. At Sabinus, quum postea in Hierosolymam venisset, causas novarum rerum Judæis præbuit : modo vim custodibus, ut sibi arces traderent, adhibendo, nunc maligne regis exquirendo pecunias. Non autem solis relictis a Varo militibus fretus erat, sed etiam servorum suorum multitudine, quos etiam omnes armatos avaritiæ ministros habebat. Festo autem quinquagesimo die, quæ « Pentecoste » a Judæis vocatur, septies septem diebus exactis rediens, ex eorum numero vocabulum nacta, non religionis sollemnitas populum, sed indignatio congregavit. Denique concursus infinitæ multitudinis ex Galilæa, itemque Idumæa et Hierichunte, transque Jordanem positis regionibus, factus est : quum indigena ex ipsa Civitate populus Judæorum, et numero simul et alacritate præstaret : et tripartita manu terna castra collocaverunt, una in Septentrionali regione Templi, altera in meridionali, Hippodromum versus, tertiaque in occiduo prope regiam tractu, circumsessosque Romanos undique obsidebant. |

Before Cæsar could reach a decision, Archelaus’ mother Malthace died of an illness, and a number of letters arrived from Varus in Syria reporting that the Jews had defected. He had seen this coming, and so when Archelaus has sailed, he had gone to Jerusalem to restrain the inciters, as it was obvious that the populace would not remain quiet. Then, leaving in the City one of the three legions he had brought from Syria, he returned to Antioch. However, when Sabinus arrived in Jerusalem afterwards, he gave the people an excuse for rebellion. He used force to get the garrison to hand over the forts and made a ruthless search for the king’s money, employing not only the soldiers left by Varus but a gang of his own slaves, arming them all and using them as instruments of his avarice. On the feast of the fiftieth day, called “Pentecost” by the Jews — which takes place after seven times seven days {(after the Passover)}, taking its name from their number) — the people assembled, not to conduct the usual rites but to vent their wrath. An enormous crowd gathered from Galilee and Idumæa, from Jericho and the regions across the Jordan; while the indigenous Jewish population from the City itself surpassed them in number and enthusiasm. The whole mass split up into three divisions which established themselves in separate camps, one to the north of the Temple, one to the south facing the Hippodrome, and the third near the Palace to the west. Thus they surrounded the Romans and began to blockade them. |

| 2 |

| Sabinus autem multitudine pariter eorumque spiritu perterritus, crebris quidem Varum nuntiis precabatur, ut quam mature ferret auxilium, quasi occasione delenda legione, si quid moræ intervenisset. Ipse vero in altissimam castelli turrim, quæ Phasaëlus vocabatur, evadit, fratris Herodis cognominem, quem Parthi necaverunt. Hinc legionariis, ut in hostes irruerent, signum dabat. Nam præ timore nec ad eos quibus ipse præerat, descendere audebat. Ejus autem præcepto milites obœdientes, in Templum volant, vehementique cum Judæis pugna confligunt : in qua dum nemo desuper adjuvaret, imperitos belli peritia superabant. Postea vero quam multi Judæi porticibus occupatis, a vertice telis eos appetebant, plurimi conterebantur : et neque ex alto jaculantes ulcisci facile poterant, neque comminus dimicantes ferebant. |

Both their numbers and determination alarmed Sabinus, who sent a stream of messengers to Varus to request assistance as soon as possible: if it was delayed, the legion would be cut to pieces. He himself went up to the highest tower of the fortress, the one called Phasaël after Herod’s brother who had died at the hands of the Parthians. From there he signalled to the legionaries to attack the enemy, for he was too panic-stricken even to go down to his own men. Doing as they were told, the soldiers dashed into the Temple and engaged in a fierce combat with the Jews, in which, as long as no one shot at them from above, their experience of war gave them the advantage. But when many of the Jews climbed on to the top of the colonnades and attacked them with missiles from above, casualties were heavy, and they could neither easily get even with those attacking from above nor resist those who fought them hand to hand. |

| 3 |

| Ab utrisque tamen afflicti, succendunt porticus, opere magnitudine atque ornatu mirabiles. Ibique tum multi flamma subito comprehensi aut ea consumebantur, aut in hostes desilientes ab ipsis occidebantur ; alii retrorsum cedentes præcipitabantur ex muro ; nonnulli, desperata salute, incendii periculum suis gladiis præveniebant. Qui tamen ex mœnibus obrependo in Romanos fecissent impetum, metu attoniti nullo negotio subigebantur, donec omnibus, aut interemptis aut timore disjectis, thesauro Dei defensoribus destituto manus milites attulerunt, et XL• ex eo talenta diripuere ; quorum quæ furto sublata non sunt, conquisivit Sabinus. |

Hard pressed from both directions, the soldiers set fire to the colonnades, works remarkable for both size and magnificence. The men on top were suddenly hemmed in by the flames: many of them were burnt to death; many others jumped down among the enemy and were destroyed by them; some turned about and flung themselves from the wall; a few, seeing no way of escape, fell on their own swords and forestalled the flames; a number who crept down from the walls and, frenzied with terror, made an attack on the Romans were overpowered without trouble. After they had all been either killed or dispersed in fear, the soldiers got their hands on the unguarded treasury of God and carried off forty talents; what they did not steal Sabinus gathered up. |

| 4 |

| At Judæos multo plures, magisque pugnaces, tam virorum quam opum interitus in Romanos contraxit. Obsessaque his regia, minitabuntur exitium, nisi quam primum inde secederent — Sabino, si vellet, una cum legione abeundi copiam pollicentes. Quibus opitulabantur regiorum plurimi qui ad eos sponte transfugerant. Pars tamen bellicosior erat, Sebastenorum tria milia, hisque Rufus et Gratus præpositi, unus peditum rector, at vero equitum Rufus : quorum uterque vi corporis atque prudentia, etiam si nullam manum obœdientem haberent, magnum tamen momentum belli Romanis addidissent. Itaque Judæi quidem instare obsidioni, simul et castelli mœnia temptantes, et ad Sabinum clamantes ut discederet neu impediret habituros tanto post tempore patriam libertatem. Sabinus autem, quamvis optaret evadere, fidem tamen pollicitationibus non habebat : sed eorum lenitatem, insidiarum esse illecebram suspicabatur : simulque auxilium Vari sperans, obsidionis periculum perferebat. |

But the loss of men and property attracted many more Jews, and more bellicose ones, to oppose the Romans. They surrounded the Palace and threatened to destroy all its occupants unless they withdrew forthwith, but promised safe conduct to Sabinus if he was prepared to take his legion away. They were reinforced by the bulk of the royal troops, who had deserted to them. But the most warlike section, 3,000 men from Sebaste with their officers, Rufus and Gratus, attached themselves to the Romans. Gratus commanded the royal infantry, Rufus the cavalry; each of them, even without the men under him, with his physical strength and mental ability, would have provided the Romans with the dominant warfighting power. The Jews conducted a vigorous siege, assaulting the walls of the fortress and at the same time vociferously urging Sabinus and his soldiers to withdraw and not to keep the Jews from at long last recovering their ancestral independence. Sabinus would have been only too glad to withdraw quietly, but he distrusted their promises and suspected that their soft words were a bait to catch him. As he was also expecting Varus’ reinforcements, he continued to hold out. |

|

| ⇑ § IV |

Tumultuantur Herodis veterani.

Judæ latronia.

Simon et Athrongæus

regium nomen invadunt. | Herod’s veteran soldiers become tumultuous. The robberies of Judas. Simon and Athrongæus take the name of king upon them. |

| 1 |

| Eodem tempore per Judæam plurimis locis tumultus erat, multosque ad regni cupidinem tempus impulerat. Nam in Idumæa quidem duo milia veteranorum, qui sub Herode militaverant, congregati, armisque instructi cum regiis decertabant : quibus Achiabus, regis consobrinus, ex vicis munitissimis repugnabat, campestre prœlium declinando. In Sepphori autem Galilææ, Judas, filius Ezechiæ latronum principis, ab Herode quondam rege capti, qui tunc illas regiones vastaverat, non parva multitudine collecta, ruptisque regiis armamentariis, et omnibus quos circa se habebat armatis, contra potentiæ cupidos manus movebat. |

Meanwhile in the country districts also there were widespread disturbances and many seized the opportunity to go after the throne. In Idumæa 2,000 of Herod’s veterans reassembled with their arms and proceeded to fight the royal troops. They were opposed by Achiab, a cousin of the late king; he sheltered behind the strongest fortifications and would not risk a battle in the open. At Sepphoris in Galilee Judas, son of Hezekiah — a bandit chief who once overran the country and had been captured by King Herod — collected a considerable force, broke into the royal amory, equipped his followers, and attacked the other seekers after power. |

| 2 |

| Trans flumen quoque Simon quidam ex regiis servis pulchritudine simul et vastitate corporis fretus, imposito sibi diademate, cum latronibus quos congregaverat ipse circumiens, et apud Hierichunta regiam et multa alia magnifica deversoria igni corrupit, facilem sibi prædam ex incendio comparans. Omnesque habitationes, quibus aliquid decoris erat, concremasset, nisi Gratus, regiorum peditum rector, ex Trachone sagittarios itemque Sebastenorum pugnacissimos ducens, properasset occurrere. Ubi peditum quidem in pugna multi consumpti sunt ; ipse autem Simonem compendio prævenit, ardua valle fugientem, et ex transverso percussum in cervice dejecit. Incensæ sunt autem et quæcunque Jordani proximæ fuerunt sedes regiæ, apud Betharantes, quorundam aliorum manu conflata ex locis ulterioribus. |

On the other side of the Jordan, Simon, one of the royal slaves, considered that his good looks and great stature entitled him to set a crown on his own head. Then he went around with a band of robbers and burnt down the palace at Jericho and many magnificent lodgings, securing easy plunder for himself out of the flames. He would have reduced every elegant building to ashes had not Gratus, commander of the royal infantry, taken the archers from Trachonitis and the most battle-hardened troops from Sebaste and rushed to confront him. At that point many of his foot soldiers were killed; Gratus himself headed off Simon, who was fleeing via a steep ravine and, hitting him sideways in the neck, laid him low. But whatever palaces were near the Jordan at Beth Haram were burnt down by another gang from further out. |

| 3 |

| Tunc enim pastor quidam, cui nomen Athrongæus, regnum affectare ausus est ; quod ut speraret, vi corporis animæque fiducia mortem contemnentis impulsus est, ac præterea fratrum quattuor sibi similium robore, quorum singulis tanquam ducibus et satrapis attributa manu armatorum, ad incursus utebatur. Ipse autem veluti rex majora negotia procurabat. Et tum quidem etiam diadema sibi imposuit. Non parvo autem post tempore, cum fratribus suis vastando territoria, et occidendo præcipue Romanos, itemque regios perseveravit : quum nec Judæorum quisquam effugeret, qui lucrum aliquod ferens venisset in manus. Ausi sunt etiam apud Ammauntem repertum Romanorum agmen circumvenire, qui frumenta legioni atque arma portabant. Ubi Arium quidem centurionem et quadraginta fortissimos jaculis confecere : ceteri vero in eodem periculo constituti, auxilio Grati, qui cum Sebastenis advenit, elapsi sunt. Multis in hunc modum contra indigenas, itemque alienigenas per omne bellum gestis, post aliquod tempus tres ex his comprehensi sunt — natu quidem maximus ab Archelao, duo vero, qui ætate sequebantur, in manus Grati ac Ptolemæi delati. Nam quartus Archelao pactione concessit. Sed hic finis eos postea secutus est. Tunc autem latrocinali bello cunctam inflammabant Judæam. |

Then a certain shepherd by the name of Athrongæus dared to make a grab for the throne. His hopes were based on his physical strength and contempt of death, and on the support of four brothers like himself. Each of these he put in charge of an armed band, employing them as generals and satraps on his raids, and reserving to himself as king the settlement of major problems. He set a crown on his own head, but continued for a considerable time to raid the country with his brothers. Their principal purpose was to kill Romans and the royal troops; but not even a Jew could escape if he fell into their hands with anything valuable on him. Once they ventured to surround an entire century of Romans near Emmaus, when they were conveying food and munitions to their legion. Hurling their spears, they killed the centurion Arius and forty of his best men; the rest were in danger of meeting the same fate until the arrival of Gratus with the troops from Sebaste enabled them to escape. Such was the treatment that they meted out to natives and foreigners alike throughout the war; but after a while three of them were defeated, the eldest by Archelaus, the next two in age in an encounter with Gratus and Ptolemy; the fourth submitted to Archelaus on terms. It was, of course, later that their career came thus to an end: at the time we are describing they were harassing all Judæa with their brigandage. |

|

| ⇑ § V |

Judæorum motus

a Qunitilio Varo compositi :

seditiosi quasi

bis mille crucifixi. | Varus composes the tumults in Judæa and crucifies about two thousand of the seditious. |

| 1 |

— Caput B-3 —

De Vari gestis circa Judæos crucifixos. |

| Varus autem, acceptis Sabini et principum litteris, toti legioni metuens, opem his ferre properabat. Itaque cum duabus reliquis legionibus et quattuor alis equitum in Ptolemaida profectus, eodem regum atque optimatum auxilia convenire jussit. Ad hæc a Berytiis etiam, quum per eorum transiret oppidum, mille et quingentos accepit armatos. Ubi vero in Ptolemaidem tam cetera manus auxiliorum, quam propter Herodis inimicitias Aretas rex Arabum non cum exiguo numero equitum peditumque pervenit, statim exercitus partem in Galilæam (quæ Ptolemaidi propinqua erat) dirigit, amici sui Galli filio his rectore præposito. Qui mox et adversus quos ierat omnes in fugam vertit et, Sepphori civitate capta, ipsam quidem incendit, incolas vero ejus servitio subjugavit. Varus autem ipse cum omni exercitu Samaria potitus, civitate quidem abstinuit, quod inter aliorum turbas nihil eam movisse deprehendit ; castris autem ad vicum positis qui appellatur Arun, Ptolemæi possessionem propterea direptam ab Arabibus qui et amicis Herodis infensi erant, inde ad Sappho progreditur, alterum vicum tutissimum, quem similiter, omnesque reditus ibi repertos depopulati sunt. Cædis autem ignisque plena erant omnia, nec prædationi Arabum quicquam obstabat. Exusta est et Ammaus jussu Vari, necem Arii ceterorumque indigne ferentis, habitatoribus ejus fuga dispersis. |

When Varus received the dispatches of Sabinus and the officers, he was naturally afraid for the whole legion and hurried to the rescue. He picked up the other two legions and the four troops of horse attached to them and marched to Ptolemais, giving instructions that the auxiliaries provided by kings and local potentates should meet him there. In addition he collected 1,500 heavy infantry as he passed through the city of Berytus. At Ptolemais he was joined by a great number of allies. Prominent among these was Aretas the Arab, who because he had hated Herod brought a considerable force of infantry and cavalry. Varus at once dispatched a portion of his army to the part of Galilee near Ptolemais, under the command of {Gajus,} the son of his friend Gallus. Gajus soon both routed those who blocked his way, and captured the city of Sepphoris and burnt it, enslaving the inhabitants. With the rest of his forces Varus himself marched into Samaria, but kept his hands off the city {(of Sebaste)} as he learned that, when the whole country was in a ferment, there had been complete quiet there. He encamped near a village called Arus, which belonged to Ptolemy and for that reason had been plundered by the Arabs, who hated Herod’s friends as well. From there he went on to Sappho, another fortified village, which they plundered in the same way, seizing all the revenues they found there. Fire and bloodshed were on every side, and nothing could check the depredations of the Arabs. Emmaus too, abandoned by its inhabitants, was destroyed by fire at the command of Varus to avenge Arius and those who had perished with him. |

| 2 |

| Hinc progressus ad Hierosolymam cum exercitu, solo visu Judæorum castra disjecit, et alii quidem per agros abiere fugientes ; qui vero intra Civitatem degebant, suscepto eo, seditionis causas in alios conferebant, nihil quidem se penitus movisse dicentes, sed propter diem festum receptam necessario multitudinem, in Civitate obsessos esse potius cum Romanis quam cum dissidentibus conspirasse. Ante vero obviam ei venerant Josephus, Archelai consobrinus, et cum Grato Rufus, ducentes exercitum regium, et Sebastenos, et Romanos milites ornatos habitu consueto. Sabinus enim nec in os Vari venire ausus, jamdudum ex Civitate ad mare discesserat. Varus autem dispertitum adversus auctores tumultus per agros dimisit exercitum ; multisque sibi exhibitis quos minus turbulentos invenisset, custodiæ tradidit, maxime vero nocentium prope ad duo milia cruci suffixit. |

Then Varus marched on to Jerusalem, where at the first sight of him the Jewish camp dispersed, the fugitives disappearing into the countryside. The citizens, however, welcomed him and shifted all responsibility for the revolt to others, declaring that they had not lifted a finger but had been forced by the occurrence of the Feast to receive the swarm of visitors, so that far from joining in the attack they had, like the Romans, been besieged. Before this he had been met by Joseph, the cousin of Archelaus, by Rufus and Gratus at the head of the men from Sebaste as well as the royal army, and by the members of the Roman legion with the normal arms and equipment — for Sabinus, not daring to come into Varus’ sight, had already left the City for the sea. Varus sent portions of his army about the countryside in pursuit of those responsible for the upheaval, and great numbers were brought in: those who seemed to have taken a less active part he kept in custody, while the ringleaders were crucified — about two thousand. |

| 3 |

| Adhuc autem circa Idumæam superesse decem armatorum milia nuntiato, confestim Arabas domum abire jubet ; quod eos non auxiliantium more uti militia, sed pro sua libidine, et supra quam ipse vellet, agros vastare perspexit : suis autem comitatus agminibus, in adversarios properabat. Verum illi se Varo, priusquam in manus veniretur, Achiabi consilio tradiderunt. Varus autem multitudini, venia data, duces ejus interrogandos misit ad Cæsarem. At ille quum ignovisset ceteris, in nonnullos regis cognatos (erant enim quidam inter eos Herodis propinqui) animadvertit, quod omnino contra regem suum arma cepissent. Varus autem hoc modo rebus apud Hierosolymam compositis, eademque legione quæ dudum in præsidio Civitatis fuerat, ibi relicta, Antiochiam rediit. |

Information reached him that in Idumæa there still remained a concentration of 10,000 men, heavily armed, so he immediately ordered the Arabs to leave, because he found that they were not behaving militarily as allies but ravaging the countryside as they wished and beyond what he himself wanted. With his own legions he then hurried to meet the rebels. But before it came to battle, they took the advice of Achiab and surrendered to Varus. Varus acquitted the rank and file of any responsibility, but sent the leaders to Cæsar to be examined. Cæsar pardoned most of them, but some of the king’s relatives — a few of the prisoners being connected with Herod by birth — he sentenced to death for having fought against a king of their own blood. Varus, having thus settled matters in Jerusalem, left as garrison the same legion as before and returned to Antioch. |

|

| ⇑ § VI |

Multa Archelao objiciunt Judæi,

et Romanorum prætoribus

subjici postulant.

Quibus auditis,

Cæsar liberis Herodis

paternas possessiones

pro arbitrio suo distribuit.

| The Jews greatly complain of Archelaus and desire that they may be made subject to Roman governors. But when Cæsar had heard what they had to say, he distributed Herod’s dominions among his sons according to his own pleasure. |

| 1 |

— Caput B-4 —

De Ethnarcha Judæorum instituto. |

| Romæ autem Archelao alia rursus cum Judæis causa conflata est, qui ante seditionem, permissu Vari, legati exierant, jus genti suæ liberum petituri. Erant autem numero quinquaginta, qui venerant, et astabant eis plus quam octo milia Judæorum Romæ degentium. Itaque convocato a Cæsare optimatum Romanorum amicorumque concilio in Palatini Apollinis templum (quod privatum ipsius erat ædificium admirandis opibus exornatum), multitudo quidem Judæorum constitit cum legatis, contraque Archelaus cum amicis. Cognatorum autem amici

ab utraque parte secreti erant. Nam et cum Archelao stare propter odium atque invidiam recusabant, et cum accusatoribus conspici pudore Cæsaris prohibebantnr. Inter quos erant etiam Philippus, Archelai frater, benevolo animo duabus ex causis præmissus a Varo : ut et Archelao subveniret ; et si regnum Herodis nepotibus ejus distribui placuisset, partem aliquam mereretur. |

At Rome Archelaus was involved in a new dispute with some Jews who before the revolt had been permitted by Varus to come as ambassadors and plead for racial autonomy. These numbered fifty and were backed by more than 8,000 of the Jews in Rome. Cæsar summoned a council of Roman officials and his own friends in the Palatine temple of Apollo which he himself had built and decorated regardless of expense. The Jewish mob stood with the ambassadors facing Archlaus and his friends: the acquaintances of his relatives stood apart from both; for hatred and envy made them unwilling to be associated with Archlaus, while they did not want to be embarrassed in front of Cæsar by being seen with his accusers. They had also the support of Philip, the brother of Archelaus, who had been sent by the kindness of Varus for two purposes — he was to help Archelaus and, if Cæsar divided Herod’s estate among all his descendants, he was to secure a share of it. |

| 2 |

| Jussit autem accusatoribus exponere, quænam contra leges fecisset Herodes. Primum non se regem, sed omnium qui usquam fuissent tyrannorum crudelissimum tolerasse dicebant. Deinde multis ab eo trucidatis, ea pertulisse superstites questi sunt, ut beatiores mortui putarentur. Non enim tormentis solum eum lacerasse corpora subjectorum, sed etiam, gentis suæ civitatibus deformatis, exteras ornavisse, populisque alienis Judææ sanguinem condonasse. Pro antiqua vero felicitate ac patriis legibus, nationem suam tanta egestate simul ab eo atque iniquitate repletam, prorsus ut plures ex Herode paucis annis clades sustinuerint, quam omni ævo majores sui, postquam ex Babylone discessere, perpessi sunt, Xerxe tunc regnante ad discordias concitati. Verum se tamen ad modestiam ex adversæ fortunæ consuetudine profecisse, ut etiam successionem voluntariam acerbissimæ servitutis subirent, qui et Archelaum, tanti tyranni filium, patre mortuo regem appellassent nihil morati, et una cum eo luxissent mortem Herodis, ac pro ejus successore vota celebrassent. Illum autem, quasi metueret ne non certus ejus filius videretur, a cæde trium milium civium regni sumpsisse primordia ; et, quia principatum meruerit, tot immolasse Deo hominum victimas, tot festo die Templum cadaveribus implevisse. Recte igitur eos qui de tantis malis superessent, aliquando respexisse calamitates suas, et belli lege cupere vulneribus excipiendis ora præbere ; atque ab Romanis precari, ut Judææ reliquias misericordia dignas existimarent, neve quod ex ea natione restaret, his objicerent, a quibus crudelissime lacerabatur ; sed patriam suam conjungi Syriæ finibus, ac per judices Romanos administrari decernerent ; hoc enim modo probatum iri, Judæos qui nunc veluti turbulenti ac belli cupidi reprehenduntur, moderatis rectoribus obœdire nosse. Judæorum quidem accusatio ejusmodi petitione conclusa est. Quum autem surrexisset contra Nicolaus, primum criminibus quæ in reges erant proposita dissolutis, nationem cœpit arguere, quia neque gubernari facilis esset naturaque regibus vix pareret. Una etiam propinquos Archelai, qui se ad accusatores contulerant, insimulabat. |

When the accusers were called upon they first went through Herod’s crimes, declaring that it was not to a king that they had submitted but to the most savage tyrant that had ever lived. Vast numbers had been executed by him, and the survivors had suffered so horribly that they envied the dead. He had not only shredded the bodies of his own subjects with torture but also, disfiguring his own people’s cities, adorned foreign ones, and had shed Jewish blood to gratify foreigners. Depriving them of their old prosperity and their ancestral laws, he had reduced his people to poverty and utter lawlessness. In fact, the Jews had endured more calamities at Herod’s hands in a few years than their ancestors had endured in all the time since they left Babylon, provoked to rebellion by the then reigning Xerxes {(actually, Artaxerxes I, 465—424 B.C.)}. But they had become so subservient and inured to misery that they had even voluntarily entered into the continuance of that extremely bitter servitude, and on Herod’s death had immediately called Archelaus, the son of such a tyrant, king. They had joined with him in mourning Herod’s death and in praying for the success of his own reign. But he, as though afraid of not seeming to be a bonafide son of his, had inaugurated his reign by putting 3,000 citizens to death and, because he had earned the principate, offered to God that number of sacrifices for his enthronement, and filling the Temple with that number of dead bodies during a Feast! It was only right that those who had survived such a succession of calamities should have finally reflected on their sufferings and desired according to the law of war to receive their blows face on; they begged the Romans to pity the remnant of the Jews, and not to throw what was left of them to those who would tear them to pieces, but to unite their country with Syria and administer it through Roman officials. This would show that men now accused of anarchy and aggression knew how to submit to reasonable authority. With this request the Jews brought their accusation to an end. Nicolaus then rose and refuted the charges brought against the kings, and began to accuse the nation, because it was not easy to rule and by nature would obey its kings only with difficulty. Lastly, he attacked those of Archelaus’ relatives who had gone over to the accusers. |

| 3 |

| Sed tum quidem partibus Cæsar auditis, conventum diremit. Paucis autem diebus post, mediam regni partem sub ethnarchiæ nomine dedit Archelao ; etiam regem, si se dignum præbuisset, facturum esse pollicitus. Reliquam vero dimidiam in duas tetrarchias divisit, duobusque aliis Herodis filiis attribuit : unam Philippo, alteram Antipæ, qui cum Archelao de regno certaverat. Hujus parti cesserat trans flumen regio, et Galilæa, quarum ducenta talenta reditus erant. Batanea vero et Trachon, et Auranitis, et quædam partes domus Zenonis, circa Jamniam, Philippo destinatæ sint, quæ talentorum centum reditus ministrabant. Archelai vero ethnarchia Idumæam, omnemque Judæam, et Samariam habebat quarta tributorum parte levatam, pro munere quia non rebellasset cum ceteris. Ac civitates quibus imperaret ei traditæ sunt Stratonis Pyrgus, et Sebaste, et Joppe, et Hierosolyma. Ceteras autem, Gazam et Gadaram et Hippon, regno avulsas, Syriæ Cæsar adjecit. Erant autem reditus Archelai quadringenta talenta. Quin et Salomen, præter illa quæ testamento regis ei relicta erant, Jamniæ dominam, et Azoti, et Phasaëlis idem Cæsar constituit, regiamque apud Ascalonem largitus est ; ex quibus omnibus talentorum sexaginta reditus colligebantur. Domum vero ejus ethnarchiæ subdidit Archelai. Quum autem ceteris quoque Herodis propinquis testamento relicta solvisset, duas ejus filias virgines extrinsecus quingentis milibus pecuniæ donavit, easque nuptum Pheroræ filiis collocavit. Diviso autem Herodis patrimonio, etiam sibi relictas ab eo facultates ad mille talenta eis distribuit, exceptis suo nomine quibusdam rebus vilissimis propter honorem defuncti. |

After hearing both sides, Cæsar adjourned the meeting; but a few days later he gave half the kingdom to Archelaus, with the title of ethnarch and the promise that he should be king if he showed that he deserved it: the other half he divided into two tetrarchies which he bestowed on two other sons of Herod, one on Philip, the other on {Herod} Antipas who was disputing the kingship with Archelaus. Under Antipas were placed the trans-Jordan region and Galilee with a revenue of two hundred talents, while Batanea, Trachonitis, Auranitis and some parts of Zenodorus’ domain around Jamnia, with a revenue of a hundred talents, were put under Philip. Archelaus’ ethnarchy comprised Idumæa, all Judæa, and Samaria, which was excused a quarter of its taxes as a reward for not joining in the revolt. The cities placed under his rule were Strato’s Tower, Sebaste, Joppa and Jerusalem; the Greek cities of Gaza, Gadara and Hippos were detached from the kingdom and added to Syria. The revenue from the territory assigned to Archelaus amounted to four hundred talents. Salome, in addition to what the king had left her in his will, was appointed mistress of Jamnia, Azotus and Phasaëlis, and as a gift from Cæsar she received the palace at Ascalon. From all these she collected a revenue of sixty talents; but her domain came under the general control of Archelaus. And after he had also granted to Herod’s other relatives what had been left to them in his will, in addition he gave the two unmarried daughters {(Roxanne and Salome II)} 500,000 drachmas, and arranged for them to marry the sons of Pheroras. After dividing up Herod’s estate, he also shared out among them all the legacy bequeathed to him by Herod — the sum of 1,000 talents — after picking out a few treasures of no intrinsic value in memory of the departed. |

|

|

| ⇑ § VII |

Historia de Pseudoalexandro.

Relegatur Archelaus,

moritur Glaphyra ;

uterque per quietem

præmonitus. | The history of the spurious Alexander. Archelaus is banished and Glaphyra dies, after what was to happen to both of them had been showed them in dreams. |

| 1 |

— Caput B-5 —

De subditicio falsoque Alexandro, eoque deprehenso. |

| Interea quidam juvenis natione Judæus, apud quendam libertinum Romanorum in Sidoniorum oppido educatus, illum se, formæ similitudine, quem Herodes necaverat, Alexandrum esse mentitus, fallendi spe Romam venit. Hujus autem facinoris habebat socium quendam gentilem suum, omnes regni actus optime scientem ; a quo instructus, affirmabat eorum se misericordia, qui sui atque Aristobuli occidendi causa missi fuerant, similibus corporibus subditis, morti esse surreptos. Denique his multos jam Judæos fefellerat in Creta degentes, ac liberaliter illic acceptus, Melumque inde transmissus, ibique ampliore quæstu cumulatus, etiam hospites suos magna verisimilitudine Romam secum navigare pellexerat. Postremo delatus Dicæarchiam, multisque muneribus ab Judæis ejus loci donatus, quasi rex a paternis amicis deducebatur. Ad hoc enim fidei processerat formæ similitudo, ut qui Alexandrum illum viderant, planeque noverant, hunc eum esse jurarent. Igitur omnes etiam Romæ Judæi, visendi ejus studio circumfusi properabant ; et infinita multitudo per vicorum angustias, quocunque ferebatur, conveniebant. Tanta namque dementia multos ceperat, ut illum sella portarent, ac regale obsequium propriis ei sumptibus exhiberent. |

At this period a young man, Jewish by birth but brought up at Sidon by a Roman freedman, took advantage of his physical resemblance to pass himself off as Alexander, the son whom Herod had executed and, in the hope of deceiving everyone, came to Rome. Assisting him was a compatriot who knew all that went on in royal circles, and who instructed him to say that the men detailed to execute him and Aristobulus had been moved by pity to smuggle them away, leaving instead bodies resembling theirs. With this pretence he deceived many of the Jews in Crete and, welcomed lavishly there, sailed thence to Melos and there got yet more money, by his great plausibility conning his hosts even to travelling with him to Rome. Landing finally at Dicæarchia {(i.e., Puteoli)}, he obtained very large contributions from the Jews there and was escorted on his way like a king by his “father’s” friends. So convincing was the physical likeness that men who had seen Alexander and remembered him well swore it was he. The whole Jewish community in Rome poured out to see him, and an enormous crowd gathered in the narrow streets through which he was carried; for so completely had the Melians lost their wits that they carried him in a sedan chair and furnished him with royal splendor at their own expense. |

| 2 |

| Sed Cæsar, Alexandri vultum optime sciens (accusatus enim apud eum fuerat ab Herode), etsi priusquam videret hominem, fallaciam similitudinis adverterat, hilariori tamen animi spei nonnihil indulgendum putavit, et Celadum quendam, qui Alexandrum bene cognosceret, misit, ut ad se adolescentem deduceret. Qui, illo conspecto, statim personæ differentiam conjectura deprehendit. Maxime vero, ubi corporis ejus duritiam, et servilem formam consideravit, intellexit omne commentum. Valde autem commotus est dictorum ejus audacia ; de Aristobulo enim percontantibus, salvum quidem illum esse commemorabat ; consulto vero non adesse, quia apud Cyprum degeret cavendo insidias ; minus enim se circumveniri posse disjunctos. Itaque ab aliis ei separato vitam dixit a Cæsare præmium fore, si tantæ fraudis prodidisset auctorem. Id autem se facturum ille pollicitus, ad Cæsarem sequitur ; et Judæum indicat, qui formæ suæ similitudine abusus esset ad quæstum. Tanta enim dona ex civitatibus eum singulis abstulisse docuit, quanta vivus Alexander non accepisset. Risit his Cæsar ; et falsum quidem Alexandrum, propter habitudinem corporis, remigum numero inseruit, suasorem vero ejus interfici jussit. Meliis autem sumptuum detrimentum pro amentiæ pretio satis esse judicavit. |

Cæsar, well acquainted with Alexander’s features (since he had been accused by Herod before him), realized even before seeing the man that it was a case of impersonation; but he thought it would be best to be a bit indulgent toward these cheerful hopes and sent one Celadus, who remembered Alexander well, with orders to bring the young man to him. As soon as Celadus set eyes on him, he observed the differences in his face and, noticing that his whole body was tougher and more like a slave’s, saw through the whole plot. But he was most indignant at the impudence of the fellow’s story; for when asked about Aristobulus he insisted that he too was alive, but was deliberately absent because he was staying in Cyprus for fear of treachery: apart they were less likely to be ensnared. Celadus took him aside and said, “Cæsar will spare your life in return for the name of the man who persuaded you to tell such monstrous lies.” The youth replied that he would give him the required information and accompanied him into Cæsar’s presence, where he pointed to the Jew who had made use of his likeness to Alexander for profit: he explained that the man had carried off more gifts from every city than Alexander had received in his whole lifetime. Cæsar was highly amused, and in view of his splendid physique sent the pseudo-Alexander to join his galley-slaves, but ordered the man who led him astray to be put to death. The Melians were sufficiently punished for their folly by the loss of their money! |

| 3 |

— Caput B-6 —

De Archelai exilio. |

| Ethnarchia vero suscepta, memor discordiæ superioris Archelaus, non solum Judæis, sed etiam Samariensibus crudeliter abusus est. Nonoque principatus sui anno, legatis contra se ab utrisque ad Cæsarem missis, ipse quidem in exilium pellitur Viennam, Galliæ civitatem ; patrimonium vero ejus fisco Cæsaris adjudicatur ; quem quidem priusquam evocaretur ad Cæsarem, hujuscemodi somnium vidisse commemorant : novem spicas plenas et maximas a bobus comedi somniaverat ; accitos deinde vates, Chaldæorumque nonnullos quidnam illo putarent indicari somnio, consuluerat. Aliis autem aliter interpretantibus, Simon quidam, Essenus genere, dixerat spicas annos arbitrari, bovesque rerum mutationes, eo quod agros arando verterent ac mutarent. Ideoque regnaturum quidem illum esse tot annos quot significasset numerus aristarum ; varias autem rerum mutationes expertum, esse moriturum. Hisque auditis, Archelaus quinque diebus post ad causam dicendam est evocatus. |

Once established as ethnarch, Archelaus, remembering his previous enmities, treated not only Jews but even Samaritans brutally. In the ninth year of his rule, both peoples sent embassies to accuse him before Cæsar, with the result that he was banished to Vienne in Gaul, and his property transferred to Cæsar’s treasury. Before he was summoned by Cæsar, so we are told, he dreamt that he saw nine large, full ears of wheat devoured by oxen. He sent for the seers and some of the Chaldeans and asked what they thought this foretold. While various interpretations were given, Simon, one of the Essenes, suggested that the ears denoted years and the oxen a political upheaval, because by ploughing they turned the soil over and changed it. Archelaus would rule one year for every ear, and would die after undergoing various upheavals. Five days after hearing this, the dreamer was called to his trial. |

| 4 |

| Dignum autem memoria duxi etiam conjugis ejus Glaphyræ somnium, Archelai filiæ Cappadocum regis, referre : quam quum Alexander prius habuisset uxorem, frater hujus de quo loquimur, Herodis filius regis a quo ille interfectus est, sicut jam designavimus, post illius mortem Jubæ regi Libyæ nuptam, eoque defuncto domum reversam, domique apud patrem in viduitate degentem, Ethnarches Archelaus ubi conspexit ad hoc amoris accensus est, ut eam statim, repudiata conjuge sua Mariamme, sibi copularet. Hæc igitur brevi tempore postquam in Judæam rediit, videre visa est superstantem sibi Alexandrum dicere. « Satis fuerat tibi Libycum matrimonium ; sed tu illo non contenta, rursus ad meos penates reverteris, avidissima viri tertii, et quod gravius est, mei fratris juncta matrimonio. Equidem non dissimulabo contumeliam, teque licet invitam recuperabo. » Atque hoc exposito somnio, vix biduum supervixit. |

I think I might also mention the dream of his wife Glaphyra, daughter of Archelaus, king of Cappadocia. She had first married Alexander, the brother of Archelaus about whom I have been writing, and son of King Herod, who put him to death as already explained. When he died she married Juba, king of Libya, and when he too died, she returned home and lived as a widow in her father’s house until the ethnarch Archelaus saw her and fell so deeply in love with her that he instantly divorced his wife Mariamme and married her. Shortly after her arrival in Judæa she dreamt that Alexander stood over her and said, “Your Libyan marriage was quite enough; but you were not satisfied with it; you came back again to my home after choosing a third husband and, what is worse, my own brother at that! I shall not overlook the insult; I will fetch you back to me whether you like it or not.” She related this dream and lived only two days longer. |

|

| ⇑ § VIII |

Archelai ethnarchia

in provinciam redacta.

Seditio Judæ Galilæi.

Judæorum tres sectæ. | Archelaus’s ethnarchy is reduced into a [Roman] province. The sedition of Judas of Galilee. The three sects of the Jews. |

| 1 |

— Caput B-7 —

De Simone Galilæo. De tribus sectis apud Judæos. |

| Igitur Archelai finibus in provinciam redactis, procurator Coponius quidam. eques Romanus, missus est, ea sibi a Cæsare potestate mandata. Hoc disceptante, Galilæus quidam, Simon nomine, defectionis arguebatur, quia indigenas increparet, si tributum Romanis pendĕre paterentur, dominosque post Deum ferre mortales. Erat autem propriæ sectæ sophista, nulla in re similis aliis. |

The territory of Archelaus was brought under direct Roman rule, and a man of equestrian rank at Rome, Coponius, was sent as procurator with that authority from Cæsar. A Galilean named Simon who disagreed with this was accused of treason because he rebuked the natives if they submitted to paying taxes to the Romans, and after serving God alone accepted human masters. This man was a rabbi with a sect of his own, and was quite unlike the others. |

| 2 |

| Etenim tria sunt apud Judæos genera philosophiæ. Horum unum Pharisæi profitentur, alterum Sadducæi. Tertium vero quod etiam probabilius habetur, Esseni colunt, gente quidem Judæi, verum inter se mutuo amore conjunctissimi ; et qui, præter ceteros, voluptates quidem quasi maleficia vitarent, continentiam vero servare, neque cupiditati succumbere, virtutem maximam ducerent. Itaque nuptias quidem fastidiunt, alienos vero filios, dum adhuc molles sunt, eruditioni traditos pro cognatis habentes, suis moribus diligenter instituunt, non quia conjugia vel humani generis successionem censeant perimendam, sed quia cavendam putent intemperantiam feminarum, nullam earum uni viro fidem servare credentes. |

Among the Jews there are three schools of religious ideology. Of these, one is professed by the Pharisees and the second, by the Sadducees. But the third, seemingly the most commendable, is followed by the Essenes {(< Aramaic hassaya “the Pious ”)}. They are Jews by birth and are strongly attached to each other. Going further than the others, they eschew pleasure-seeking as a vice and regard remaining celibate and not giving in to lust as the highest virtue. Scorning wedlock, they select other men’s children while still pliable and, considering those handed over to them for education as their relatives, diligently fashion them after their own pattern — not that they wish to do away with marriage as a means of continuing the race, but they are afraid of the promiscuity of women and convinced that none of the sex remains faithful to one man. |

| 3 |

| Quin et divitiarum contemptores sunt, rerumque apud eos communicatio admirationi habetur, neque invenias alteri alterum opulentia præstare ; legemque sibi dixerunt ut, qui disciplinam suam sectari vellent, bona contubernio publicarent. Ita enim fore, ne vel paupertatis humilitas vel divitiaram dignitas appareret sed, permixtis facultatibus, velut inter fratres unum esset omnium patrimonium. Probro autem ducunt oleum, et si quis vel invitus unctus fuerit, munditiis corpus absterget ; quoniam squalorem decorem putant, dummodo semper in veste sint candida. Designatos autem communium rerum procuratores habent, et ad usus omnium singulos indivisos. |

They are contemptuous of wealth: the way they share things among themselve has to be admired, and none of them will be found to be better off than the rest: their rule is that novices admitted to the sect must surrender their property to the order, so that among them all neither humiliating poverty nor excessive wealth is ever seen, but each man’s possessions go into the pool and as with brothers their entire property belongs to them all. Oil they regard as polluting, and if a man is unintentionally smeared with it he wipes himself clean; for they consider unsmoothness proper, while they always wear white. For the common property they have designated managers, and for the benefit of all, each individual without distinction. |

| 4 |

| Non est autem illis una civitas certa, sed in singulas multi domicilia transferunt, et aliunde advenientibus sectæ suæ professoribus, quicquid habeant, promptum exhibent quasi proprium. Denique tanquam consuetissimi ad eos ingrediuntur, quos nunquam ante viderunt. Hinc est quod cum peregrinantur, propter latrocinia tantum armentur, neque præterea quicquam ferant. In singulis autem civitatibus, ex eodem collegio specialis curator hospitum constituitur qui eorum vestimenta ceteraque usui necessaria tueatur. Amictus autem cultusque corporis, omnibus pueris in metu et sub cura magistri agentibus, par est. Nec vero vestitum sive calceos mutant, nisi aut omnino conscissis prioribus, aut longi temporis usu consumptis. Nihil autem inter se mercantur aut vendunt ; sed egenti quisque quod habet præbens, refert ab eo quod ipse non habet ; quamvis etiam sine permutatione cunctis libera sit facultas, a quibus libuerit, accipiendi quod opus sit. |

They possess no one particular city but many shift their residence to individual ones. When adherents arrive from elsewhere, all local resources are put at their disposal as if they were their own, and men they have never seen before entertain them like old friends. And so when they travel they carry no baggage at all, but only weapons to keep off bandits. In every town one of the order is appointed specially to look after strangers and issue clothing and provisions. Their dress and personal appearance are like those of children in the fear and care of a tutor. Neither garments nor shoes are changed till they are dropping to pieces or worn out with age. Among themselves nothing is bought or sold: everyone gives what he has to anybody in need and receives from him in return something he himself can use; and even without giving anything in return everyone is free to share the possessions of anyone he chooses. |

| 5 |

| Præcipue circa Deum religiosi sunt. Namque ante solis ortum nihil profani loquuntur, sed ei patria quædam voto celebrant, quasi ut oriatur precantes. Deinde ad quas venerunt singuli artes, a curatoribus dimittuntur. Quumque ad horam quintam studiose fuerint operati, rursus in unum congregantur ; linteisque præcincti velaminibus, ita corpus aquis frigidis abluunt. Atque, hac lustratione facta, in eadem secreta coeunt quo neminem alterius sectæ hominem spirare concessum est, ipsique purificati, velut in sanctum quoddam templum in cenaculum veniunt ; quibus ibi cum silentio residentibus, pistor quidem panes ordine, unum autem vasculum ex uno pulmento singulis cocus apponit. Deinde voce cibum sacerdos antevenit ; neque gustare quemquam fas est, nisi prius Deo celebretur oratio. Post finem quoque prandii vota repetunt. Nam et quum incipiunt, et quum desinunt, quasi datorem vīctus, Deum laudibus canunt. Tunc veluti sacris illis depositis vestimentis, in opere usque ad vesperam versantur. Similiterque inde reversi cenant, consedentibus etiam hospitibus si quos forte intervenisse repererint. Neque vero clamor unquam tectum illud, neque tumultus inquietat, quum etiam loquendi ordine aliis alii cedant, eorumque silentium, extra tectum constitutis arcanum quoddam videatur venerabile. Cujus quidem rei perpetua sobrietas causa est, quodque apud eos edendi aut potandi modus saturitate definitur. |

They are particularly strict in religious observance toward God. Before sunrise they do not utter a word on secular affairs, but offer to Him some traditional rites in prayer as if beseeching Him to appear. After this their supervisors send every man to his particular skill, and they work assiduously till an hour before noon, when they again meet in one place and, donning linen loincloths, wash all over with cold water. After this purification they assemble in secluded areas of their own which no one outside their community is allowed to enter; they then go into the refectory in a state of ritual cleanliness as if it were a holy temple and sit down in silence. Then the baker gives them their loaves in turn, and the cook sets before each man one bowl of one and the same food. The priest says grace before meals: to taste the food before this prayer is forbidden. After breakfast he offers a second prayer; for at beginning and end they give thanks to God as the Giver of life. Then, removing their garments as sacred, they go back to their work till evening. Returning once more, they take supper in the same way, seating their guests beside them if any have arrived. Neither shouting nor disorder ever desecrates the house: in conversation each gives way to his neighbor in turn. To people outside the silence within seems like some awesome mystery; it is the natural result of their unfailing sobriety and the restriction of their food and drink to simple sufficiency. |

| 6 |

| Sed quamvis aliarum rerum nihil sine præcepto faciunt curatoris, tamen in his duobus, hoc est juvando et miserendo, sui juris sunt. Nam et subvenire dignis, quum opus est, suo arbitrio cuique licet, et indigentibus alimenta porrigere. Sane cognatis dare aliquid sine curatoribus, interdictum. Iidem iracundiæ moderatores justi sunt, indignationem cohibent, fidem tuentur, paci obsecundant ; et omne quod dixerint, jurejurando fortius habent. Ipsum autem jusjurandum quasi perjurio deterius vitant. Jam enim mendacii condemnatum arbitrantur, cui sine Deo non creditur. Summum autem studium veterum Scriptis adhibent, ea maxime inde quæ animæ et corpori expediant eligentes. Hinc illis morborum remedia, stirpes medicæ quamque vim propriam singuli lapides habeant, rimantibus conquiruntur. |

In general they take no action without orders from the superiors, but two things are left entirely to them: personal aid and charity. They may of their own accord help any deserving person in need or supply the penniless with food. But gifts to their own kinsfolk require official sanction. Showing indignation only when justified, they keep their tempers under control; they champion good faith and serve the cause of peace. Every word they speak is more binding than an oath; they reject swearing as something worse than perjury, for they say a man is already condemned if he cannot be believed without God being invoked. They are wonderfully devoted to the work of ancient writers, choosing mostly books that can help soul and body; by searching through them they thereby learn all about remedies for disease, medicinal roots and the special properties of individual stones. |

| 7 |

| Sectæ vero suæ studiosis non statim cum eis una collectio, sed per annum integrum extrinsecus commoranti cuique, eundem vīctus ordinem tribuunt, dolabellam quoque, et quod prædictum est perizoma, et albam vestem tradentes. Quum vero processu temporis experimentum continentiæ dederit, accedit etiam ad communem cibum, et purioribus, ob castificationem scilicet, aquis participat ; neque tamen in convictum assumitur. Post ostensionem quippe continentiæ, duobus annis aliis mores ejus probantur. Quumque dignus apparuerit, tunc demum in consortium assumitur. Prius vero quam incipiat communem habere cibum, magnis exsecrationibus adjurat se primum quidem colere Deum, deinceps quoque erga homines servare justitiam, et neque propria sponte nocere cuiquam, neque ex præcepto obesse ; quinimmo iniquos omnes odisse, et collaborare semper justitiæ sectatoribus, fidem omnibus servare, maxime vero principibus. Neque enim absque voluntate Dei cuiquam posse principatus potentiam contingere. Si vero ipse ceteris præsit, nunquam se abusurum viribus potestatis ad contumeliam subjectorum, sed neque veste aut ambitioso aliquo ornatu reliquis eminere, veritatem semper diligere, et habere propositum convincere mentientes. Manus vero a furto, et animam puram servare ab injustis compendiis ; et neque aliquid de mysteriis consectaneos celare, neque profanis eorum quippiam publicare, etiam si intentata quispiam morte compellat. Super hæc autem addunt, nihil se de dogmatibus aliud quam ipsi susceperint, tradere. Fugere autem latrocinia, et conservatum ire simul et dogmatis sui libros et angelorum nomina. His quidem exsecrationibus explorant, et quasi præmuniunt accedentes. |

Persons desirous of joining the sect are not immediately admitted. For a whole year a candidate is excluded but is required to observe the same rule of life as the members, receiving from them a hatchet, the loincloth mentioned above, and white garments. When he has given proof of his temperance during this period, he joins in the common meal; and shares in the purer waters of sanctification, though not yet admitted to the communal life. After demonstrating his self-control, his morals are tested for two more years, and if he is then seen to be worthy, he is accepted into the society. But before touching the communal food he must swear terrible oaths, first that he will revere God, and secondly that he will deal justly with men, will injure no one either of his own accord or at another’s bidding, will always hate the wicked and cooperate with the good, and will keep faith at all times and with all men — especially with rulers, since all power is conferred by God. If he himself receives power, he will never abuse his authority and never by dress or some ostentatious ornament outshine those under him; he will always love truth and seek to convict liars, will keep his hands from stealing and his soul innocent of unholy gain, and will never hide anything from members of the sect or reveal any of their secrets to others, even if brought by violence to the point of death. He further swears to impart their teaching to no man otherwise than as he himself received it; to take no part in armed robbery, and to preserve both the books of the sect and the names of the angels. Such are the oaths by which they make sure of their converts. |

| 8 |

| Deprehensos vero in peccatis a sua congregatione depellunt ; et qui taliter fuerit condemnatus, miserabili plerumque morte consumitur. Illis quidem sacramentis ac ritibus obligatus, neque capere ab aliis oblatum cibum potest. Herbas vero pecudum more decerpens, et fame exesus per membra corrumpitur. Ob quod etiam plurimos plerumque miserati, extremum spiritum agentes receperunt, sufficientem pro peccatis eorum quæ usque ad mortem adduxerit pœnam luisse censentes. |

Men convicted of major offenses are expelled from the order, and the outcast usually comes to a most miserable end; for, bound as he is by oaths and customs, he cannot share the diet of non-members, so is forced to eat grass like beasts till, his body wasted away by starvation, he dies. Compassion compels them to take many offenders back when at their last gasp, since they feel that men tortured to the point of death have paid a sufficient penalty for their offenses. |

| 9 |

| In judiciis vero sunt diligentissimi atque justissimi. Disceptant autem non minus quam centum in unum coacti ; quod autem his decretum fuerit, immobile manet. Veneratio quoque apud eos, post Deum, magna Legislatoris est, ita ut, si quis eum blasphemaverit, morte damnetur. Senibus vero obœdire et plurium quorumque decreto, probabile arbitrantur officium. Quum simul denique sederint decem, nullus unus novem loquitur invitis. Exspuere quoque in medium eorum, vel in dexteram sui partem, quisque devitat. Sabbatis quoque operationem aliquam contigisse, omnibus Judæis diligentius cavent : neque cibum sibi solum pridie præparant — ne videlicet illo die ignem accendant —, sed neque vas aliquod transponere audent, immo nec alvum purgant. Aliis autem diebus fodientes foveam uno pede altam σκαλίδι, hoc est, illa dolabella quam tradi nuper accedentibus diximus, dimissa veste sese diligentissime contegentes, ne scilicet splendori divino injuriam faciant, in eadem fovea ab onere ventris levantur, ac deinceps terram quam effoderant reducunt ; idque ipsum faciunt in locis secretissimis ; et quum naturalis sit ista purgatio, nihilominus tamen sollemne habent, ut quasi ab immunditia diluantur. |